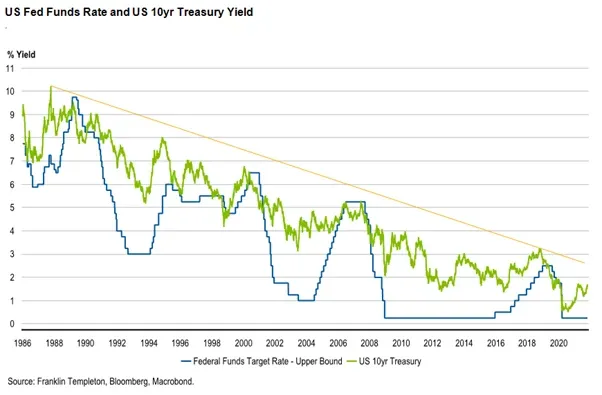

“… is my math basically correct that if there were 100 basis point increase in interest rates, 1% increase in interest rates when we’re looking at a $27 trillion debt, you’re looking at more than a $200 billion a year additional mandatory interest payment … and if you extrapolate that on a 10 year basis … that’d be close to an additional $2 trillion over 10 years of mandatory spending? Is there, Madam Secretary, anything faulty with that analogy or my math?” - Senator Mark Warner September 2021

“I don’t believe there’s anything at all faulty about the math.” - US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen September 2021

A wise analyst once pointed out that there are three prices that ultimately matter for the world. One is the price of oil. Two is the value of the US dollar. And three is the US 10-year treasury yield. These represent:

- the price of energy which everyone relies on

- the price of the world’s reserve currency, and

- the price of borrowing money.

When these prices rise it acts as a constraint on global growth. When they fall conditions improve. The bad news is that energy prices have been rising. Bond yields have been moving higher but are still relatively well behaved. The US dollar has been trending sideways but is well below its pre-pandemic levels.

It’s not hard to reflect on why these can act as headwinds or tailwinds for growth.

1. Oil

In a world that is furiously trying to de-carbonise and shift its energy sources away from fossil fuels, the fact remains that the world is still massively dependent on carbon-based energy sources.

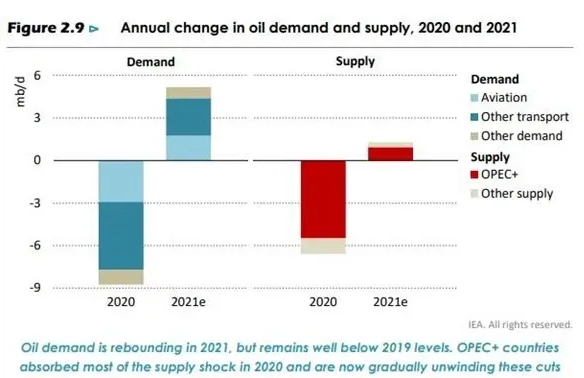

One doesn’t need to be a seasoned commodity analyst to recognise that oil, in particular, is still the lifeblood flowing through the veins of global production. The graph below taken from the International Energy Agency clearly paints a picture of a strong recovery in energy demand since 2020 and a much more limited response in supply in 2021.

Rising energy prices represent a meaningful cost impost on business and consumers and whilst end prices and wages can eventually adjust, these take time. In short, the move acts as a tax on growth at least initially. We recently saw a study highlighting that the lowest 30% of US Income earners spend approximately 15% of after-tax income on energy (gasoline and heating costs).

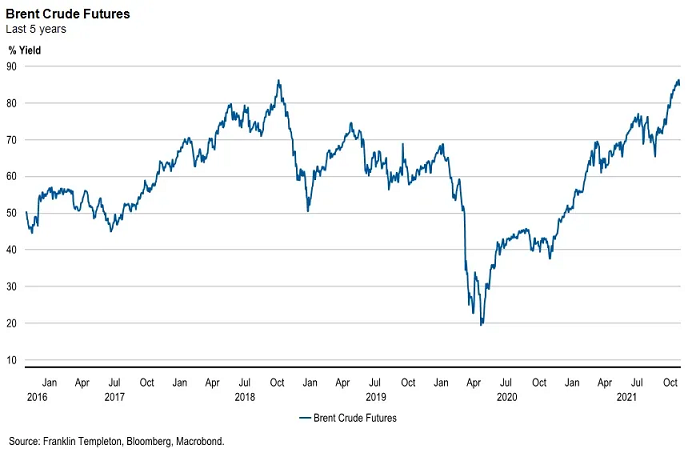

Brent crude is up more than 20% in 2 months and at the highest level in 7 years.

Natural gas prices are up more than 80% this year and, granted are off their recent highs, are suggesting a perfect storm for gas dependent regions such as Europe going into winter where low storage levels and dwindling swing supply sources are exacerbating the problem.

Energy prices are flashing red at the moment. They’re not a positive sign of strong demand so much as a function of insufficient supply as the post-COVID opening progresses. Indeed, activity leading indicators continue to soften led by China, reminding us that this is not your garden variety recovery.

2. The big dollar

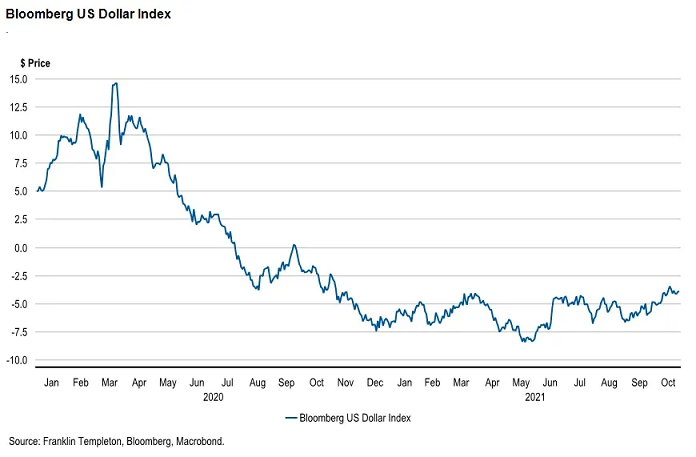

The value of the US dollar matters because the world is short the currency that it requires to do business. Indeed oil, like other commodities, is transacted in US dollars. In addition, the global stock of debt denominated in USD is gargantuan, continues to grow and so any increase in the USD acts to tighten financial conditions. Emerging markets with current account deficits are particularly vulnerable to a stronger USD but in general the world doesn’t work well with the big dollar surging.

The good news is the US dollar has risen but is still well off the highs of levels in 2018/19. Were the US dollar to start to appreciate, alongside higher commodity prices we would worry even more than we currently do. In fact, the Bloomberg US Dollar Index which measures the US dollars against key currencies is well below its pre-pandemic levels.

3. US 10-year yields

The third price that matters is the yield on the US 10-year treasury bond. It matters because no other interest rate forms the basis of present value discounting models of the world’s assets. No other rate is more significant in setting the benchmark for term funding for the world. The higher it goes, the more vulnerable asset prices become. Moreover, in a world drowning in debt, the higher nominal yields rise, the more nominal income has to rise just to preserve debt serviceability. And of course, the USD is not only the world’s most used currency but the world’s most borrowed-in currency. Just ask central bankers across the emerging world how they feel about a rising USD.

Although yields have adjusted higher, they of course are so far somewhat contained and just below highs seen in Q1 2021. In a longer-term context, they remain low. Where we expect they stay.

The post COVID world is limping out of the pandemic with record levels of debt. Consider the following:

- BIS data shows that in 2007 Debt/GDP in all Emerging Economies was 124%. In 1Q 2021 it was 236%.

- Advanced economy debt/GDP has gone from 242% to 309% over this period.

- In case you wonder why Europe’s negative interest rates are probably here as long as the European Union remains in existence, France’s debt/GDP has increased from 223% to 371%!

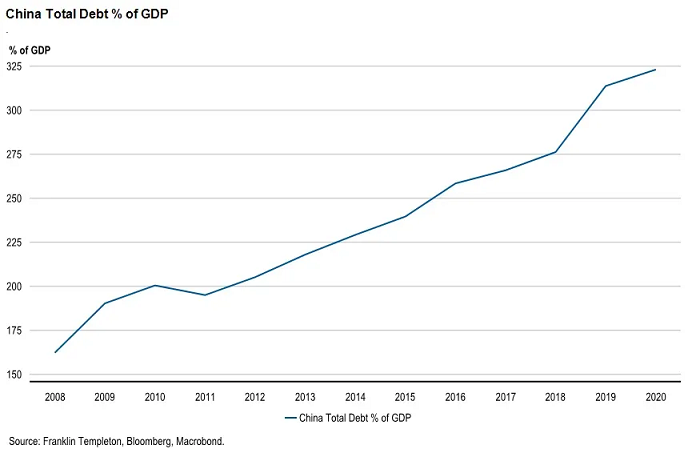

- Perhaps most worryingly of all, China’s total debt-to-GDP ratio has doubled from ~160% of GDP in 2008 to 322% of GDP by 1Q 2021. The most rapidly growing, reliable source of global growth post GFC did so on a credit binge that is now of course being rapidly reined in.

With interest rates still relatively low, the US 10 year is signaling that all is well for the moment. Your writer found it utterly astonishing recently that the current US Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, when asked about the surging level of US government debt as part of a testimony to the US Senate responded that it wasn’t a concern given the low level of interest rates.

That sounds remarkably like a sales pitch to a sub-prime mortgage borrower that a short term artificially low teaser rate is a good measure of long-term home loan affordability. If only the US Treasury adopted APRA’s approach of requiring Australian lenders to stress would-be home loan borrowers by adding 3% to the proposed interest rate.

At the moment, markets aren’t buying into the media-driven inflation hyperbole which continues to be dominated by click-bait around shortages here and there which look to be easing slowly. If they were to, we would see expectations for higher interest rates surge which could drive 10-year yields higher and certainly strengthen the US dollar as the likelihood of the Federal Reserve lifting rates aggressively was priced.

A stronger USD driving borrowing costs higher at a time when the world is once again short oil and energy products would be disastrous for the uneven, unconvincing highly indebted post-COVID recovery.

For now, one out of three is manageable.

Andrew Canobi is a Director, Fixed Income; Joshua Rout, CFA, is a Portfolio Manager and Research Analyst, Fixed Income; and Chris Siniakov is Managing Director, Fixed Income at Franklin Templeton, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment or financial product advice. It does not consider the individual circumstances, objectives, financial situation, or needs of any individual.

For more articles and papers from Franklin Templeton and specialist investment managers, please click here.