The Weekend Edition includes a market update plus Morningstar adds links to two additional articles.

This is the last edition of Firstlinks for 2024. We'll have a week's break and be back on January 2.

To our readers, I'd like to wish you a safe and merry Christmas and New Year. Thank you for all the support that you've given us.

I'd like to give a shout-out to Leisa Bell and Joseph Taylor for their work on Firstlinks, as well as to Morningstar for its support during the year.

Onwards and upwards in 2025.

----

Australia is at a crossroads. For most of our history, we’ve been one of the world’s wealthiest countries. Yet, that wealth has stagnated over the past decade.

There’s been a lot of talk in economic circles about lifting productivity growth. Economists seem to agree that what’s needed is further deregulation of the economy. Much of the debate seems narrow and simplistic, and based as much on politics as economics ie. if you slant right wing in politics, you support deregulation, and if you’re left of centre, you don’t.

The study of history and why some nations prosper and others don’t, provides a broader perspective on the topic. Jarred Diamond’s best seller in the late 1990s, Guns, Germs, and Steel, suggests that geography and the environment shape our societies and prosperity. Daron Acemoglu, who recently won a Nobel Prize in Economics, argues differently, emphasizing the quality of political and economic institutions in driving economic success.

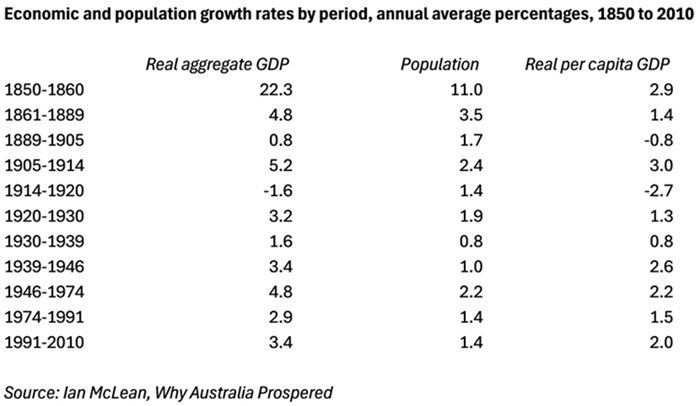

The late Australian economic academic, Ian McLean, put forward a more nuanced thesis in his 2013 book, Why Australia Prospered. McLean’s book is the subject of this article as I think it provides the best clues for how Australia became one of the world’s richest countries, and what we need to do to grow wealth from here.

How we quickly become wealthy

Most Australians are unaware of how lucky we’ve been throughout our short history as a country. Founded in 1788, Australia already obtained the world’s highest incomes by the mid-1800s. And we’ve retained our mantle as one of the richest countries ever since.

Many other nations haven’t been so fortunate. Some have never been wealthy. Others were rich, then became poor. Witness Argentina, which was one of the wealthiest countries in the early 1900s but has declined, ravaged by rolling economic crises for the past 50 years, with high inflation and unemployment, increasing poverty, and political instability.

Australia has managed to maintain its standard of living over a long period. How have we done it?

Key factors behind Australia’s enviable record of prosperity

McLean offers several factors behind our economic success. The first is obvious: our resource base. Yet, it isn’t so obvious, is it? That’s because most of us have heard of the ‘resources curse’ – that an abundance of resources is more a curse than blessing, and typically associated with corruption, low growth, and even failed states.

Australia offers compelling evidence to the contrary. Our farmland and minerals have been the backbone of our economy. In our early history, resources dominated the economy and was a central source of employment. Australia’s exports have long been monopolized by resource-intensive products, beginning with wool and gold. Still today, most of our exports come from primary products.

Another factor behind our wealth is the quality of our institutions, according to McLean. He says institutional flexibility has been critical. What he means by this is that our political and economic institutions have adapted and changed when they haven’t been working to grow our economy.

Examples from the 19th century include the transportation of convicts, the monopolization of grazing land by squatters, and the employment of immigrant, indentured labor on sugar plantations. A more recent example is the reform of labor market institutions by the Hawke Government.

McLean says institutional adaptability a critical factor:

“The capacity of a society to adapt its institutional arrangements in the face of changed economic conditions, or evidence of the adverse consequences for prosperity of doing nothing, is a key factor explaining why there is such a wide range of income levels across countries.”

McLean also emphasizes the importance of political institutions in Australia’s growth. He says Australia benefited greatly from ties to Britain. Early on, we had privileged access to foreign capital and trade, thanks to our colonial ruler.

Also, self-government came early to five of the six colonies in the 1850s. This paved the way for a federal constitution unifying the colonies by 1901. This served us well economically.

McLean’s final point on the importance of institutions highlights the significance of how institutions interacted with our resource abundance. That is, the quality of our institutions has helped us avoid the dreaded resources curse.

Another factor that McLean says is central to our economic success is how policymakers have responded to the major economic shocks, both positive and negative, through our history.

For example, Australia endured an economic depression in the 1890s. It appeared that our resource-based prosperity had come to an end, and the openness of our economy had heightened our vulnerability to events overseas. We shifted strategy to become less reliant on commodities, building up industry behind rising levels of protectionism over the subsequent 50 years.

McLean attributes luck as another factor behind our prosperity. For example, our convict heritage hasn’t been a source of national pride, though McLean believes it provided an underappreciated role in our early prosperity.

That’s because of the peculiar nature of our labor market back then. Most of the convicts sent to New South Wales were selected to maximise the workforce participation rate among the early colonial population. The convicts were selected by gender, age, and physical condition. Men far outnumbered women, most were in the prime working-age range, and only the healthy were transported. This ‘human capital’ was needed to quickly clear land, build key pieces of infrastructure such as roads and houses, and to produce food. Put simply, the convicts had the profile and skills to provide the building blocks for the economy.

Seeds for future prosperity

McLean’s work offers clues for what Australia needs to do to revitalize itself today. My take is that our current institutions have failed to adapt to economic stagnation. They’ve been happy to ride a once-in-a-century boom in iron ore and coal and haven’t wanted to face a world where the best days for these commodities may be behind them ie. there’s unlikely to be another China-style boom for a long time.

They’ve also been content to subsidise massive investment in non-productive industries such as housing.

The complacency of our institutions has left Australia with limited exposure to so-called future facing industries: AI, robotics, biopharmaceuticals, cloud services etc.

We have an education system that could provide the foundations for leadership in the industries of the future. But we don’t seem to have the ambition to want to change and invest in these industries.

We also have resources, like lithium, which can feed into these industries, and we’ve been late to the party in realizing this.

All is far from lost, though there needs to be a more sophisticated debate about how Australia can be bold and creative, and leverage our resources, both mineral and human, to meet the world’s current and future needs.

Our country’s wealth depends on it.

----

In my article this week, I offer nine lessons from this year, including expensive stocks can always get more expensive, Bitcoin is our tulip mania, follow the smart money, the young are coming with pitchforks on housing, and the importance of staying invested.

James Gruber

Also in this week's edition...

Financial industry icon, Don Stammer, is back with the 43rd edition of the X-factor report. Each year, Don picks the X-factor - a largely unexpected influence that wasn’t thought about when the year began but came from left field to have powerful effects on investment returns. What wins in 2024?

We've hit the halfway point of the 2020s and Ashley Owen gives a scorecheck on the Australian stock market. He says this decade's returns haven't been great versus history, though there's reason to hope for a better second half to the decade.

Four years ago, Orbis introduced its 'bubbles' chart to show how the market had become concentrated in one type of stock and one view of the future - namely 'defensive growth' stocks, especially lockdown beneficiaries such as Netflix and Amazon. Turning to today, and Eric Marais says investors are crowding into the same group of stocks, which may open up investment opportunities for those who think differently.

Regulatory tensions have weighed on the share prices of Australian listed private health insurers. Airlie's Emma Fischer thinks the insurers haven't profited at the expense of the hospitals, and that the Government won't step in with a bailout of these hospitals. If right, she says Medibank Private should benefit, and with continued long-term tailwinds from an ageing population, it offers a compelling investment opportunity.

Little noticed is that the inverse correlation between bonds and stocks has returned as inflation and economic growth moderate. PIMCO's Emmanuel Sharef and Erin Browne believe this broadens the potential for risk-adjusted returns in multi-asset portfolios.

A lot has been written about what makes for a good retirement. Australian anthropologist Shiori Shakuto has studied Japanese seniors and that's led her to a counter-intuitive conclusion about what makes for a great retirement: the secret may be found in how we approach our working years.

Two extra articles from Morningstar this weekend. Simonelle Mody looks at the best and worst performing ASX sectors this year, ASX companies that could benefit from our ageing population, while Joseph Taylor highlights two ASX companies with traits of long-term winners.

Lastly, in this week's whitepaper, Franklin Templeton presents survey findings about the future of investing - for money, asset management, portfolios and advice.

****

Weekend market update

A cooler-than-expected November PCE print helped spur a snappy rebound in US stocks on Friday, though the S&P 500 relinquished roughly half its intraday gains into the bell to settle higher by about 1%. Treasurys enjoyed some modest strength with 2- and 30-year yields each dropping two basis points to 4.3% and 4.72%, respectively, while WTI crude remained just below US$70 a barrel and gold bounced to US$2,623 per ounce. Bitcoin hovered south of US$96,000 and the VIX wrapped up the week at 18 and change, down nearly 10 points from Wednesday’s blow-off top.

From AAP netdesk:

The Australian share market on Friday dropped sharply for a second day to close at its worst level in 100 days and suffer its second-worst weekly performance of the year. The benchmark S&P/ASX200 index on Friday fell 1.24% to 8,067, its lowest close since September 11. The broader All Ordinaries fell 1.16% to 8,317.1. The ASX200 fell 2.76% for the week, its worst performance since mid-April.

Eight of the ASX's 11 sectors finished lower on Friday, with energy, utilities and tech higher.

Consumer discretionary shares were collectively the biggest mover, dropping 2.5% as Wesfarmers fell 5% to a more than one-month low of $69.56. Investors may have been concerned about the Perth-based conglomerate's announcement on Friday that it would sell its Coregas industrial gas manufacturer to a Japanese firm for $770 million.

The big four banks were down significantly for a second day, with CBA falling 3.7% to $150.26, NAB dipping 2.2% to $36.37, ANZ dropping 2.3% to $27.94 and Westpac retreating 1.2% to $31.67.

In the heavyweight mining sector, BHP fell 0.2% to $39.59 and Rio Tinto slipped 0.6% to $116.74 while Fortescue 2% to $18.20.

From Shane Oliver, AMP:

- Shares got hit over the last week as the Fed cut rates again as expected but tilted a bit hawkish in foreshadowing less rate cuts next year than previously expected. Noise around a potential US Government shutdown probably hasn’t helped either. This came at a time when shares were already vulnerable after a surge to record highs left them overvalued, a bit over loved and technically overbought. For the week US shares fell 2%, Eurozone shares fell 2.1%, Japanese shares fell 1.9% and the Chinese share market lost 0.1%. The fall in global shares also weighed on the Australian share market which fell 2.8% over the week, with falls led by resources, financials and retail shares. From their highs earlier this month to their lows US shares fell 3.7%, global shares fell 3.5% and Australian shares fell 5%. Bond yields rose sharply on expectations for less Fed rate cuts which further weighed on share market valuations. Oil, metal and iron ore prices fell on prospects for less US rate cuts and as the $US rose. This also weighed on gold and Bitcoin with the latter falling back below $US100,000. The $A fell back to around $US0.62, but this is mainly a strong $US story.

- Shares remain torn between the negatives of rich valuations, higher bond yields, uncertainties as to how much the Fed will cut rates, uncertainties around Trump and geopolitical risks on the one hand versus the positives of global central banks still being in an easing cycle, goldilocks economic conditions particularly in the US, optimism that Trump will reinvigorate the US economy and prospects for stronger profits ahead in Australia. Of course, over the last week the negatives got the upper hand and shares could still fall a bit further in the short term. However, lower than expected US core PCE inflation data for November suggests that the Fed may have gotten too negative on inflation and our overall assessment remains that the trend in shares is still up, including for Australian shares, but expect a far more volatile and constrained ride over the year ahead.

- Out of interest, the Santa rally normally kicks in around mid-December on the back of festive cheer and new year optimism, the investment of any bonuses, low volumes and no capital raisings at this time of year. Over the last 15 years the period from mid-December to year end has seen an average gain of 0.5% in US shares with shares up in this two-week period 10 years out of 15. In Australia, over the last 15 years the average gain over the last two weeks of December has been 1.1% with shares up 10 years out of 15. Of course, it’s not guaranteed and so far Santa looks to have been absent – or may have come early in November - leaving markets overbought and now giving way to a focus on uncertainties around the impact of Trump’s policies and uncertainty about the Fed and RBA.

Curated by James Gruber and Leisa Bell

Latest updates

PDF version of Firstlinks Newsletter

ASX Listed Bond and Hybrid rate sheet from NAB/nabtrade

Monthly Bond and Hybrid updates from ASX

Listed Investment Company (LIC) Indicative NTA Report from Bell Potter

Plus updates and announcements on the Sponsor Noticeboard on our website