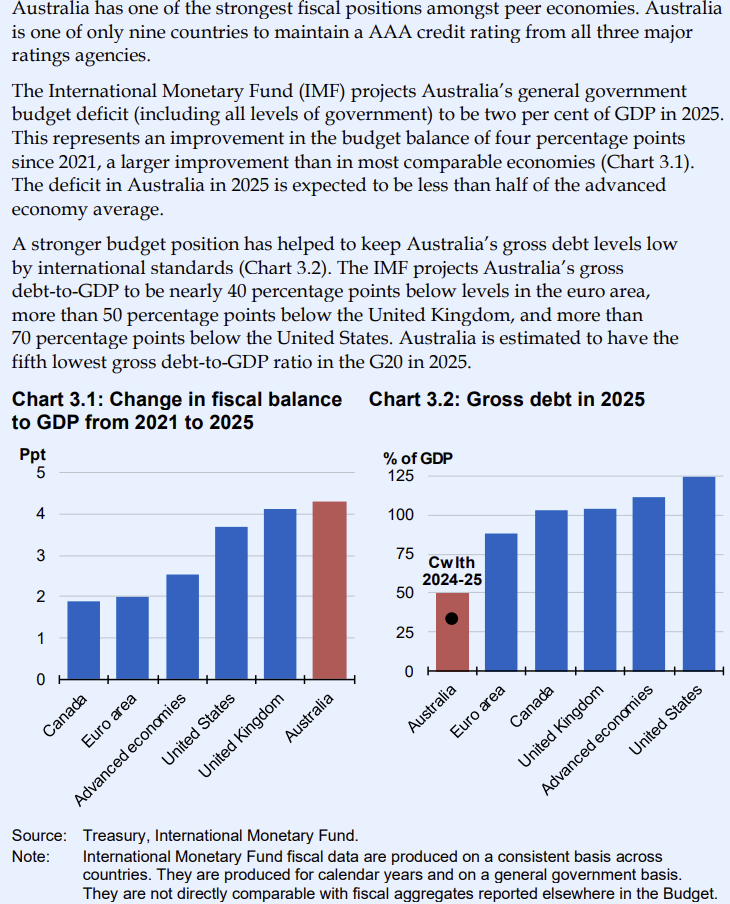

Australia has one of the best fiscal positions in the developed world. Our national debt is relatively low – and that view is before considering our $4 trillion of superannuation savings.

Our national budget outcomes are consistently better than our peers as noted by the International Monetary Fund and highlighted in the budget papers.

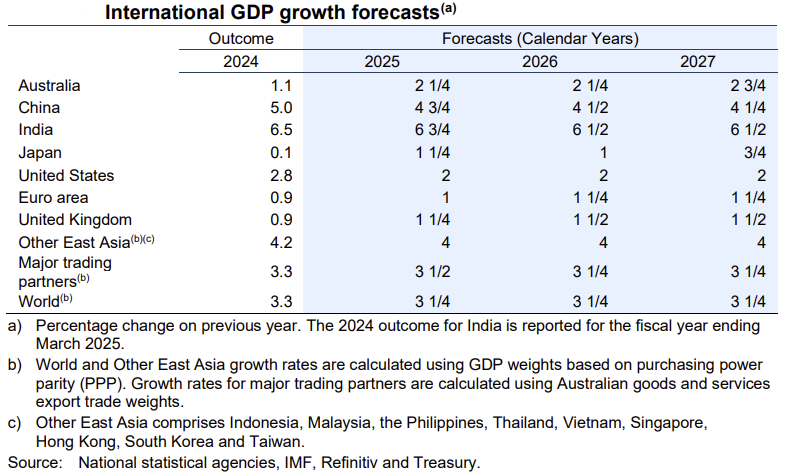

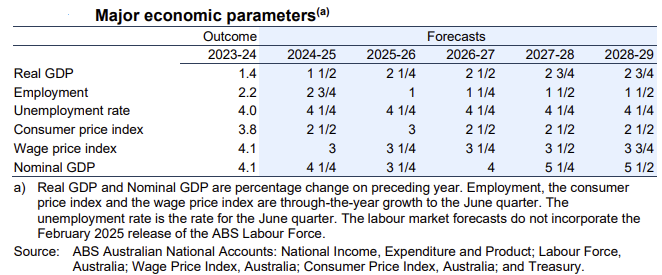

In the recent budget, Treasury economic forecasts, which are the basis of budget outcome predictions, paint a fairly positive outlook. Treasury forecasts (see below) that growth in Australia’s real GDP will be higher than the US in each of the next three years. But are they believable?

How should we approach the economic forecasts presented in the budget?

There have been too many poor forecasts made in budgets in the years since Covid. The most significant was that Government revenue (or taxation collections) was greatly underestimated in the FY22 budget forward projections. This showed up as surprising large fiscal surpluses in FY23 and FY24.

Normally budgets are delivered in May with greater confidence levels after careful analysis of actual trends. The recent budget for FY26 was unexpected and probably rushed.

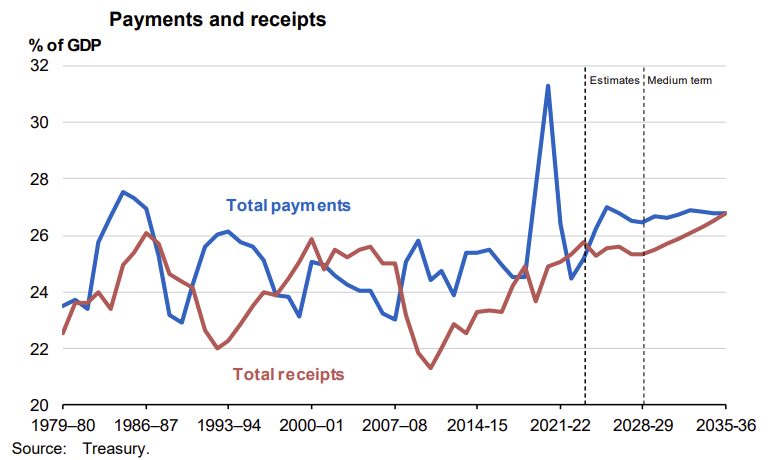

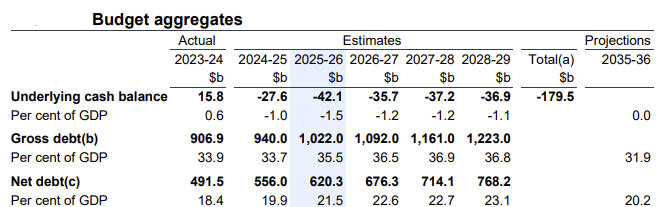

Thus, the level of confidence of forecasts regarding FY26 is lower than normal and forecasts that look further out in time must also be approached with great caution. The following chart looks impressive with the budget moving back to balance in around 2035. However, there is no basis for this forecast, and it represents mere speculation at this stage.

I suspect that the FY26 budget will be subjected to significant adjustments post election - no matter who forms the next Government.

The budget, the economy, pre and post Covid

We can assess our economic performance as we would for an operating business prior to and after the Covid crisis. Such an analysis considers and compares relative performance in relatively 'stable or normal' periods, unaffected by a “once in a century health crisis”.

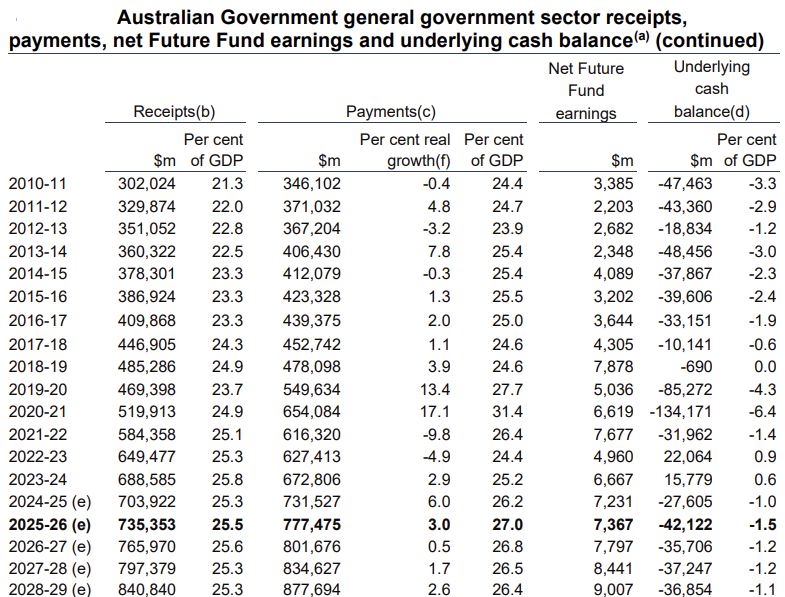

The next table, found deep in the budget papers, is instructive. From it, we can both draw some important observations and conclusions.

The important periods to consider and compare are the two budgets of FY18 and FY19 (actual pre-Covid), with the FY25 budget (forecast current year) and the FY26 budget (forecast).

The pre-Covid economy and budget outcomes

From the above table, we can calculate the following:

- FY18 Australian GDP was $1.83 trillion and the budget cash deficit was 0.56% of GDP.

- FY19 Australian GDP was $1.95 trillion with a nominal budget cash deficit measured against GDP. Yes, we had a near balanced budget in FY19.

In the two years commencing 30 June 2017 and ending 30 June 2019, the Australian economy grew by $190 billion representing 10.8% over two years (or by 5.4% per annum).

Inflation was below 2% and so real annual growth approximated 3% per annum. The economy grew, not greatly stimulated by fiscal policy as budget outcomes were fairly neutral.

Compared to pre-Covid, how is our economy and the budget projected to perform?

FY25 and FY26 forecasts

Again, from the above table we can calculate the following:

- FY25 Australian GDP is expected to reach $2.78 trillion. The budget cash deficit is forecast at about 1% of GDP.

- FY26 Australian GDP is forecast to be $2.90 trillion (gross GDP growth of 4.3%) with a cash deficit of 1.5% of GDP.

Adjusting for forecast inflation the real growth is 1.8%. Given the rising budget cash deficit, the multiplier of the fiscal deficit (stimulative) to growth is low and is declining.

Australia’s real growth has slowed and will slow further compared to the pre-Covid years.

In the two years ending in June 2026, it is forecast that our economy will grow by $230 billion representing 8.6% over two years (or by 4.3% per annum). With inflation averaging 2.75%, Australia’s real growth will slow to 1.6% per annum over this period.

Our economy has grown by $900 billion in seven years

The actual total growth of the Australian economy, including inflation, has been significant from 2017 to 2024. The economy grew by an extraordinary $900 billion or 51%, suggesting an annual growth rate of 7%!

However, there are clear reasons for this growth.

First, the surge in economic growth was substantially supported by the $250 billion of budget cash deficits recorded over FY20, FY21 and FY22. These deficits (averaging 4% of GDP) were in response to the Covid shutdowns.

Second, the growth surge was also greatly supported by inflation of 8% in FY22.

However, over the period, the AUD has devalued sharply with growth measured in USD not as impressive. We have suffered an annual average currency depreciation of about 2% per annum over the last seven years.

The growth was also supported by extraordinary monetary policies. Remember QE, unlimited funding to banks and near zero interest rates.

It was the largesse of both fiscal and monetary policies that created a ballooning Australian economy. A lot of air with not as much substance.

'A bloated economy'

Australia’s real economic growth has become anemic over the last two years when the effects of both elevated inflation and massive Covid fiscal stimulus are properly considered.

Further, real income growth has slowed dramatically post-Covid. In per capita terms, noting the immigration surge and resultant population growth, real income growth of the average Australian household has declined. Wages growth and household income has not matched inflation. The cost-of-living surge has bitten average Australians. The legacy of this must be considered in economic forecasting but Treasury assumes that it will be rectified without explanation or based on a clear policy.

As noted above the size of the Australian economy has ballooned in size. It now presents as a bloated economy, dominated by the excessive prices of residential property and related household debt. The size of the public sector has ballooned.

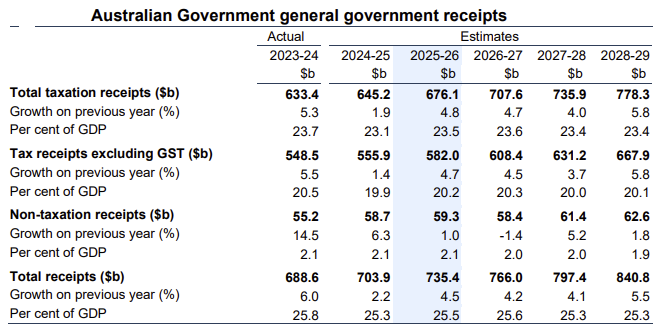

Considering budget receipts, the Government will collect $735 billion in FY26 or $300 billion more than they did in FY17. The budget has grown faster than the economy – 80% growth in budget outcomes compared to 50% growth in the economy.

This growth in the budget has been excessively funded by personal or direct taxation.

Arguably fiscal waste has developed given that the national economy has grown at a slower rate than budget expenditure. Inefficient public services and a national productivity decline is the result. Australia is now an expensive place to live.

Asset prices and the 'cost of doing business' have also surged at rates well above inflation readings. Without a clearly defined national growth plan, that includes an energy cost solution, business confidence remains weak, and Treasury has no real basis for forecasting the point at which it recovers.

Unfortunately, neither the bureaucracy or our political leaders have plans to address either the cost of living, the unaffordability of housing, the cost of doing business or declining productivity. There is no discussion of a taxation review.

The budget papers struggle to acknowledge that there are even problems to address.

The budget’s rosy forecasts

The forecasts above suggest a fairly solid recovery in the economy in FY26 following the low growth of FY24 and FY25.

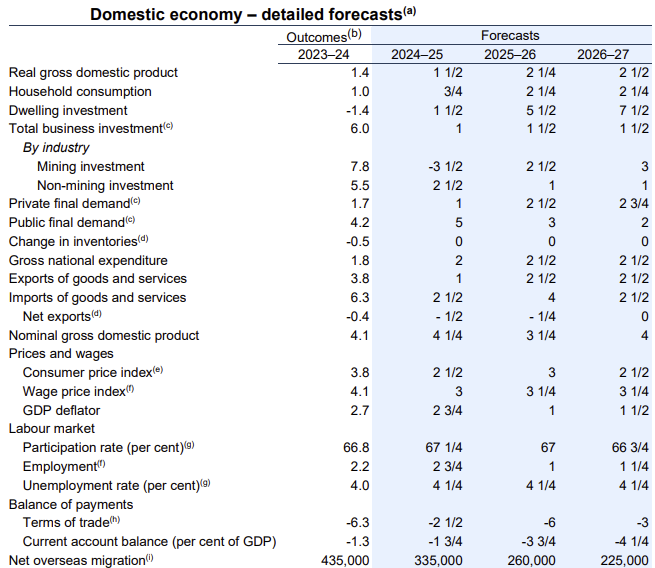

More detailed forecasting appears in the next table.

What can we glean from these forecasts?

- Household consumption is forecast to lift dramatically in FY26 over FY25 but for no apparent reason;

- Non mining business investment growth is expected to slow – i.e. a real decline investment, below inflation, is projected.

- It is that private demand will replace public demand to sustain economic activity and growth.

- It is forecast that inflation will drift higher in FY26 before declining again in FY27 to stay inside the RBAs inflation band;

- The unemployment rate will remain steady even as participation rates decline;

- Australia’s terms of trade will decline (noting this forecast has been over the last 5 years) which will cause a sharp deterioration in our external capital account; and

- Net migration will fall but there will still be 800,000 immigrants arriving through FY25 to FY27.

Treasury assumptions or predictions regarding economic growth (to improve against our peers), immigration (to moderately decline), inflation (to drift lower), taxation rate adjustments (unknown), currency (remain constant) and commodity prices (to weaken) are created but without conviction.

The next table tracks taxation receipts, and it discloses a marked and unexplained deterioration in forecast tax collections in FY25 compared to the mid year budget update.

PAYG taxation receipts are forecast to grow at a very low rate (1.4%). With employment growth remaining buoyant and real wage rises flowing, it suggests that the tax cuts of 1 July 2024 have suddenly (and belatedly) had an effect.

Australia’s Government debt – is it really a concern?

As noted above the IMF and all rating agencies have far less concern with Australia’s financial position then the plethora of commentators across our local media.

Australia has far less Government debt then most of our closest peers. Our real problem is with household debt, but from a national perspective this is balanced by our extraordinarily large superannuation assets.

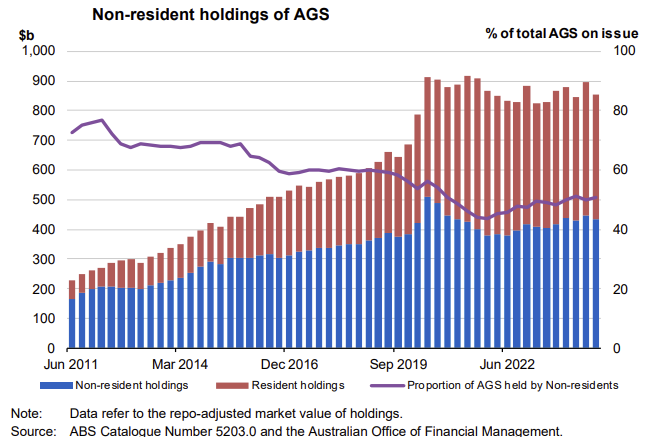

Australia’s AAA Government debt is relatively small in size and it remains a highly attractive place for foreigners to invest. The budget revealed that once again over 50% of our Government debt is owned by non residents.

Arguably a more thoughtful policy response, that directs Australian super funds to own Australian bonds, would be greatly beneficial to our capital account and support the AUD. It would also protect Australian in the event of a financial calamity that caused foreigners to flee our bonds. A mere 20% allocation to Australian bonds by Australian super funds would fully cover our Government debt.

Australia has abundant capital to fund our growth but will do not have policies that are focussed on growth or on connecting our savings capital with opportunity.

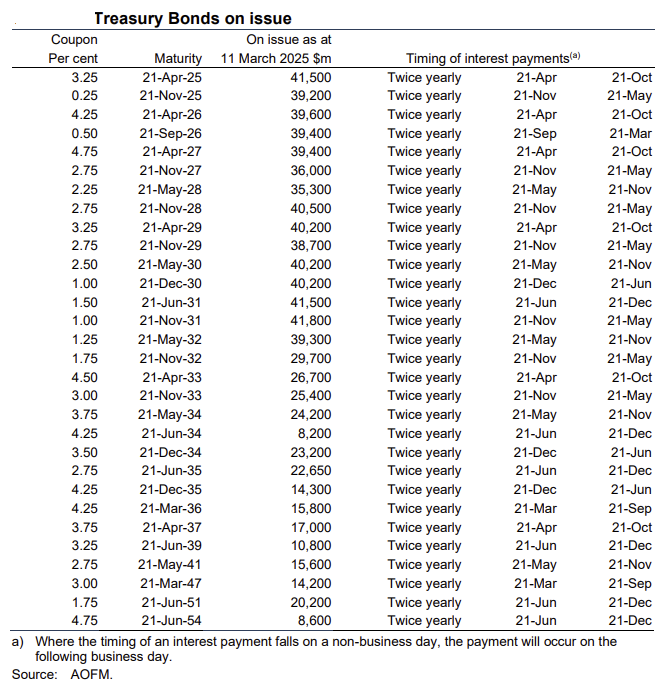

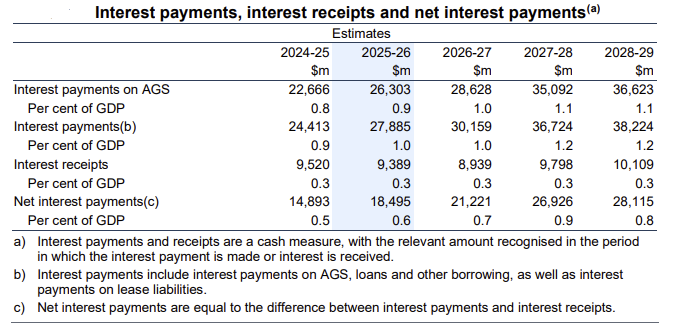

As the next table discloses, the rolling of $160 billion of Commonwealth bonds, some issued during Covid, could be well covered by Australia superannuation funds that are increasingly defaulting into offshore markets.

The rolling of bonds, issued at historically low yields, during the Covid crisis, will lead to a solid jump in interest payments flowing through the budget. This is one budget forecast that we can rely upon. The interest bill for the Australian Government will continue to rise but not from excessive debt, but from the resetting of pre-Covid interest rates.

The FY26 budget – forecast growth that is unprosperous

The FY26 budget is a rushed document full of dubious forecasts. A comparison of Australia’s budget and economic outcomes prior to Covid, with those presented in the FY26 budget Papers, exhibits a sharp decline in the quality of the budget forecasting. Further, the economic returns from budget expenditures measured in real economic activity, is on a declining trend along with productivity.

The economy, budget and Government debt were in good shape pre-Covid – but is arguable that we as a nation have lost our way during and straight after Covid. The inability to reset an economic growth agenda since Covid, that covers targets for energy, housing, health, aged care and defence, is starkly on display in the budget papers. There appears to be very limited appetite for any significant tax reform, structural planning, or a reduction of red or green tape. Comprehensive policy addressing the cost of living and the cost of doing business does not exist.

There is no report card as to how we are going against plan because there is no plan. As a nation we should be all be concerned by the lack of a national vision that threatens to continue to deliver more unprosperous economic growth.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.