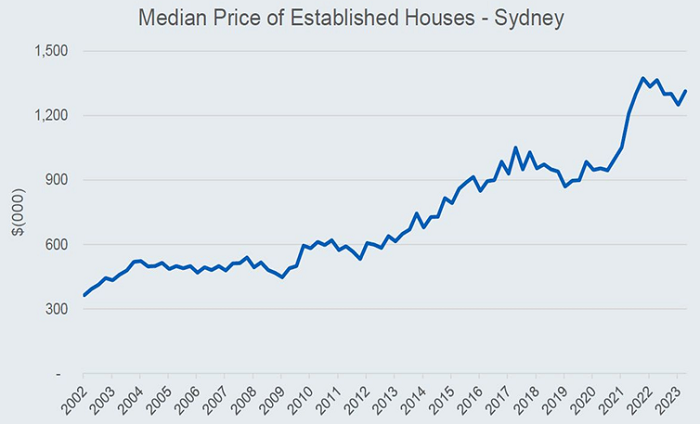

It seems all of us have heard comments like “house prices always go up”. Anyone with a basic understanding of maths and economics have told those people they cannot be correct. With that, let’s look at the median house price in Sydney since 2002:

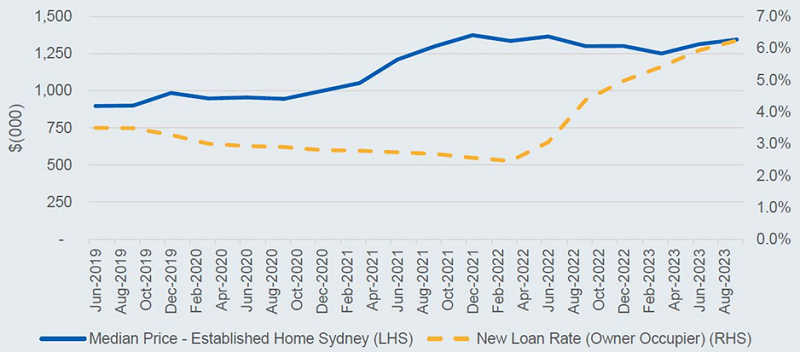

Looking at the chart above it almost does seem like house prices always go up. But wait: what happens when interest rates go up, surely house prices will crash? Let’s zoom into the chart above and look at the effect of recent interest rate rises on the value of homes in Sydney:

Despite interest rates on new home loans more than doubling off their lows, it is clear that house prices have been stunningly resilient, growing once more after marginally decreasing when rates began to increase.

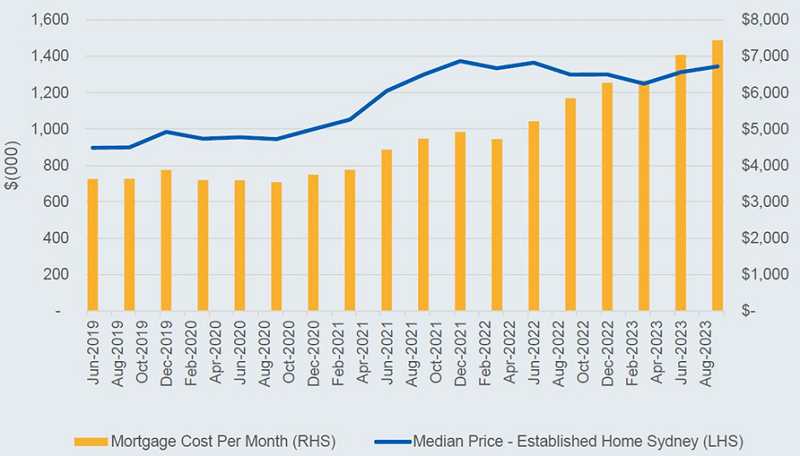

Those concerned about the sustainability of current house prices will correctly point to just how much it costs to own a home. Approximately 75% of home purchases are supported by the use of a mortgage. Obviously, those making the purchase can only do so if they can service the payment on that mortgage. To show this, the chart below looks at the monthly cost of servicing a new mortgage (Loan to Value = 90%) on the median home in Sydney and how it has changed over the same period.

The cost of servicing a mortgage has clearly risen dramatically. A mortgage obtained on the median home in Sydney now costs more than $7,400 per month to service. This has increased by more than 50% since December 2021, less than two years ago. Common sense suggests that this must have a limit. Surely at some point people can’t afford to service their mortgage anymore and surely even the ~25% of people who buy a home with cash won’t have enough cash to buy the home they want. That all has to be true, but house prices prove that at this stage we have not reached that breaking point.

How can we afford this?

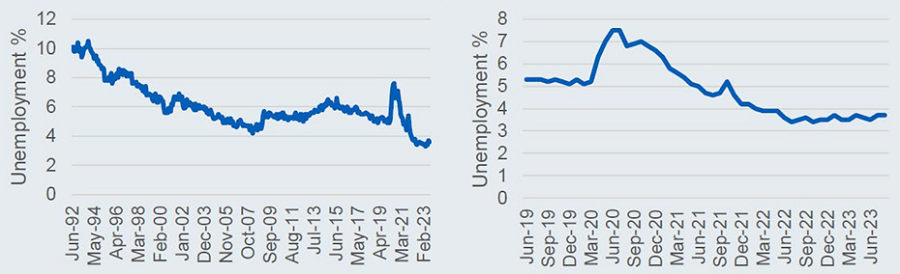

Basic economics states that in a market economy, the price of a good or service is a function of its supply and demand. Housing is no different. The demand for housing should be simple to understand. All Australians have demand for a place to live. To support ‘elevated’ house prices and increased mortgage servicing, there has to be a capacity to pay monthly costs. This capacity is most commonly tied to a person’s income. When entering into a 30-year mortgage, someone’s view of their job security is also front of mind. In this context, a chart of long-term and more recent unemployment rates in Australia is presented below:

As can be seen, unemployment rates are at multi-generational lows, serving to add to demand for housing at ever-increasing prices.

Housing demand

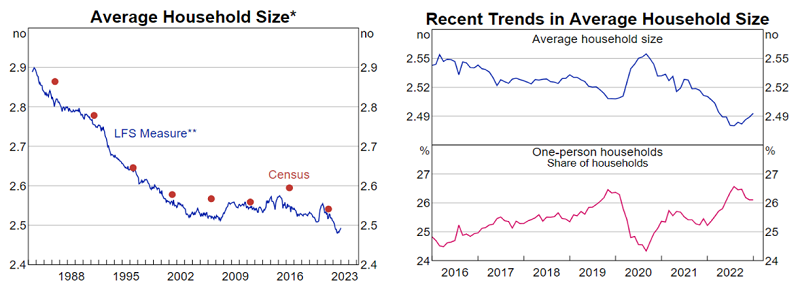

In the most basic sense, the quantum of dwellings needed in Australia is related to the amount of people in each dwelling and the population of the country. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) have compiled the nation’s historic average household size and recent trends as shown below:

While perhaps a controversial figure, former RBA Governor Phillip Lowe summed up recent changes astutely, saying:

“During the pandemic, the average number of people living in each household declined. People wanted more space. They were working from home. Rents actually declined for a while. People said, ‘Rather than have a flatmate I will just have an office at home,’ so the average number of people living in each dwelling declined and that increased the demand as a result for the total number of dwellings”.

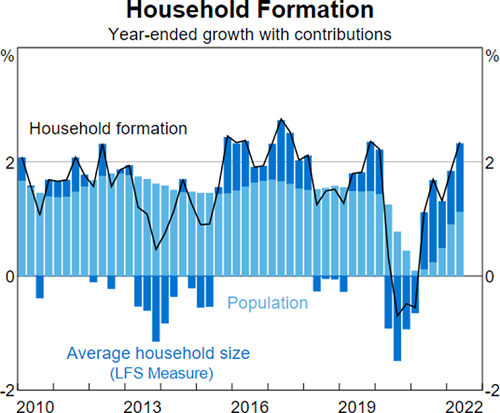

So, we have less people living in each dwelling and the other component of household requirements, population, is also increasing strongly. Again, the RBA and ABS help by showing both the impact of population growth (in light blue) and change in household size (dark blue) over time in the chart below:

Again, Phillip Lowe sums up the situation:

“The other thing that is now happening is a big increase in population. The population is increasing by two per cent this year. Are there two per cent more houses? No. The rate of addition to the housing stock is very low. We have a lot of people coming into the country.”

This comment touches on the other key element to home prices in Australia. Namely, the supply of new property.

Housing supply

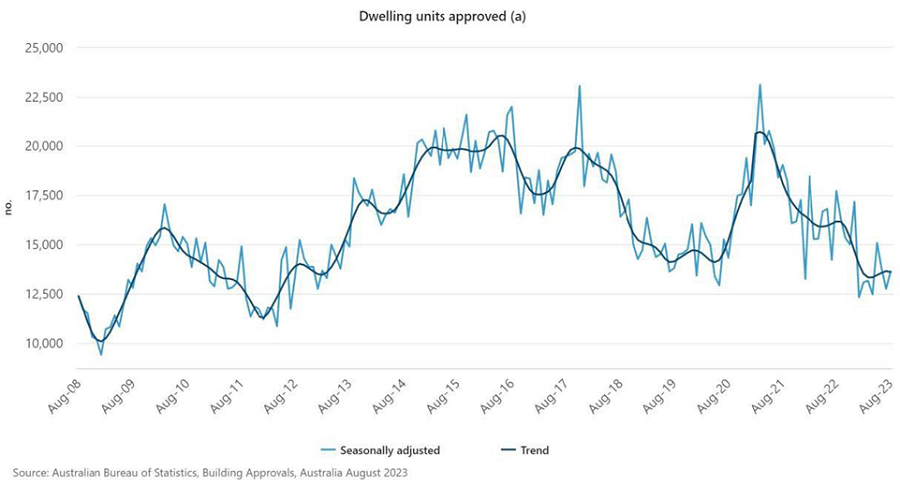

So there clearly is a need to build new houses. Given the voracious demand for residential properties at elevated prices, one would think that residential developers would address this demand and supply the properties the population clearly want. Two major factors are holding back the supply that would otherwise naturally occur.

Firstly, the cost of building new homes is a major factor. A residential property developer will require approximately a 20% profit margin on top of their costs to put new housing supply into the market. The costs of developing that property comprise:

- the cost of the land on which it is built,

- the hard costs of the materials used,

- finance costs,

- architectural and planning costs and

- the cost of labour to physically build the property.

In recent times, all of these costs have been increasing. Materials costs increased significantly with supply chain disruptions during the COVID-affected period and only now is the “rate of growth” slowing. Labour costs are also ever increasing, as even the availability of workers is a significant challenge in many cases (see unemployment rates). Each of these increased costs place downward pressure on the supply of new properties.

The real issue

Arguably the biggest factor limiting new supply however is simply being allowed to build new properties. New building requires a myriad of approvals, principally development approvals, from local councils or state governments. Local constituents tend to be against development in their area, often known as NIMBYs (Not In My Backyard). Local councils and members of parliament are voted in by existing residents of a geographic area and hence are incentivised to block the building of new houses.

To provide one such blatant example, one member of parliament (MP) made the comment: “Housing in Australia is in crisis,” describing the cost of housing forcing “families [to sleep] in their cars”. This same MP has vehemently opposed the development of more than 800 dwellings on an unused site in their electorate. Going further, in an attempt to justify the position, he argued that such development activity “drives up the cost of rent and house prices.” This is demonstrably false and fails to pass even the most basic test of common sense. We are not referencing it to call out an individual, but rather providing an example of just how difficult it is to obtain approval to address the housing supply shortage, even from those aware of the need. To see how dire this supply issue has become, see the chart below, provided by the ABS, showing the trend in approvals for dwelling units despite the obvious need for housing.

What are we doing about it?

Amending the long-held planning practices, incentives of government and fixing global supply chains is above our pay grade. What we can do is observe and acknowledge the situation and make investments that benefit from the realities of housing undersupply. This can be done by investing in companies that either have development approved housing projects, or a history of working with planning authorities to obtain approval, despite all the complexities inherent in residential development.

One such investment in the portfolio is Mirvac Group (MGR). Most of MGR’s development takes place in urban infill locations. These projects often increase density and at times have included iconic projects across Australia. MGR is currently developing the old Channel 9 headquarters in Willoughby in Sydney’s North, which will deliver 417 lots, with a total development value of $800 million. Existing iconic projects completed by MGR include The Melbournian, and The Eastbourne in Melbourne. MGR has also been a pioneer in the embryonic ‘build to rent’ property sector. This involves building large apartment buildings, with all lots held for rent on an ongoing basis as opposed to being sold on completion. Those in Melbourne can inspect LIV Munro, adjacent to Queen Victoria Markets, which was recently completed and has 490 apartments available for rent. In the midst of record low rental vacancy, this business both addresses a need and provides low risk returns to investors.

Another investment in the portfolio is Peet Limited (PPC), which specialises in master planned communities across the country. These tend to be extremely large plots of land on the urban fringe of major cities and will effectively be new suburbs and in some cases almost new cities. PPC’s largest project is Flagstone, located between Brisbane and the Gold Coast in Southeast Queensland. It will take a generation to complete, however once built will house 120,000 people and become Australia’s 20th largest city, a similar scale to Cairns. It will include a 100-hectare town centre, with a regional shopping centre similar in size to Chatswood Chase and will have a bigger town centre than the Brisbane CBD. This project has all relevant approvals. It is projects such as this that will go a small way to addressing Australia’s housing undersupply.

A closing note

The current balance in Australian housing is a bit like an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object. Interest rates are having a meaningful impact on the affordability of housing and clearly are putting downward pressure on housing prices. Fighting against this, ever increasing demand and insufficient supply are supporting home values. Over time, these factors should find an equilibrium. Investing in those who are helping to address this undersupply is prudent both from an investment perspective and for the benefit of the nation.

Stuart Cartledge is Managing Director of Phoenix Portfolios, a boutique investment manager partly owned by staff and partly owned by ASX-listed Cromwell Property Group. Cromwell Funds Management is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is not intended to provide investment or financial advice or to act as any sort of offer or disclosure document. It has been prepared without taking into account any investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Any potential investor should make their own independent enquiries, and talk to their professional advisers, before making investment decisions.

For more articles and papers from Cromwell, please click here.