This is an edited transcript of an interview by Tom Piotrowski of CommSec with Coolabah Capital Investments CIO Christopher Joye.

Tom Piotrowski: There was a point where a significant proportion of the global bond market was negatively yielding. Now, we've seen a rapid increase in rates. I'm interested in the very simple intellectual process that you have in terms of trying to make sense of those moves.

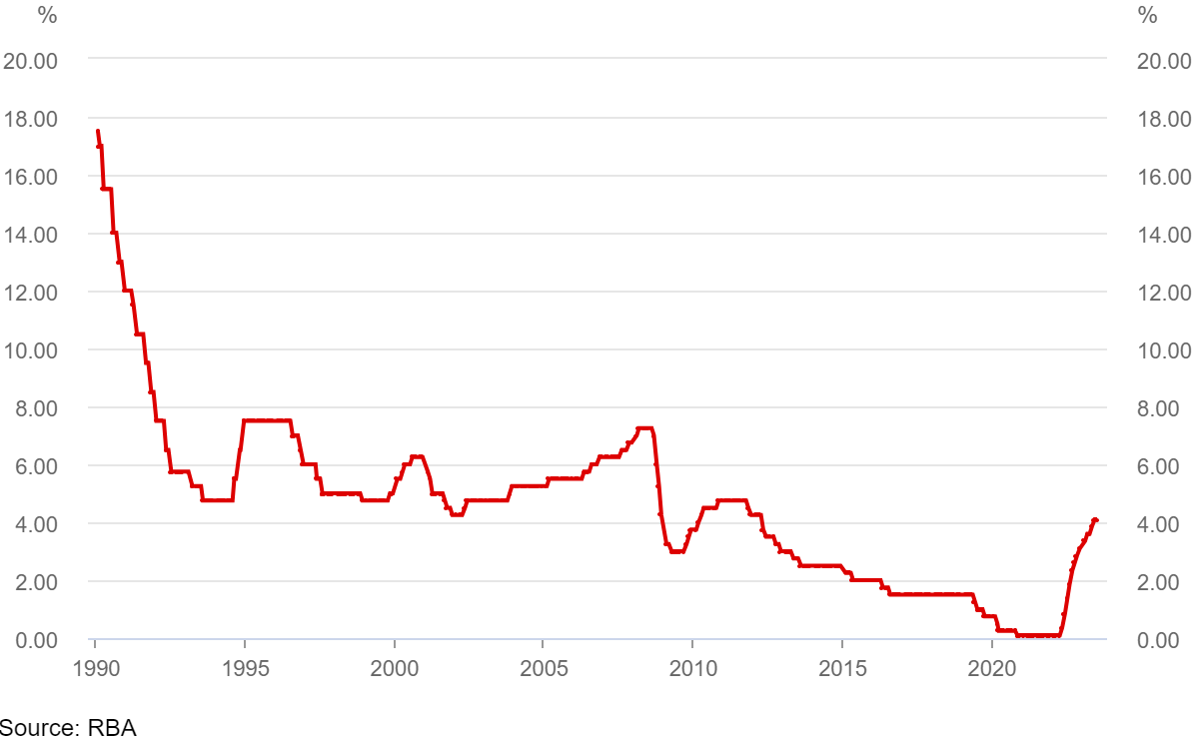

Joye: I think, after the GFC, and really, for the last 30 years, interest rates have come down from circa 17% in 1990 to 0% recently, and that was because we had no inflation. But we always felt that in response to the GFC, we'd get low rates and lots of money printing and the money printing would bid up the value of all assets, and that would inevitably create excess demand and too much inflation. With the pandemic, we threw in a huge supply shock, and the money printing increased with gusto, and rates were even more stimulatory, and we also had governments through fiscal policy give out record amounts of cash.

We had the mother of all supply and demand side inflation storms. We've been faced with the highest inflation rates in 40 years, and late last year, we argued that rates would have to go much, much higher. So, the RBA cash rate was at zero and same in the U.S., and we argued that the Fed would have to lift its cash rate above 3%. And 10-year bond yields issued by governments, which were sitting around 1% late last year, we argued would have to go to north of 3.2%.

Importantly, that would have a few consequences. We forecast that would reduce the value of equities by more than 30%, specifically U.S. equities. We said crypto would crash in December last year. We said in October last year that Aussie house prices would fall by 15% to 25% and that credit spreads would widen.

And that's actually all negative for my asset class, because fixed rate bonds, their price falls when yields rise. And when credit spreads widen, prices also fall. Bond markets had basically their worst year in about 100 years.

And everything that we thought would happen more or less came to pass. The quid pro quo is now we sit in the world with high interest rates, wide credit spreads, and my asset class, which I really strongly disliked – in fact, we put on $10 billion of bond shorts late last year through to mid this year to express that negative view to profit from bond prices falling. But those assets, bonds which looked terrible for a while, suddenly look attractive.

Piotrowski: They look attractive in relative terms given where we've come from. But the question that the markets struggle with is, what's the terminal point at which they stop hiking. What's your thinking?

Joye: Here in Australia, we're at 3.1%. We were at 0.1% last year. And a 300-basis-point increase is the biggest increase more or less ever. When banks were lending home loans to customers in 2020 and 2021, they were offering these super cheap fixed rate deals at circa 2% for three-year or four-year loans. The regulator, APRA, said the banks only need to stress a borrower's capacity to repay by a 2.5% increase in interest rates or a 250-basis-point increase. And the RBA has now increased rates by 300 with more to come.

Piotrowski: Yeah. So, more than redlining.

Joye: We're redlining. To answer your question, the market is saying that the RBA will finish at a cash rate of about 3.7%. Our sense is they may conk out a little bit before then, so maybe low 3s. But we're talking about the difference between two or three meetings.

Make no mistake though, the RBA is absolutely crushing the economy. House prices are falling, consumer confidence is today worse than it was in the GFC, retail spending is nose diving, business confidence has collapsed, and there is a risk the economy will go into recession. And according to the RBA's own numbers, if we get cash to 3.5%, 15% of all borrowers will actually have negative cash loads.

RBA cash rate

What does that mean? The RBA looked at their incomes, and it took off their mortgage repayments and only essential living expenses. And so, 15% are going to basically not have enough money to repay their home loans at a 3.5% cash rate, which is only a few meetings away. So, we think the RBA has probably overdone it. We think the RBA is aping the Fed. The Fed by March should be at 5%. Market is pricing about 4.9%. We think the Fed could go a little bit further, to 5% or 5.5%.

But I think the good news for everybody, if you're long – if you're in housing, commercial property, equities, crypto, bonds – the good news is, those terminal cash rates are very much just around the corner. They're in sight.

The bad news is – and this is super important for people to understand – the different asset classes adjust with different speeds. In my bond portfolio, if the RBA lifts its rate, that day it's reflected in my portfolio, and my yields instantaneously adjust. If we think about house prices, they started falling in May 2022 in response to the hikes. But they will almost certainly fall for another 6 to 12 months. And if you look at commercial property, they've hardly adjusted. So commercial property yields remain incredibly low. You earn more on government bonds and senior ranking bank bonds than you do on commercial property, which makes no sense. Normally, commercial property pays you about 5% above government bonds, and right now, they're paying basically the same yield as government bonds because it's illiquid and it takes time to adjust. Venture capital and private equity – same deal. They will take time to adjust. Equities are liquid, as you know, and our view is that equities have adjusted to much higher interest.

We are forecasting a non-trivial U.S. recession. We're unconvinced that equities are fully pricing in the impact on earnings of not just a U.S. recession, but we think there will be a global recession. The likelihood is, we've never seen such synchronised global interest rate hikes and it's likely to have a big impact on demand.

Piotrowski: You've written that when the U.S. adjusts to an inflation shock, the decline tends to be north of 20% over that period.

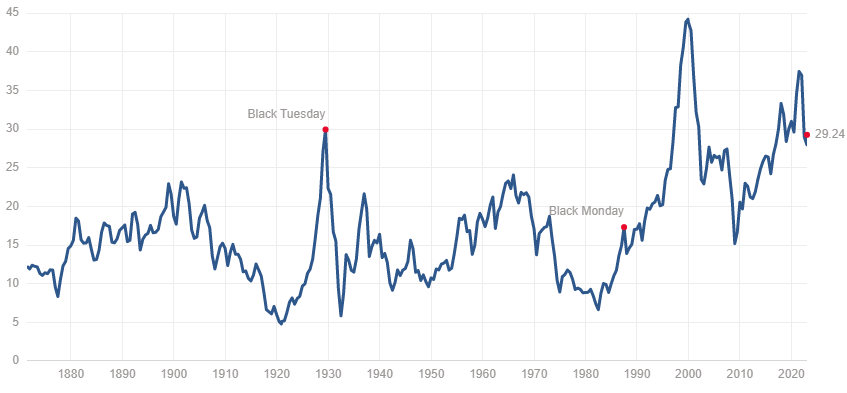

Joye: Robert Shiller, who won the Nobel Prize, produces something called a cyclically-adjusted price earnings (CAPE) multiple that adjusts for the business cycle. So, it's like a longer-term P/E. And the U.S. equity market is a tail that wags the dog. So, when we model equities, we think about the U.S., because everything is going to follow with some sort of correlation or beta. And in December last year, the U.S. equity market had only once in the last 140 years been more overvalued, and that was right at the peak of the tech boom. And we've looked at every time these cyclically-adjusted P/Es get above 30 times, and I think we were at 39 times late last year…

Piotrowski: It's staggering. But then, again, sympathetic to what was happening from a central bank perspective.

Joye: Very sympathetic. But here's the data.

When we look at the CAPE ratios, when it goes above 30 times, in the next decade, equities most of the time give negative returns after adjusting for inflation. There are a few periods where they've given you small positive returns, but the returns are not that flash.

The problem is, we've seen the S&P500, peak to trough at some points has been down as much as 26% and NASDAQ has been down as much as 36%. Equities have adjusted a lot. But the starting point was heinously expensive. The average CAPE is 15 to 16 times. Today, we're still at 29 times. We are still massively expensive compared to history, and I think a lot of that was explained by the idea that rates would remain low for long and also the idea that money would be very cheap for a long time.

Shiller P/E ratio

Source: Robert Shiller

I'm not an equity expert. I am an expert on banks. Hence why we're trading bank stocks. But I think balance of probabilities, the returns from equities if we have a synchronised global recession over the next year, which is our central case, the returns for equities would be very poor.

And I think the existential crisis for all the investors listening to this is this. Bank stocks are paying you, as one example, a fully franked dividend yield at 5%. But I can get almost 5% on a CBA senior bond and I can get 6% on a CBA Tier 2 bond, and I can get about 5.5% on the CBA hybrid. So, these are safer securities, much safer than equity, and they're giving higher yield than equity. And that doesn't make sense. It doesn't make sense for commercial property to pay 4.5% to 5.5%. Across the Aussie equity market, the fully franked dividend yield is about 6%. With government bond yields at 3% to 4% and bank bond yields at 5% to 6%, the yields on everything need to increase, and the way that happens is through much lower prices.

Piotrowski: Are we heading towards anything that's going to look normal in the next little while, given what we've experienced in the last couple of years?

Joye: My view is all the central banks will hike too far. Economies will go into recession. They'll pull back rates, but not to 0.

You'll probably get some sort of modest bounce, but once asset prices, and I mean everything – property, crypto, equities, bonds, et cetera – adjust to the fact that risk-free cash will pay you 3% to 4%, so you'll be able to get term deposits for the foreseeable future paying 3% to 4%, and anything competing against term deposits is going to have to pay much more. Thereafter, I think you're going to see markets driven by income growth not interest rates.

If you think about house prices, all the house price moves really since 2007 have been driven by huge changes in the RBA's cash rate. But once it settles again, I think house prices will track wages. Wages grow at 3% to 4%. House price growth rather than being 7% to 10% is likely to be a lot lower, and I think that's also true of equities and other related assets.

Tom Piotrowski is an economist and market analyst at CommSec. Christopher Joye is Founder, Chief Investment Officer and Portfolio Manager at Coolabah Capital Investments.

This is an edited transcript of an interview in December 2022. Listen to the full version here. Republished with permission.