Introduction

Professor Tim Congdon is Chair of the Institute of International Monetary Research at the University of Buckingham. Firstlinks has featured his work several times, starting at the height of the pandemic on 15 April 2020 in Magic money printing and the reality of inflation, when he said:

"What is wrong with the supposed ‘magic money tree’? The trouble is this. When new money is fabricated ‘out of thin air’ by money printing or the electronic addition of balance sheet entries, the value of that money is not necessarily given for all time. The laws of economics are just as unforgiving as the laws of physics. If too much money is created, the real value of a unit of money goes down ... The Federal Reserve’s preparedness to finance the coronavirus-related spending may prove suicidal to its long-term reputation as an inflation fighter ... If too much money is manufactured on banks’ balance sheets, a big rise in inflation should be expected."

He was correct about inflation but most people, including central bankers, ignored him. We revisited his opinions, most recently here, at the beginning of 2023. This is an edited extract from a video update in march 2023.

***

In developments in the global monetary scene. I want to focus today only on the three Western economies, the United States, the Eurozone and the UK. I'll say one or two things about China, India and Japan.

The message will be short and sweet, although perhaps not as sweet as it might be, because in fact, the news is rather worrying.

You will remember that back in early 2020 I pointed out the explosion in money growth that was then occurring in these economies, in the United States, the Eurozone and the UK, a bit elsewhere, but particularly really in those three economies. And we warned about a coming inflationary boom and rising inflation as economies return to normal after the COVID pandemic.

Money growth boom has collapsed

Today, the situation is radically different. We have had the inflation that was correctly forecast. Now, we have a collapse in money growth. And in the last few months, the quantity of money has actually been falling in all three of those places, the US, the Eurozone and the U.K. And even in the US, the change in money is not just a fall of a few months, it's fallen the whole year.

(This extract will not include the sections on the UK).

The coming recession in the US

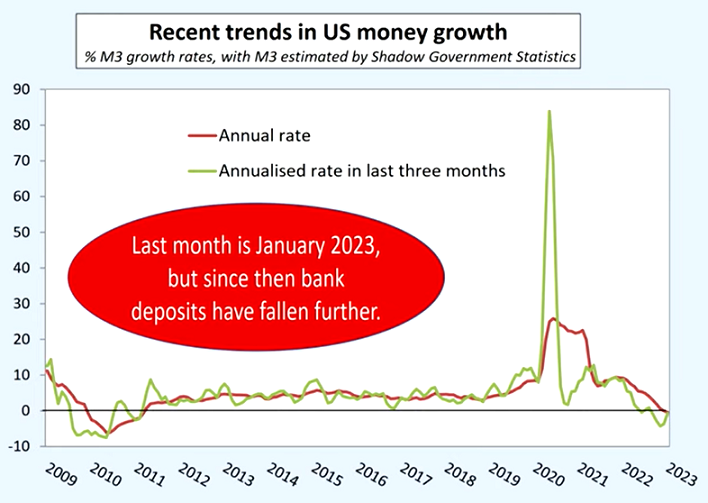

First, let's look at the United States since just after the GFC around 2009.

Back in 2009-2010, we had contractions in money in the US, followed by a period of stability. And then there was an explosion in 2020. On the 12-month measure, that's the brown line, the high money growth rolled through into 2021. It then comes down, and in the last few months, money has been actually contracting with the brown line finally going negative in the opening month of 2023. This chart finishes in January.

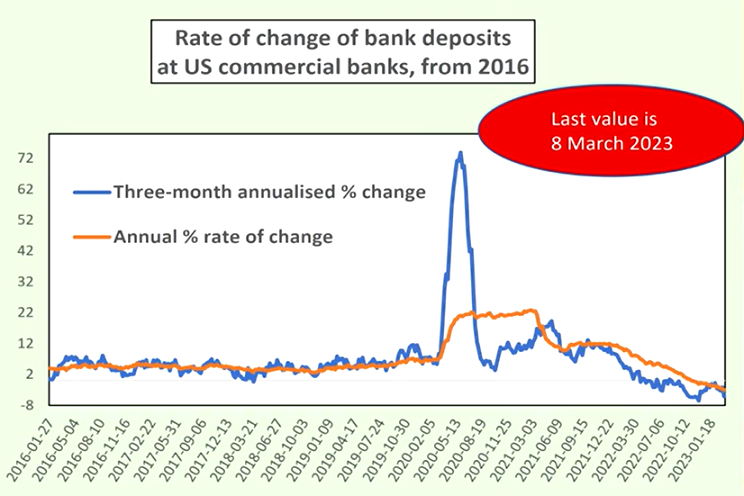

We do have numbers for bank deposits in February and two weeks in March. That's the quantity of money, which includes bank deposits and notes and coins. The detailed data on deposits is more frequent than M3.

What these figures show is that the quantity of money has continued falling, as deposits dominate money (M3). So, this is a continuing trend. Roughly speaking, money is going down at around about 0.25% to 0.5% a month. In the US Great Depression of the early 1930s, money was falling by about 1% a month. It's not that disastrous at the moment because there is still this cushion, an overhang from 2020 and 2021.

But the way things are going signals a recession and potentially quite a bad one.

These numbers are, of course, very different from what I was talking about three years ago, the boom/bust cycle, but it shows total incompetence on the part of the US Federal Reserve. But inflation coming down and probably, in 2024, coming down towards the 2% figure, which is the target that central banks have in mind these days.

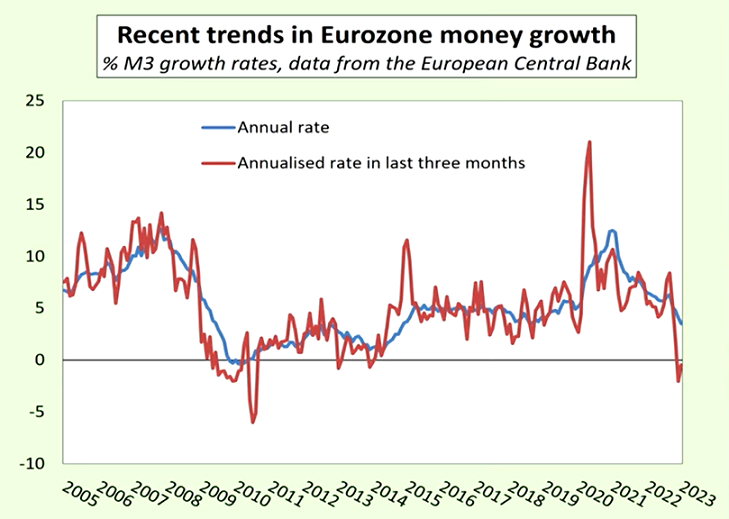

Eurozone also negative over next few months

The Eurozone for much of last year was very different. In fact, rather high money growth carried on until the final months of last year, then collapsed. Quite why this happened, I'm not sure, but that's what the data show. The 12-month change is still positive, with the blue line at about 3% or so, but well down from the figures over 10% in 2021. And the way things are going, this will probably go negative in the next three to six months.

This chart goes back to 2005 and the rapid growth of money in 2006-2007. There was a boom in the Eurozone then, particularly in the so-called Club Med countries – Spain, Portugal, Italy and so on. Then came a plunge, and a long period of rather weak money growth down at about 1% or 2% a year when in fact, the Eurozone, unlike the USA or the U.K. had a second recession.

Then 5% a year in the late 2010s, stable growth, low inflation, followed by a rapid growth of money in the COVID period, and now a collapse.

So you can see the connection between what's happening to money and what's happening to the economy, and this again is telling us that a recession is in prospect in the Eurozone. Some countries, in fact, have that negative quarters or even two quarters, but not as yet for the entire Eurozone.

A simple and obvious warning

This is a relatively simple, relatively obvious warning. What happened in 2007 to 2008 was that the banks got the blame. In autumn 2008, the powers at the G20 governments, their finance ministers, the central banks, the Bank of International Settlements and the International Monetary Fund decided that the banks must have more capital relative to their risk assets. There was a big rise for around about 60%-70% in the banks' capital requirements per unit of risk assets, per unit of loans to the private sector.

As far as whether you think that's desirable, the effect on economies was catastrophic because the banks started to pull in loans, to sell securities, to reduce their risk assets because they were required hold much more capital relative to those assets. And the result of that was to aggravate, to intensify the falls in the quantity of money, the falls in bank deposits.

To avert another Great Depression, the central banks then organised quantitative easing (QE) programmes where they bought assets from non-banks which increased the deposits held by non-banks and that did deal with the problem.

However, with the failure of SVB Bank, the absorption of Credit Suisse into UBS and so on, talk is of another round of increases in capital asset ratios for the banks, not just the banks that are delinquent. That will make any coming recession even worse.

That's my sombre message this time

I'm sorry it's a bit gloomy. One has to be direct about these things. I haven't dealt with the non-monetary theories of inflation that have been going around, but they are wrong. I have outlined here the move to contractions in the quantity of money and the risks that these will get worse if the regulators blunder as they did in 2008.

This is an edited transcript of the video: IIMR March 2023 Money Update: 'Quantity of money falling in the US, Eurozone and UK'. By T. Congdon.

Professor Tim Congdon, CBE, is Chairman of the Institute of International Monetary Research at the University of Buckingham, England. Professor Congdon is often regarded as the UK’s leading exponent of the quantity theory of money (or ‘monetarism’). He served as an adviser to the Conservative Government between 1992 and 1997 as a member of the Treasury Panel of Independent Forecasters. He has also authored many books and academic articles on monetarism.

This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.