Former Reserve Bank chief, Ian Macfarlane, wisely observed that in the US, easy money ends up inflating bubbles on Wall Street, but in Australia it ends up inflating house prices. This time last year, The Australian Financial Review was running stories like the following trumpeting double-digit growth in house prices across the country, driven by ultra-low interest rates and the generous Covid stimulus hand-outs.

The party is over

One year later, the stimulus party has finished, interest rates are rising, and house prices have started to give back some of those windfall gains. How far will interest rates rise, and how will they impact house prices?

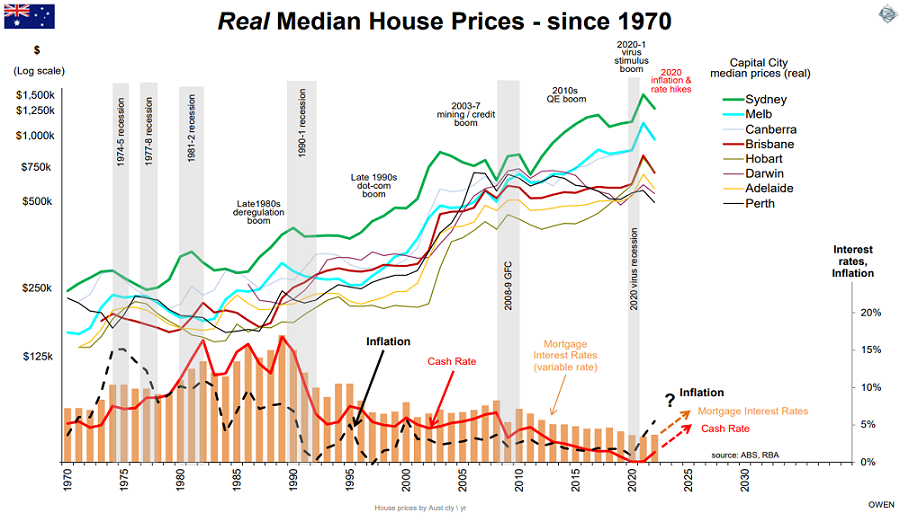

Here is an update on our regular chart of house prices, cash rates, mortgage rates and inflation over the past few cycles. Here we use real house prices (i.e., after CPI inflation), to highlight the inflation protection in housing.

There have been regular price booms once or twice per decade, including during periods of high inflation and interest rates, like the early 1970s, late 1970s and late 1980s. These booms were followed by periods of static or falling prices, usually during economic slowdowns when interest rates were being cut.

Yes, house prices do fall in real terms. Regularly.

We have just enjoyed a tremendous house price boom. In the three years to December 2021, median house prices surged by +43% in Sydney, Brisbane and Canberra, +41% in Melbourne, +62% in Hobart, +35% in Adelaide, but Perth was more subdued with +15% growth. Prices are falling now as there are fewer buyers with less loan money, and more sellers, including recent buyers with big mortgages.

Prices depend on interest rates this time

How far prices fall will depend mainly on how high interest rates rise, and for how long.

A neutral (non-inflationary) cash rate for Australia is around 3-4%, but if inflation does not quickly come back down to target range of 2-3%, then cash rates would probably need to be raised to well above ‘neutral’ first.

Central banks have a lousy record of controlling inflation without triggering economic slowdowns and recessions. There is no reason to think they will do any better this time.

It is unlikely house prices will give up all their 40% gains from the 2019-2021 boom. However, this might occur if aggressive rate hikes trigger a broad economic slowdown that brings high unemployment and widespread corporate and personal bankruptcies. We have had these before, in the mid-1970s, early 1980s, early 1990s, and the 2008-2009 GFC. The GFC was caused mainly by a global systemic banking crisis, but the Fed hiking rates from 1% to 5.25% was a major contributor to the housing collapse that triggered the banking crisis.

Despite these setbacks, housing is a long-term investment, and housing markets in Australia’s large cities have enjoyed a long upward march driven by:

- Population growth, mainly due to immigration

- Favourable demographics, with progressively smaller numbers of people per household

- ‘NIMBY’ supply constraints, and

- Tax advantages, such as exemptions from capital gains taxes and social security means tests.

These long-term fundamentals are likely to remain strong.

What lies ahead?

Although Russia is still waging war on Ukraine, and the Covid pandemic is still morphing into new strains, the main game affecting all types of investment markets is monetary policy. Can central banks contain inflation by unwinding their ultra-loose and ultra-expansionary monetary policies that created the inflation in the first place?

Political leaders, governments and central bankers have been quick to shift the blame for inflation to Russia, which is a convenient scape-goat. The problem is that, even before Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, inflation was already running at 7.5% in the US, 5.2% in the UK, 5.1% in the Eurozone (including 5.3% in Germany), and 3.5% in Australia. In 2021, central banks dismissed this inflation as ‘transitory’, and then in 2022 they jumped on the opportunity to shift the blame to Russia. The Russian invasion certainly added to supply restrictions (severely affecting poorer countries much more than the west), but the main problem was the trillions of dollars of stimulus money from governments and their central banks, sloshing around the market pushing up prices everywhere.

We are not in the blame game here. Inflation was caused by too much money chasing the supply of goods, services, labour, commodities, housing, shares and other assets. This excess money came from governments (loose fiscal policy) and their central banks (loose monetary policy). On the fiscal side, cutting spending and raising taxes to end the deficits, and even run surpluses to pay off debts, is going to be political suicide for elected governments, especially with fractured politics since the GFC in the US, Europe and even in Australia.

This will mean the heavy lifting will have to be done by central banks. Their primary tool is very blunt – increasing interest rates to reduce spending, by reducing peoples’ surplus spending money after paying the mortgage, and by taking away their jobs. There are early signs that some of the temporary supply constraints are easing, and that inflation numbers are starting to ease in the US, but is probably still rising in Japan, UK, Canada, most of Europe, and in Australia.

If central banks can manage to pull off a miracle and bring inflation back to target ranges without triggering economic slowdowns and big reductions in jobs, spending, and corporate profits, then the share prices of most companies are probably already over-sold at current levels. On the other hand, if the rate hikes do result in economic slowdowns that materially hurt profits and dividends, then share prices probably have further to fall. And so do residential property prices.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.