There is no doubt in the world of sport that the likes of 20-time tennis Grand Slam winner Roger Federer outperforms because of skill, not luck. When investors evaluate the performance of equity funds, however, it's not as obvious which funds are skilled or have just been lucky.

Fund manager league tables were recently released for the last financial year, and the media, as usual, trumpeted funds with hot performance.

But now is a particularly difficult time for investors to assess fund managers. With markets rising, some funds have just been lucky and ridden strong market gains. There is now a danger that investors chase these hot, lucky funds and become saddled with poorly-performing investments for years.

In this article we outline how investors can tell which funds managers have ‘skill’ and can be expected to outperform for a long time versus those that are simply lucky and likely to disappoint when markets change.

If investors can spot the difference, they are significantly more likely to choose the right fund that ultimately helps them reach their financial and lifestyle goals.

The skilled few

The big problem for investors is that few funds are truly skilled.

In a 2014 report on equity investing, Willis Towers Watson, the global investment consulting firm, argued that only 10% of fund managers could be considered genuinely skilled over the long term, while 70% show mediocre performance and 20% are inferior.

The fact that so few managers were deemed truly talented is a product of the multiple forces which influence portfolio performance, such as

- Luck

- Gambling on high-risk stocks during a rising market

- Having exposure to the right investment style at the right time

- Taking on hidden risks like selling put options

- Skill

Obviously, managers that perform via the first four should be avoided, but how can we tell who has the right qualities to be considered genuinely talented?

Four attributes of the skilled

Although no specific rule book exists on how this should be judged, we believe that skilled investors have four characteristics in common.

1.They perform through time

The number one attribute of skilled investment managers is their performance over time. By studying this, we can observe if performance has aligned with their intended investment style. For example, if they are a ‘growth’-style manager have they performed well when that style is in favour? If they are an ‘all -weather’ manager, have they performed well through all different kinds of market environments? We can also measure how persistent returns have been across different stages of the market cycle.

2.They have a high number of winning bets

Investors can also check the number of bets made over time. A manager who makes many bets over time, and wins a reasonable number of them, deserves to be rated far higher than a manager whose success is solely attributable to one or two knockouts. The former manager has been tested more times, and hence we can be more confident in their ability to replicate that success in the future.

3.They are on a quest for ‘better’

Besides only looking at each manager's track record of returns, those with skill at investing have an attitude to their craft that combines intensity, flexibility and humility. These managers have a passion for investing and are constantly striving to put in the work to become more skilled investors.

4.They accept the role of chance

At the same time, best-in-class investors are aware of the role of chance in their investment outcomes and don't try to paint their success as pre-ordained. By contrast, fund managers who don't realise how much chance impacts their results can end up being painfully stubborn or arrogant. And when the environmental variables that help outperformance eventually stop, a humble manager is more likely to adapt and evolve their process commensurately.

The harsh reality is that even a skilled investment manager will underperform at times, and an unskilled manager can outperform, potentially for years.

Still, the longer the period over which an investment manager delivers superior performance, and the larger the investment base involved, the more likely the results reflect skill rather than luck. To put this another way, over time as an investor becomes more skilful, their performance should become more consistent.

Like medical research

So how do professional fund manager selectors statistically test whether a fund manager’s performance is truly different from their benchmark, or the market?

They perform tests similar to the type used by medical researchers to test whether a drug’s treatment of a condition is statistically different from a placebo.

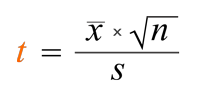

A simplified example of this test is below:

Where:

T = the so-called ‘test statistic’

X = a measure of the outperformance (if positive) or underperformance (if negative) of the fund versus the benchmark (the benchmark should be ‘risk-equivalent’ to the fund)

N = a measure of how long the fund has been operating

S = a measure of the volatility of the outperformance or underperformance of the manager through time

A ‘test statistic’ greater than about 2 means gives 95%+ confidence that the manager’s outperformance or underperformance is different to zero. This level of confidence is the most commonly used to determine if something is truly different from its comparator or baseline.

Three takeaway lessons

The size of the outperformance and the longer the manager’s track record are both positive attributes. Also, the lower the volatility of the outperformance, the more likely that outperformance is ‘statistically significant’ (different to zero) and due to skill rather than luck.

Some takeaways from this are:

- You should pay less attention to 12-month returns reported by the press in the newspaper because returns this short have a greater potential to be due to luck, rather than 3, 5 or 10-year returns.

- The larger the outperformance, the more likely this is to be due to skill, which can sometimes make up for a short track record. A word of warning though on this one: it is a good idea to test whether a manager has simply been ‘punting’ the fund and has made a big lottery-type payoff on one or a small number of bets, or whether it is due to a broader series of unrelated investments.

- Smaller, consistent outperformance may potentially be more likely to be due to skill than large, but volatile outperformance. There is a trade-off here.

Managers secretly skewing to small caps

More sophisticated statistical tests also exist to ensure managers aren’t simply outperforming by taking more risk than is embedded in the benchmark or market they are trying to outperform. A manager, for example, might claim outperformance during a bull market, but they only outperformed because they used leverage in their fund to increase its risk, and hence returns, in that market environment.

Finally, we need to question whether a fund’s investment returns represent exposure that could be obtained at a much lower cost by investing through passive-type products. In such instances, there is no need to pay fees to a skilful investment manager to access these returns.

For example, small cap equities, which is our space, have tended to outperform large caps across many different equity markets over long periods of time. Investors should turn their nose up at large cap managers who skew their funds to small caps, and where their small cap holdings have accounted for a meaningful share of their outperformance over their large cap benchmarks.

Sorting the skilled from the plain lucky

Don't put too much weight on a manager’s short-term annual returns reported in the so-called ‘leagues tables’.

At Ophir, we judge the performance of our funds, and our analysts who contribute to it, primarily on its size, duration, consistency and number of unrelated positions that have led to the result. We also seek to control for excessive risks that could jeopardise absolute performance over the long run.

We think there are two other key criteria that help the skill of any manager:

- Alignment: Nothing focuses your mind and skills like having your own money on the line when investing. As Charlie Munger has said: “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

- Capacity constraints: Size kills performance. Managing a lot of money is hard and it can impact nimbleness and force managers to operate in larger, more efficient markets where it is more difficult to outperform. As Warren Buffett has said: “Anyone who says that size does not hurt investment performance is selling”. A skilled manager who has been outperforming for years can quickly turn into an apparently unskilled manager whose performance drops off when they start managing a lot more money.

There are of other factors to consider when trying to disentangle the skilled from the unskilled but the above is what we consider the most important.

Andrew Mitchell is Director and Senior Portfolio Manager at Ophir Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

Read more articles and papers from Ophir here.