The threat of higher interest rates, slower economic growth, rising inflation and deteriorating credit is making investing scary at the moment, especially in equity markets. There are few risk-free places to hide, other than short-dated government securities. However, there are income opportunities not seen for many years. With all the focus on the cash rate, many investors do not realise how much long-term bond rates are already far ahead of short-term rates.

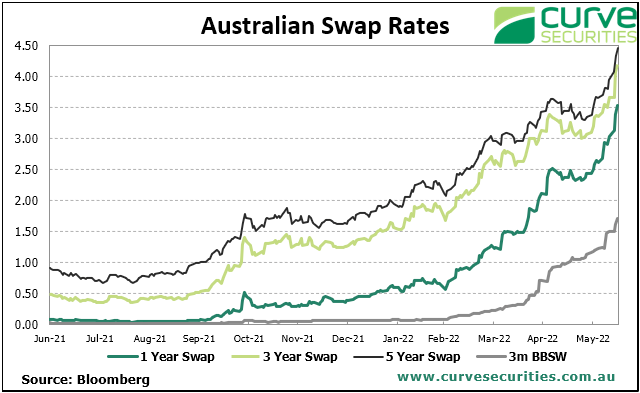

The increases in the bank swap rates in recent months have been dramatic, as shown in the chart below. With the five-year around 4.5% and high-grade securities offered at spreads of say 2% to 2.5% above the bank curve, fixed rate investors can achieve around 6.5% on quality names.

But even for investors willing to place money into bonds to take advantage of better yields, a decision is needed on whether to go fixed or floating.

Some intriguing investment opportunities

Let’s clarify some basic terminology.

A fixed rate bond means the coupon or interest rate paid over the life of the bond, say five years, is fixed for the term.

A floating rate bond means the coupon or interest rate varies according to a short-term benchmark, usually the bank bill rate in Australia, even if the term is the same five years. In other words, the rate changes every three months or 20 times over five years.

(Note that fixed interest rates have been moving significantly every day this week and the rates quoted in this article are illustrating specific points and may be out-of-date within a few days).

A recent transaction by Macquarie Bank shows the fixed versus floating opportunities. Macquarie issued a subordinated bond for $850 million and the market was happy with a credit spread of 2.7%. Investors had the opportunity of taking the 2.7% as a margin over the 3-month bank bill rate or as a margin over the five-year swap rate.

This transaction is known as a 10nc5, that is, the final term could be as long as 10 years with a ‘non-call’ period of five years. Issuers are expected to call after five years as they lose the favourable treatment as regulatory capital after year five. Macquarie was indifferent to fixed or floating because large borrowers can enter an interest rate swap to convert the fixed rate to floating or floating to fixed according to balance sheet need. Therefore, Macquarie allowed the market to decide the mix.

Based on demand, Macquarie issued $500 million of fixed rate and $350 million of floating rate. What are the investment opportunities?

1. The fixed rate component

Based on the five-year swap rate of 3.35% at the time of pricing and an issue margin of 2.7%, the fixed rate piece offered 6.05% (rates have risen since the deal was priced and it is now available above 6.5%).

For income-starved investors, here is a high-quality bank paying over 6% per annum for five years. Many retirees look to drawdown around 5% a year from superannuation as an income stream and this has been difficult to achieve for many years without depleting capital.

Two qualifications:

- the reason rates are rising is high inflation, and so real returns (after inflation) have not increased. However, if inflation falls from 2023 onwards, then 6% to 7% might look good.

- The debt is subordinated in the credit structure, a notch below Macquarie Bank deposits. It is rated Baa3/BBB/BBB+ (Moody’s, S&P, Fitch) which is the bottom rung of the ‘investment grade’ category, due to its subordination. The pricing was at a 0.1% to 0.2% premium for a new issue and about 0.2% more than CBA subordinated issues which are rated higher (Baa1/BBB+/A-) (Moody’s, S&P, Fitch).

2. The floating rate component

The floater also carries a 2.7% margin. Based on a bank bill rate of say 1.5%, the initial return would be 4.2% (2.7%+1.5%), or significantly less for the first period than on the fixed rate tranche.

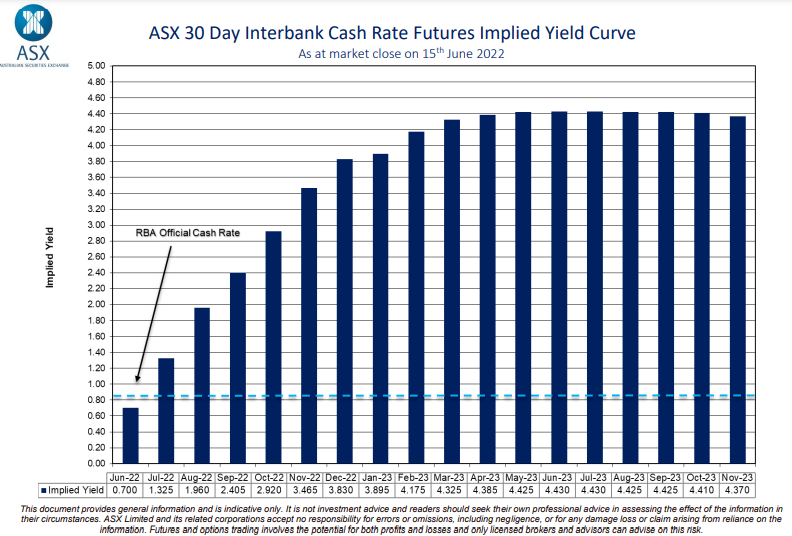

The chart below shows the 30-day cash rate futures curve until the end of 2023. At the time of writing, the market is expecting short-term rates to reach 4.4% by May 2023. A rate set with a margin of 2.7% would give a return of 7.1%, which is well ahead of the fixed rate tranche.

And therein lies the challenge.

Anyone who thinks the market is pricing rates too high should go fixed and grab the rate on offer now. Anyone who thinks the market is correct or rates will go higher should go floating.

(Note this bond is available to wholesale investors only but that is a surprisingly large group of investors, as explained here).

Remember that for fixed rate investors, two risks can send prices down: either term interest rates rise or credit spreads widen, so such an investment should be part of a diversified portfolio.

For investors who cannot access wholesale bonds, NAB recently issued a new hybrid (ASX:NABPI) paying 3.15% above the 3-month bank bill rate. Again, based on a bank bill rate of 1.5%, the initial yield will be 4.65% buying at par or $100 (prices will vary when trading on the ASX). This hybrid has an expected life of 7.5 years (hybrid spreads have widened since the date of writing this article. See the Firstlinks Education Centre for weekly price updates from nabtrade).

But if measured against the 4.5% bank swap curve and 3.15% margin, this hybrid may earn 7.65% in future. The return is similar to the franked yield on NAB’s shares without the equity market risk, based on the previous experience that hybrids are significantly less volatile than bank shares at times of market shocks.

Beneath the simple exterior of a floating rate bond, bank hybrids are complicated instruments, including conversion to equity in certain circumstances, but Australian banks are extremely well capitalised.

Retail investors can also consider bond funds, bond ETFs and listed bonds, either in fixed or floating structures, so these opportunities are not restricted to wholesale investors. For a floating exposure, check the fund's fact sheet for a repricing duration of 90 days or less. For fixed rate, the duration is more likely five or more years.

Your fixed versus floating decision

The failure of the Reserve Bank Governor, Philip Lowe, and its Board, to foresee the rampant inflation of 2022 shows that even with the best information in the world, forecasts are a guess. Lowe repeatedly stated until six months ago that cash rates would not increase until 2024, but now the market expects cash rates over 3.5% by the end of 2022.

Former Reserve Bank Governor Ian Macfarlane recently stated that the inflation target of 2% to 3% will be difficult to achieve and is more likely to stay around 5%.

Adding to the uncertainty, despite US inflation hitting a 40-year high of 8.6% last week, Bloomberg writes that “Inflation is poised to ease according to these three indicators”. The three items are falling prices of computer chips, shipping containers and fertilisers, all key input to the manufacturing processes of thousands of companies and products.

Either way, nominal yields available to investors now can make a meaningful contribution to the income required to keep up with inflation, and cash and term deposits paying 1-2% have serious yield competition. Fixed or floating, or a bit of each, bonds are back in the game.

A further update from Warren Bird

In 2016, fixed interest expert Warren Bird wrote an article called "Are we going through a bond market route?". Here is a follow up with his thoughts on whether fixed rates are value at current levels.

"Over the last two years, since July 2020, US 10-year yields have risen from 0.55% to 3.43%. That's 2.88% over 23 months. We're seeing negative returns over the two-year period for the typical Australian bond fund of 10-15%. It's not necessarily over yet, of course, so the record bear market move in the US of 3.25% in 1987 is well within reach and could easily be exceeded.

The lunacy of central banks ignoring how their QE had turned into money supply growth in 2020-21, resulting in them not acting to contain inflation a year ago when it was obvious that it was going to be an issue, means that even at 3.4%, the US 10 year Treasury bond is paying a big negative real yield at the moment.

But it's not as negative as cash, so I expect that the big end of town will start to nibble at buying bonds and lengthening duration from here. Cautiously, I suspect, but if the central banks do start acting to reign in their monetary policy accommodation and get us back to a more slow and steady with inflation, then from a longer-term perspective, yields are just about at 'fair value' levels."

Graham Hand is Editor-At-Large for Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Disclosure: Graham has invested in the fixed rate component of the Macquarie transaction and the floating hybrid of NAB, taking a bit each way in his diversified SMSF portfolio.