(Editor’s note: The following data and research relate to the US market, although anecdotally the same conclusions should apply in Australia).

Substantial research evidence supports the long-term predictability of returns based on factors such as dividend yields, Price/Earnings ratios, value and low volatility. However, investors are not reaping the benefits of such knowledge due to their timing of fund manager selection. By chasing winners from previous years, individual investors miss the mean-reverting factor and create underperformance, sometimes called a ‘return gap’.

Trend-following allocations push valuations

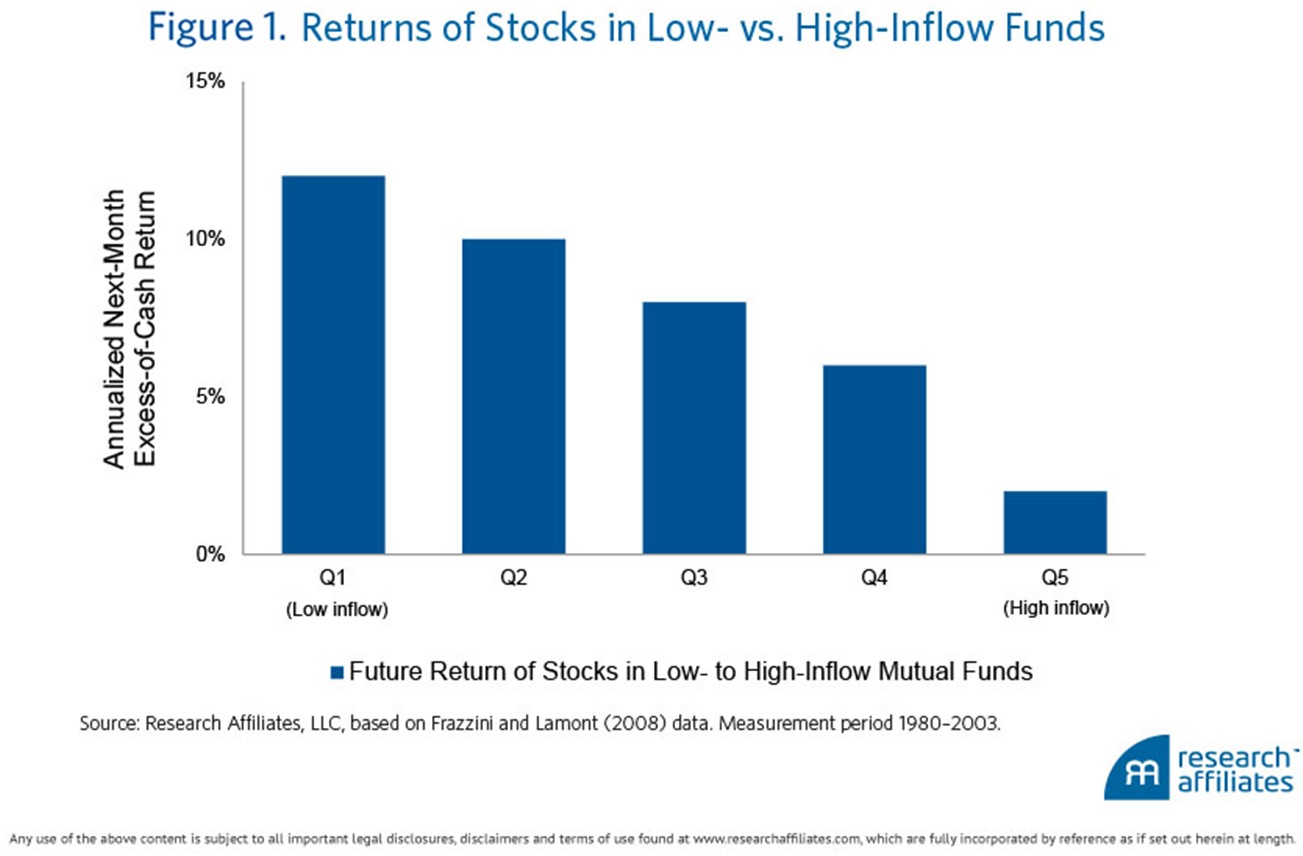

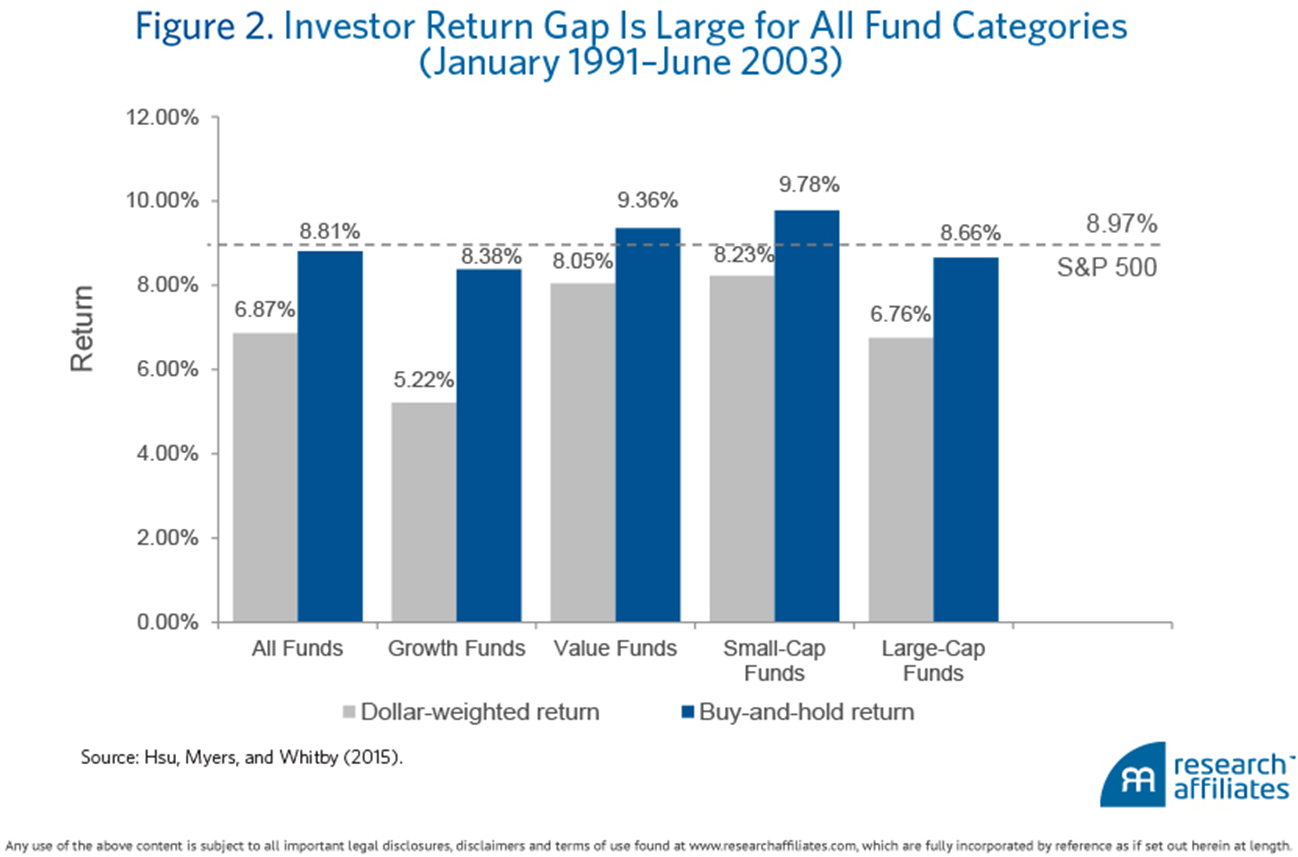

The procyclical or trend-chasing allocation accentuates the underlying economic shocks to various investment styles as flows push valuations. In the short run, this results in self-fulfilling prophecy and momentum. In the long run, it becomes self-defeating and gives rise to mean reversion. This investor pattern contributes to a predictive relationship between the valuation multiple and future return. As shown below, Frazzini and Lamont (2008) and Hsu, Myers, and Whitby (2015) find evidence that mutual fund flows predict negative future fund performance. Figure 1 shows that mutual funds with high inflows have low next-period relative performance. Figure 2 shows that the investor return gap, which is driven by the negative correlation between flows and subsequent returns, is large across all fund categories.

Alpha is a zero-sum game and so are flows

It is important to remember that flows are zero-sum, meaning that for every seller of a cheap value stock a buyer must exist on the other side of the trade. It is thus important to be clear about the investor cohorts being examined in the research. Most studies are based on mutual fund investor flows, with a few studies examining pensions and their allocations to institutional asset managers. The emerging evidence is that this particular investor cohort has earned negative dollar-weighted alphas on a gross-of-fee basis, as indicated by their large negative return gaps versus a buy-and-hold strategy. These negative return gaps are driven primarily by trend-chasing allocation decisions, which have largely been institutionalised by the investment industry through its hiring and firing decisions, the majority of which are based on recent performance. Given the poor performance of the adopters of modern investment selection practice, it is not unreasonable to label mutual fund investors and pensions as naïve flows, which are supplying dollar alphas to others.

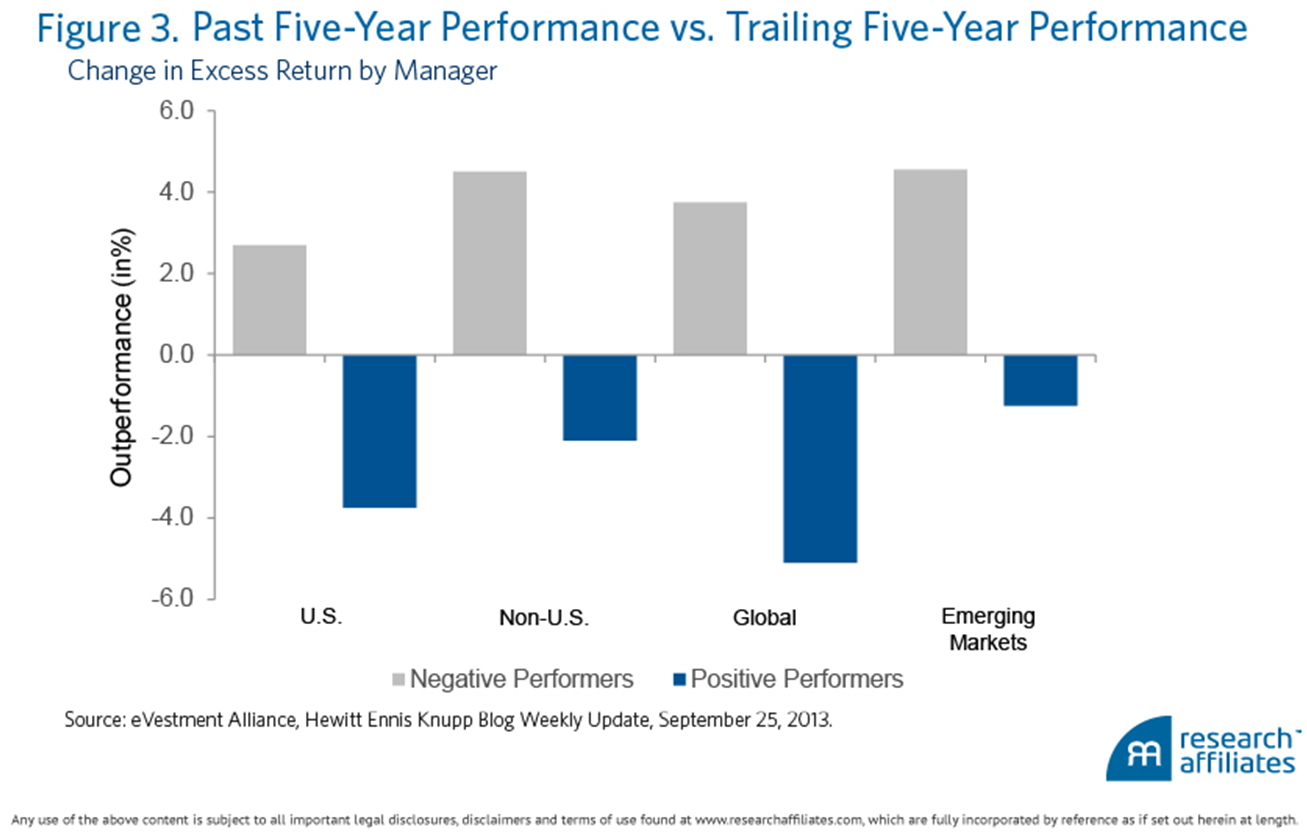

Ironically, the pursuit of positive alpha, which leads to the regular switching of investment strategies and managers, is the very reason why mutual fund investors and pensions have earned negative alpha. Investors should realise that the widely-followed selection practice is technically an attempt to time manager alpha. Figure 3, using institutional manager data from eVestment, shows that managers who underperformed in the previous five years tend to outperform in the next five years, while the outperformer tends to then underperform. As manager styles come in and out of favor, the hiring and firing of managers is akin to timing the returns of style factors. That procyclical timers, such as mutual fund investors and pensions, do poorly is the very reason why countercyclical factor returns persist.

The modern investment delegation practice is one in which manager skill has minimal impact on the wealth outcome of investors. To fully understand this, we need only examine the buying and selling activities of professional managers. In 1999, when value stocks were as cheap as they have ever been, value managers were the biggest sellers of value stocks. This was also true in 2008. It isn’t at all surprising when we realise that the selling is driven by redemptions! The manager could be doing exactly the right thing by tilting the investor’s portfolio toward value stocks. But by redeeming the allocation to value managers, the investor is able to more than offset the manager’s insight and effort. Individual investors delegate investment decision making to mutual fund managers. Pensions delegate investment decisions to institutional asset managers. Delegation is supposed to prevent less sophisticated investors from being the proverbial pig, slaughtered by better-informed bulls and bears. Putting aside the facts that the average investment manager charges just enough fees to extract all of the alpha they create, the delegation of investment decisions has failed miserably along a dimension that has received scant attention.

The wisdom or madness of crowds

The classic study on the wisdom of crowds suggests that a large collection of investors with different information, experience, and expertise tend to get prices right. Experiment after experiment shows that the crowd is better at figuring things out than the experts. Yet the wisdom of crowds can give way to the madness of crowds when the crowd herds on the same piece of information and/or adopts similar thinking. Experiments show that if the crowd is made aware of the presence of experts, its members synchronize to the expert opinion, and the wisdom that once was, is no more.

When the majority of investors adopt an investment selection process based on recent performance, they are forced to pile into similar stocks belonging to similar styles—that is, they allocate to an increasingly crowded trade. There is little wisdom in the prices that result, though the madness can certainly persist for a long while, creating the illusion of investment “guru”-ness on the part of many.

The institutionalisation of individual behavioural biases

The prognosis for improvement is unfortunately pessimistic. What started as behavioral biases—that we confuse short-term performance as vital information on manager skill, and that we enjoy blaming others and holding them accountable for random bad outcomes—have been institutionalised. No longer can behavioral biases be overcome by the greater mastery of one’s emotional state or by attaining greater investment enlightenment. These biases are now organisational problems that cannot be easily fixed by any single individual in the process. Would a consultant or financial advisor recommend a shortlist of managers with poor recent performance? Would the pension CIO and his staff choose a manager with a negative trailing three-year alpha to present to their layman board? Given a keen understanding of investors’ buying behavior, would salespeople and marketers educate client prospects on products that have recently underperformed? The investment ecosystem has conspired against the end investor. Oddly, the end investor is leading the conspiracy against himself. The path of least resistance is the path most often taken: buy recent performance.

The individual investor’s edge

Given the institutional challenges of traditional investment advice that plague pension sponsors and the wealth management industry, in general, a savvy individual investor could actually have an edge by being a contrarian in the modern investment-selection process. Buy the style that is out of favor and whose stocks are trading meaningfully below historical norm. Sell the popular style and its expensive stocks. The individual investor may be early in buying or selling, but has a far greater ability to deal with that potential discomfort than does an institutional investor. An individual is unencumbered by the constraints and oversights—a board, quarterly reviews, asset-raising goals, angry clients, or other pressures—that dominate institutional investment decision making.

Investors who have the courage to be a contrarian will earn a handsome 'fear' premium for taking the other side of the industry’s trades, counter to those who seek to avoid uncomfortable client conversations. For those unable to fully embrace a contrarian stance, they should at least consider adopting a buy-and-hold strategy. Indeed, most investors might benefit from simply forgetting the ID and password to their trading account.

Jason Hsu is Co-Founder and Vice Chairman of Research Affiliates LLC. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the personal circumstances of any investor. Readers should see their own professional advice. The full paper with greater detail, footnotes and references is linked here.