In the first three parts of this series over the last month, we have explored the ways governments can avoid repaying their debts in full; how Australia’s big default and debt restructure occurred in the 1930s; and the returns achieved by bond investors before, during and after the debt restructure.

In part 4, we look at the returns from the broad stock market versus the government bond market during the 1930s crisis. We see how the impact of the Greece-like default and restructure of government bonds affected bond returns, compared with the impact of the 1929 crash on share returns.

Bonds versus shares during the crisis

Despite the default and restructure for all domestic Australian bonds, bond investors who held on during the crisis (and refinanced their old defaulted bonds with new ‘haircut’ bonds), did better than share investors.

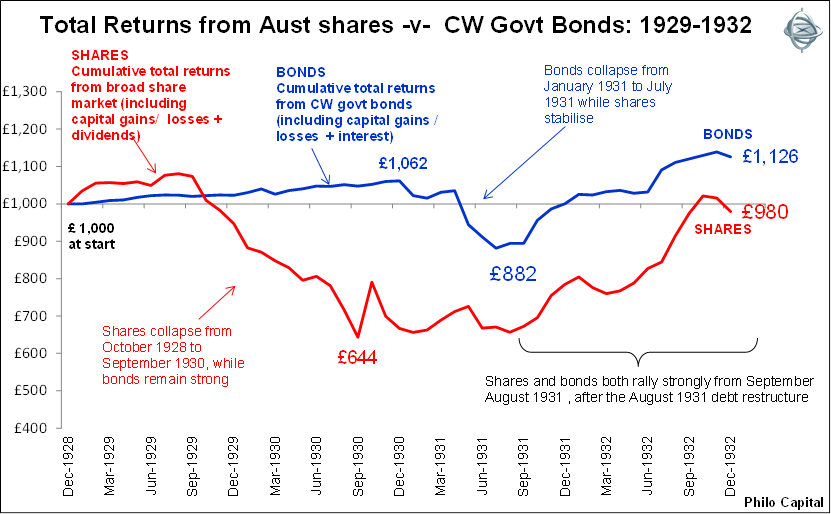

The chart below shows total returns (including capital gains/losses plus income) from the start of 1929 to the end of 1932. Share market returns are measured by the Sydney Commercial Index (the main index of large stocks across all of the main industries), including dividends paid. Bond returns are based on Commonwealth bonds maturing in five years or longer, including interest coupons.

For a snapshot of the key events during the period, refer to the chart in Part 2 of this series.

Income return was the same for shares and bonds but capital losses different

Share and bond investors received the same investment income over the four years: dividends from the broad share market gave investors 19% in total over the period, the same as the 19% interest paid on bonds.

The big difference was in the market prices of shares versus bonds. Share prices fell twice as far as bond prices, dropping 46% from the peak in 1929 to the bottom in August 1931. Share prices started to recover in September after the August 1931 debt restructure deal. The broad share index was still 20% lower by the end of 1932, whereas bond prices had recovered to par. However the 20% capital losses on shares were almost made up for by dividend income, leaving investors almost square after four years, and ahead 15% in real purchasing power terms after the general price deflation of 17% over the period.

These are very good investment returns for the four years during the worst of the ‘Great Depression’: 29% real total returns from government bonds, including the default and restructure, and 15% real total returns from shares, including the 1929 stock market crash!

Three phases of the crisis

There were essentially three phases of the crisis, and shares and bonds did different things in these three phases. The first phase was late 1929 to September 1930. During this phase share prices collapsed while bond prices remained strong. Investors dumped shares in the panic and bought government bonds as a ‘safe haven’. Some safe haven, as the government defaulted.

Share prices nearly halved over the period, which included the October 1929 ‘crash’, which was much milder in Australia than in the US because Australia did not have a wild speculative bubble in the late 1920s, and so there was no bubble to burst. Australia was already in recession, in 1928-1929, commodities prices had already collapsed, and credit markets had already dried up for Australia (thanks primarily to the profligate NSW government).

The second phase was between September 1930 and the August 1931 debt restructure. Share prices stabilised after the August 1930 ‘Mobilisation Agreement’ under which the commercial banks agreed to lend the Commonwealth government £3 million per month to pay interest on debt and to keep the government running. Shares stopped falling but bonds (the so-called ‘safe haven’) collapsed, all the way to the August 1931 default and restructure.

The third phase was after the August 1931 debt restructure, when prices of shares and bonds recovered strongly together.

Not only did Australian shares suffer less than US shares, they started to recover a year earlier than US shares. The main reasons were that Australia abandoned the gold standard and depreciated its currency more than a year earlier (from January 1930), and also because Australia did not go on a Keynsian debt-funded spending spree – because it was simply unable to borrow from domestic or international debt markets.

Investors’ worst fears were realised

As usual, the best returns were received from buying in the depths of despair, when there is ‘blood in the streets’. Investors’ worst fears were realised: the government failed to pay interest and principle on its entire stock of domestic bonds and notes. Interest payments were slashed 22.5% across the board and bond holders had to wait up to 30 years to get their money back. The ‘worst case scenario’ turned into fact, but returns were still very good for bond investors, even through the default and restructure.

The same was the case for the defaulted Greek bonds in 2012. The ‘worst case scenario’ came true – the government failed to pay and the debt was restructured in a ‘haircut’ deal, but there was still plenty of money to be made. Several hedge funds made a mountain of money buying off panicking investors at the depths of the crisis. The losers were the investors (mostly European banks and pension funds) that sold into the fear.

Australian investors, bonds and listed bonds

By the way, recently there has been much chatter in the ill-informed national media about Australians not being accustomed to bond investing, and also not being accustomed to bonds being listed on the stock exchange. This is complete nonsense.

The recent listing of bonds on the ASX is nothing new. Bonds were listed on Australian stock exchanges for more than a century. Bond-holding has exceeded share-holding for Australian investors for most of our history. In addition, bond trading has exceeded share trading on the main public exchanges in volume and depth for most of the history of stock exchanges in Australia.

Shares only overtook bonds as the preferred investment for Australians in the late 1960s, thanks to two main factors. The first was the speculative mining boom of the late 1960s, in which almost all of mining stocks that appeared in the boom promptly disappeared worthless in the crash that followed. The second factor was tax: specifically the removal of tax rebates on bond interest in 1969, followed by the granting of franking credits to shareholders in 1987. Australia is like almost all other ‘developed’ countries in the world, where bond investing has been more popular and more widespread than share investing for most of its history.

This concludes our 4-part story of Australia’s big government debt default.

Ashley Owen is Joint CEO of Philo Capital Advisers and a director and adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund.