There is a common belief that family trusts have limited uses unless there are beneficiaries on lower rates of tax to distribute income to. In fact, some argue their purpose is lost.

This view is simplistic because there are other benefits of trusts beyond distributing to individuals on lower incomes. This article focusses on the use of 'bucket companies' in family trusts.

The use of bucket companies

A bucket company is a corporation and a beneficiary of a trust whose job it is to hold on to distributions. In other words, it is a corporate beneficiary. The advantages of distributing trust income to corporate beneficiaries lie in the facts that:

(a) companies, as opposed to individuals, pay a flat rate of tax on income which is often less than the applicable individual tax rate, and

(b) whilst a trustee is compelled to distribute the income of the trust, thereby incurring a tax liability for those individuals who receive a distribution (at whatever rate), a corporate beneficiary can hold those distributions. If there are franking credits available, there might also not be a ‘tax differential’ to pay on those distributions.

There are tax rulings which require care when structuring these arrangements so as not to fall foul of the provisions of Division 7A of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936, which deems certain payments to shareholders or their associates as dividends.

Please also note that this article considers trust income, rather than distributions of capital gains through trusts, which are taxed differently. Furthermore, the examples used here only apply to private companies and not listed companies.

Prerequisites for a bucket company structure

Three preconditions must exist for a bucket company to function:

- There needs to be a trust with income to distribute.

- The trust deed of the trust must allow for corporations to be beneficiaries.

- The corporate beneficiary must fall within the definition ‘beneficiary’ under the trust deed.

Taxing of trust income

The general principle is that the net income of a trust is taxed at the hands of the beneficiaries. Individuals and company beneficiaries pay tax on their portion of the trust’s income at the rates that apply to them.

Currently, the highest marginal tax rate for individuals (not including the Medicare levy) is 45% for people with a taxable income of $180,000 or more. For passive income companies, there is a flat tax rate of 30% (or 27.5% if the small business tax rates apply).

So, other things being equal, the current difference between these two tax rates is at least 15%. On the same income distribution, say $100,000, a corporate beneficiary would pay at least $15,000 less tax. While corporations do not have a minimum tax threshold due to the flat rate of tax, most individuals have a marginal tax rate over 30%. The 32.5% marginal tax rate currently kicks in at $37,001.

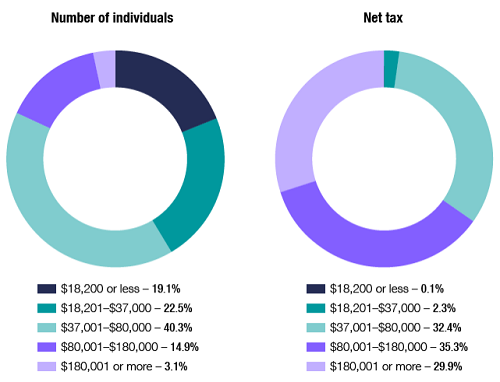

Number of individuals and net tax by tax bracket, 2016/2017 income year

Source: ATO Taxation Statistics

Corporations as beneficiaries

The beneficiaries of a trust can be specifically named or they otherwise fall within the broader definition of being within a “class of beneficiary” under the trust deed. For instance, where a corporation is not specified as a beneficiary, a typical trust deed should have a definition creating beneficiary classes which includes corporations that are wholly or partly owned by individual beneficiaries.

For example, Joanna is a beneficiary named in a trust deed. Most trust deeds should include a clause which allows for distributions to a corporation that Joanna controls, even though that corporation is not specifically named in the trust deed.

What to do with the distributions in the company

Once it is established that the corporation may be classified as eligible for a distribution, it will receive the distribution and be liable to the ATO for the tax payable at the corporate tax rate.

As the distribution and (usually) cash now sits in the corporation, there arises a practical question about what to do with it. This depends on the strategy in place. For some, the purpose of a bucket company (having paid tax on it at a lower rate) is to hold the distribution until some point in the future when it can be distributed to individuals.

Another strategy involves loaning the cash. If the loan is to a related entity, a Division 7A-compliant loan arrangement is needed. Always be cautious when loaning funds from corporations to related entities because they can run foul of tax rules.

Consider this example: John has set up a trust to be the shareholder of his company. He also has a corporation he can nominate as a bucket company to be a beneficiary of this trust. John is on the highest marginal tax rate and has no one else who he can distribute to. The company declares fully franked dividends, and John uses the bucket company to take the distribution, and after that then loans that money to himself so he can purchase an asset. John would have to enter into a Division 7A loan arrangement with the company and repay the loan in accordance with those terms. The benefit here is that John can realise the benefit of the dividends (via the corporate beneficiary) without incurring the obligation to pay the highest marginal tax rate on those funds upfront. The tax obligation is spread over a longer term.

It may also be possible for the corporate beneficiary to deduct expenses from the income it receives from the trust. A possible scenario might be to distribute to a corporation that has carried-over tax losses from previous financial years, but watch for carried-forward tests. The value in this could be considerable because, in the case of dormant companies with carried-over losses, it may not need to go back into trading to realise the benefit of those losses from a tax perspective.

Sometimes it makes commercial sense to move only the retained earnings out of a company. This is a ‘balance sheet exercise’ which involves moving profit out of a company without transferring cash right away. Examples include where the company has been using its profits to aggressively pay off debt. In these situations, the company will accumulate valuable franking credits and retained earnings and it can make sense in some circumstances to move these out of a company rather than leaving them there exposed to commercial and legal risk. The franking credits can be used up thereby creating a channel for the distribution of income in the future.

Approach with caution and professional advice

It is not possible to cover all aspects of this subject in a short article.

This article has summarised the potential benefits of using bucket companies such as:

- To take advantage of lower rates of tax paid by corporations.

- To hold retained earnings and franking credits until needed.

- To offset expenses and carried over losses incurred by corporate beneficiaries against distributions.

- To use loans to related (and unrelated) entities to purchase assets without paying upfront tax at the highest tax rates.

A note of caution and technical qualification.

Although the use of bucket companies in family trusts in particular is common, simply taking advantage of the lower rates of tax applicable to corporate beneficiaries is not without consequence or risk. For instance, the ATO considers that Division 7A may apply to an unpaid present entitlement of a corporate beneficiary where the trust and the beneficiary are related entities. This position is found in TR 2010/3: Income tax: Division 7A loans: trust entitlements, which is not without its critics. Practice Statement PS LA 2010/4 sets out the procedure and requirements for the establishment of a sub-trust to take advantage of exemptions from Division 7A.

Jacob Carswell-Doherty is Solicitor Director at Foulsham & Geddes law firm. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual. Personal advice should be taken before acting on any information.