Local retailers have seen their shares sold off recently in a gathering fear that when Amazon comes to town it will destroy their markets and profit margins. In June, Amazon expanded into the grocery business and its shares hit $1,000 for the first time. It listed in 1997 at $23.50.

Amazon has been a fascinating company to watch but I have never bought shares in it directly. Amazon created a new global market 20 years ago - online retailing - and it has dominated the market ever since, but it has never been able to figure out how to make a profit from it. It has never paid a dividend and never plans to in the future. At first glance it sounds like a crazy business plan and a lousy investment. Surely a company that never intends to pay a dividend is a crazy gamble that can only pay off if you can find a ‘bigger fool’ to sell it to for a higher price in future.

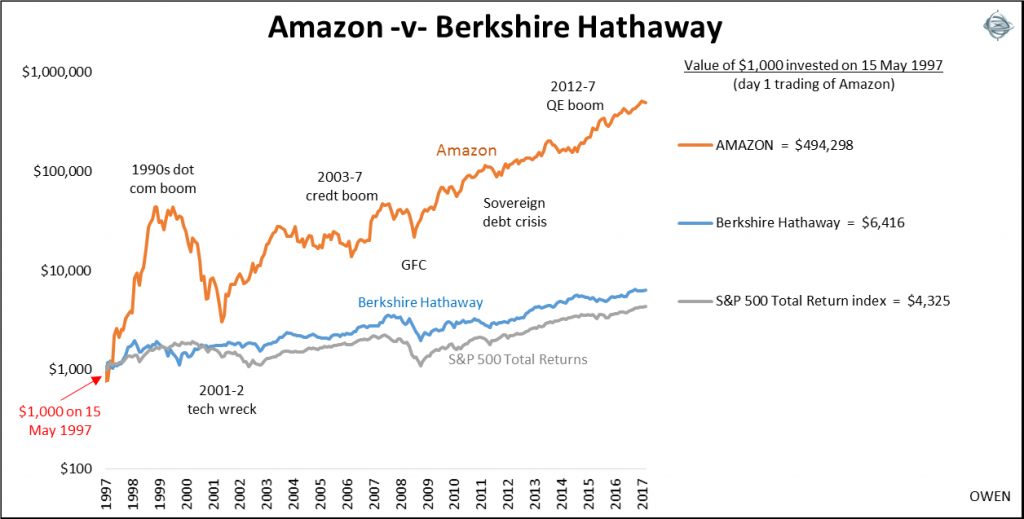

Meanwhile Amazon shares have rocketed upward. If you invested $1,000 in Amazon shares at $23.50 on the first day of trading on 15 May 1997, your initial $1,000 would be worth $494,000 today. That’s a return of 36% per year over 20 years (Amazon shares have split 12:1 over the period). But still no dividends!

Our obsession with dividends is misplaced

Australians have always been obsessed with dividends but I would much rather invest in a company that retains its capital instead of paying it out in dividends - if it can earn a higher rate of return on its capital than I can earn if it gave the money back to me. Over the years, my best returns from shares have been in companies that never pay dividends.

For example, I have been a shareholder in Berkshire Hathaway for many years, a company controlled by the world’s greatest living investor since 1964. Under Warren Buffett the company has never paid a dividend and never plans to. Buffett and his offsider Charlie Munger can earn a higher return on the capital than I can, so they keep the capital in the company and re-invest it to grow faster than I can grow it. Returns on Berkshire Hathaway shares have beaten the broad US stock market by more than 2% per year since Amazon was listed. That’s a great result, but well behind Amazon (Berkshire shares hit $1,000 per share back in 1983 and are now $254,000 per share, and that’s US dollars!).

Amazon shareholders let its founder Jeff Bezos keep the money in Amazon and re-invest it to expand the business, just as Berkshire shareholders let Buffett and Munger keep the money to re-invest it and expand. Rather than declare profits and pay tax, Amazon chooses to spend the surplus cash to expand. That’s how it grew to be the largest retailer on the planet. It has never had to raise equity since the initial $300 million raised in the 1997 float. Likewise, the vast bulk of Berkshire’s ‘profits’ are unrealised gains on their investments. They rarely sell anything and they have financed it all internally by not paying dividends.

Amazon and Berkshire are very similar. Both have grown to be in the top 10 most valuable companies in the world by reinvesting their cash flows. Both are impossible to value as they have no real earnings and no dividends. But Amazon is running out of space. It can’t keep growing forever at the same rate (unless it invades and populates another planet or two) and Berkshire is running out of time. Buffett and Munger are 86 and 93 years old respectively.

Many investors hold both Amazon and Berkshire Hathaway indirectly in diversified portfolios because they are both in the largest dozen listed companies in the world (each is about 1% of the global stock market value) and therefore feature in global share index funds.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at privately-owned advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.