In 2011, the Reserve Bank of Australia set out to create a policy-induced housing construction boom to fill the hole being left by the collapse of the 2003-2011 mining construction boom. It cut interest rates 12 times between November 2011 and August 2016 to levels never before seen in Australia, to lift house prices and lower borrowing costs to encourage development.

House prices are important for Australian investors for several reasons. The local economy and stock market are heavily reliant on the local banks remaining solvent and lending. Our big banks make up one third of the local stock market value and they pay one half of all dividends.

The vulnerability of banks

The problem with the banks has four main elements:

- they are extremely highly leveraged (at around 20:1, for every $1 of debt there is 5 cents of equity capital)

- they are highly exposed to the local housing and housing construction industries

- they are heavily reliant for funding on fickle foreign markets, as Australia’s conduits for foreign debt, and

- mortgage interest rates are extraordinarily low and rising rates will put pressure on highly geared borrowers.

The pattern of mining booms switching to housing construction and lending booms that collapse in bank bad debt crashes and economic recessions is not new. The 1870s-80s mining boom (which gave birth to BHP, Rio and many others) turned into the 1880s housing construction and lending boom which collapsed in the bank bad debt crash in the early 1890s, triggering a deep economic depression. The 1960s mining boom turned into the early 1970s housing construction and lending boom which collapsed in the property finance crash in 1973-1974, triggering the deep 1974-1976 recession. The early 1980s ‘mini-resources boom’ expanded into the mid-1980s ‘entrepreneurial boom’ which after the 1987 crash turned into the late 1980s construction and lending boom which collapsed in the bank bad debt crisis in the ’recession we had to have’ in 1990-1991.

Problems looming in apartments but not houses

In each of these cycles, Melbourne saw the worst of the excesses in construction and lending and suffered worst in the crashes, in terms of price falls, vacancies, bad debts, business failures and unemployment. In the current cycle Melbourne is once again leading the charge (along with Brisbane), while the excesses are less severe in Sydney and other cities.

The main problem is not in the broader suburban housing market but in high-rise construction. As in all previous cycles, the current over-construction will result in high vacancy rates, boarded up building sites, properties lying empty for years, falling rents, falling prices, bankrupt developers and bankrupt over-extended buyers. As in past cycles the problem for the banks will mainly be property developers, not just the highly-leveraged buyers.

This has happened several times before and it will happen again. The risk for investors is that the collapse in the high-rise market will probably also infect the broader economy and the broader housing market as well.

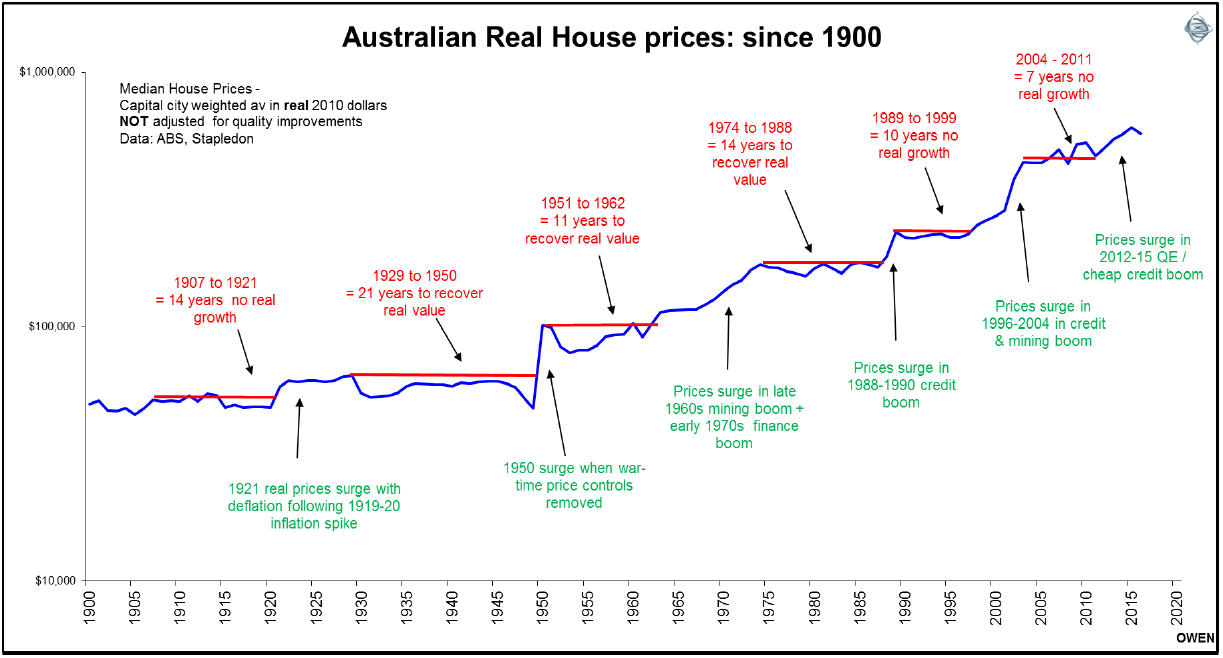

Our broad housing market has not suffered big crashes as it has in most other countries. Our high rates of immigration and population growth and extreme concentration of population in a few large diversified cities ensure broad house prices have tended to rise rapidly for a few years every decade or so, and then go sideways in real terms for several years.

There are regular price falls of 10% to 15% or so but no major broad-based collapses like in the US and many other countries. We easily forget that as recently as the seven years from 2004 to 2011, there was no real growth in house prices following a surge from 1996 to 2004. We have had five periods since 1900 when real house prices have not risen for a decade or more.

While the Melbourne and Brisbane high-rise markets are probably heading for another sizable collapse similar to past boom-bust cycles, the most likely outlook for the broad housing market is for modest price falls in housing and then many years of no real growth, rather than a sudden major crash.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at independent advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.