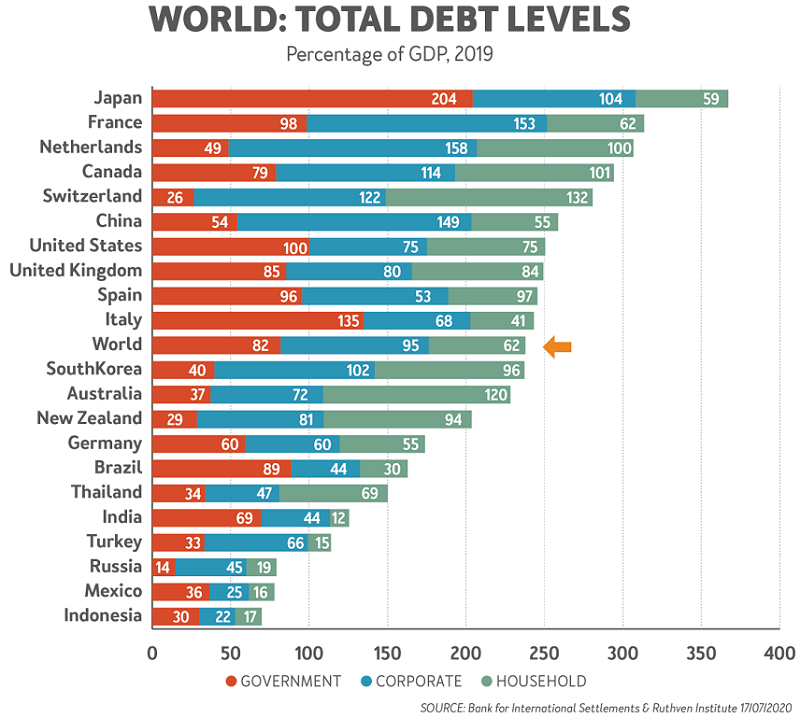

The world is swimming in debt, as high as it had been before the GFC in 2008, with government debt-bingeing establishing all-time records due to the mishandling of COVID-19 health-wise.

The world is heading for a debt level of 300% of GDP or more, Japan is nudging 400%, and four other countries are heading over 300% in 2020. Among the big 10 economies, our nearest neighbour - Indonesia - is the least indebted with less than 100% of GDP.

Australia joins the debt party

Until March 2020, Australia was relatively well-behaved, with a total debt of less than 250% of GDP. Our government debt, at 37% of GDP in 2019, was only bested in the developed world by Switzerland at 26%. The main risk was our household debt (mostly mortgage debt) at 120% of GDP.

All that changed with the announcement in the first half of 2020 that we would be spending $360 billion to fight COVID-19, despite there being less deaths from the pandemic than normal respiratory deaths (mainly the over-70s age group) in previous years.

On the Budget night, the cheque book came out again. Now we have prospects of a government debt of $1.7 trillion by end 2024, or over 80% of GDP. That would put Australia’s total debt closer to the 275% of GDP mark.

Is this serious? Yes, but not debilitating.

The economy will almost surely suffer more from the shutdowns, and general deprivation of commerce and liberty, including the controversial border closure of 2020. Around 1-in-7 businesses shut down in good years, or some 280,000 businesses of the total 2.3 million. That share may rise to 1-in-5 or 6 for a year or two.

Debt versus servicing costs

Debt is always less of an issue than its servicing cost be it as a share of government revenues, business revenues or household disposable incomes.

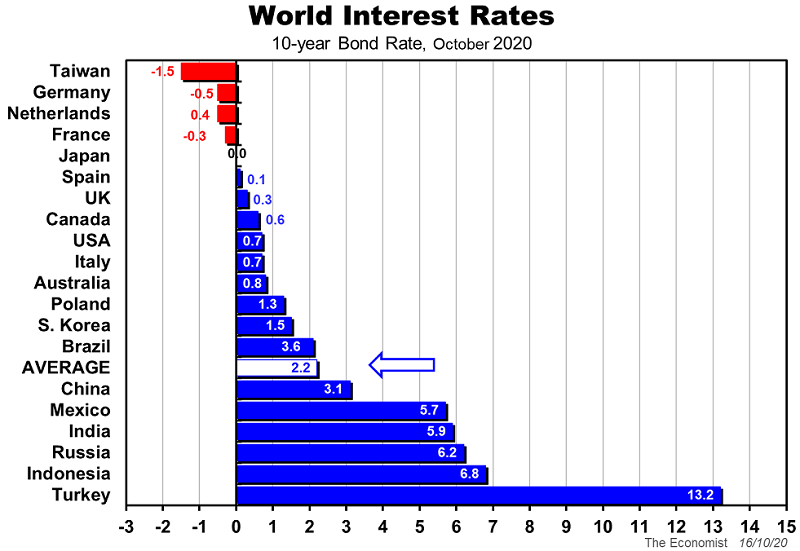

So, interest rates are just as important as the debt levels. The chart below provides perspective on government debt servicing costs via the 10-year government bond rates across various countries.

Australia’s bond rate means that, even if it climbed back to 2% by 2024, it would only account for 5% or less of all government revenue (taxes and other income).

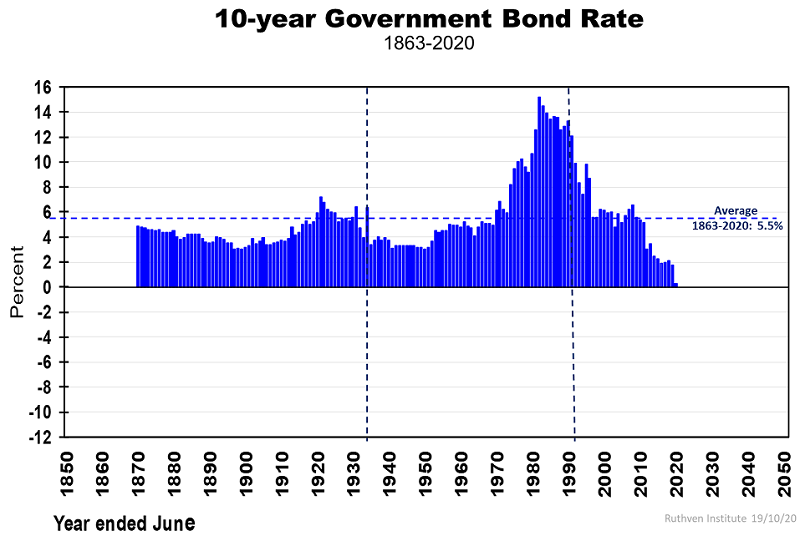

The next chart shows the long history of 10-year bond interest rates, which have averaged 5.5% over the past 150 years, but are now less than 1% and seemingly at a record low.

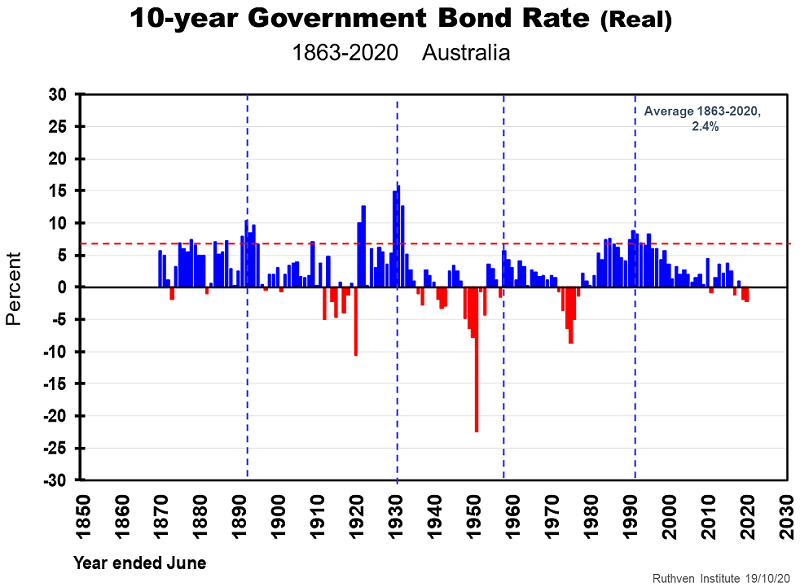

But when converted to real interest rates, by deducting inflation, we are far from a record low. Indeed, there have been at least 15 years when the real interest rates were lower than in 2020.

What all this means is that the debt and its servicing is probably less of a problem than repairing and re-building the wrecked economy, especially in Victoria.

We can service the debt. But of course, if and when bond rates go back to 5% (a long way off it would seem), governments will pray for higher inflation for several years to dilute the debt mountain. That’s what happened in the 1950s, when inflation (including one year at 25.25% in 1953) diluted the WWII national debt of 110% of GDP to a very manageable share of GDP.

More serious than debt

The more serious problems for the next 5-10 years are:

- How to get the economy back on its feet and restore our standard of living (GDP/capita) back to the March 2020 level before 2025.

- What to do differently with the next pandemic, bound to arrive well before the end of this decade.

- How to restore our international trade in the huge and fast-growing Asia region with the problems and tensions there, from COVID-19 (closed borders), trade wars and hegemony.

We need better long-term vision, innovation, reforms (I have covered the subjects of parliamentary, labour market, taxation and commerce reform previously), statesmanship and management than we have had over the past 10-15 years or more. And that goes for corporate Australia too: we are lagging well behind world best practice (WBP) innovation, performance and profitability.

That said, who of us would prefer to live elsewhere in this extraordinary and turbulent world of the third decade of this 21st century?

Phil Ruthven AO is Founder of the Ruthven Institute, Founder of IBISWorld and widely recognised as Australia’s leading futurist.