In 1877, the US rail and shipping tycoon, Cornelius Vanderbilt, died. He was the wealthiest man in the world with a fortune then worth more than US$100 million. His eldest son, Billy, inherited 95% of Cornelius’ assets.

Six years later, Billy had almost doubled his inheritance via several canny business deals. Yet, a quarter of a century after that, there wasn’t a single heir or member of the Vanderbilt family who was among America’s richest. Vanderbilt had given the original gift to the university that bears his name in Nashville, Tennessee, and when 120 members of the family met at the university in 1973, not one of them was a millionaire.

How such gargantuan wealth evaporated is difficult to fathom. What happened?

In their recently published book, The Missing Billionaires, Victor Haghani and James White, suggest that if “the Vanderbilt heirs had invested their wealth in a boring but diversified portfolio of US companies, spent 2 per cent of their wealth each year, and paid their taxes, each one living today would still have a fortune of more than US$5 billion.”

The Vanderbilt’s case of disappearing wealth isn’t unusual, albeit the scale of it is. In 2022, “there were just over 700 billionaires in the United States, and you’ll struggle to find a single one who traces his or her wealth back to a millionaire ancestor from 1900.” In fact, “fewer than 10% of today’s US billionaires are descended from members of the first Forbes 400 Rich list published in 1982. Even the least wealthy family of that 1982 list, with ‘just’ $100 million, should have spawned four billionaire families today.”

Why there aren’t more billionaires descended from the scions of old-money wealth is the basis for the book.

When genius failed

It’s worth mentioning the backdrop to the book. Most of you would have heard of the legendary fall of hedge fund, Long-term Capital Management (LTCM), in the late 1990s. Briefly, LTCM was set up by John Meriweather, a well-known former trader at Salomon Brothers. The board boasted some of the world’s finest financial brains, including Nobel Prize winners, Myron Scholes and Robert Merton.

Initially, LTCM achieved impressive results, with net annualized returns of 21%, 43%, and 41% in the first three years, respectively. But in 1998, it made an astonishing loss of US$4.6 billion, due to a combination of extreme leverage and poorly executed options and arbitrage bets. Fearing financial contagion from LTCM’s losses, the US Federal Reserve helped organize a US3.6 billion bailout package.

In the aftermath, the LTCM implosion became a tale of how smart people with sophisticated mathematical models could still do very stupid things.

It turns out that one of the book’s authors, Victor Haghani, was a bond trader at LTCM who lost a nine-figure amount in the fund’s collapse.

In this light, his book on strategies to manage wealth wisely seems appropriate, if not a little ironic.

The disappearance of Australian family wealth

Before I get to the book’s answers, it should be noted the story of missing billionaires isn’t just an American phenomenon. There are plenty of Australian families that have blown large inheritances too.

Though the history of Australia’s wealthiest individuals is patchy at best, I tracked down a list of the richest men (as they were then) from 100 years ago:

- Macpherson Robertson

- E.N. Abrahams

- George Juda Cohen

- Sir Samuel Hordern

- Hugh Victor Mckay

- Sir Rupert Clarke

- Anthony Hordern

- John Wren

- Lebbeus Hordern

- J.H. Riley

- W.G. Angliss

- W.L. Baillieu

- H.W. Grimwade

- Alfred D. Hart

- Sir Hugh Denison

- F.B.S. Falkiner

- John Darling

- John Brown

- Geoffrey Fairfax

- J.O. Fairfax

As far as I’m aware, no family members from this list are in the top 50 richest Australians in 2024, meaning much of the wealth has been squandered in the years since.

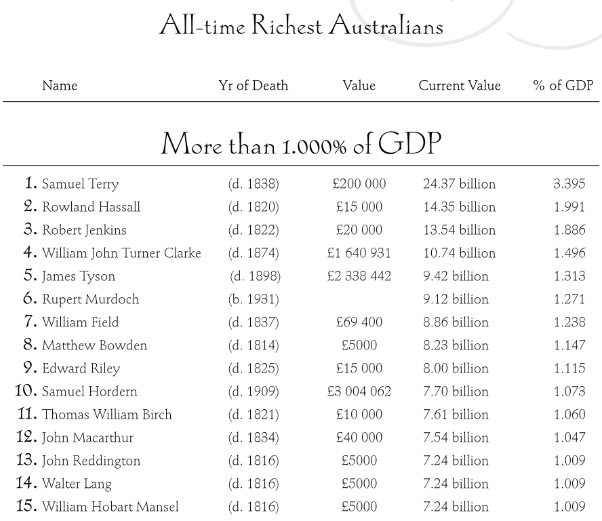

In his 2004 book, The All-time Australian 200 Rich List, William Rubenstein tried to calculate the wealthiest-ever Australians. To do this, he took the wealth of individuals at their deaths as a percentage of the GDP at the time.

According to Rubenstein, the richest-ever Aussie was Samuel Terry, the ex-convict known as the ‘Botany Bay Rothschild’. Terry died with assets valued at £200,000, equivalent to 3.395% of GDP in 1838, or around $86 billion today. That compares to Australia’s richest person now, Gina Rinehart, with wealth worth $41 billion.

Like most wealthy people, Terry did philanthropy, yet there has been no study into what happened to the rest of his enormous fortune. The same goes for most on the list below.

Source: William Rubenstein, The All-time Australian 200 Rich List, 2004.

The reasons behind squandered wealth

Getting back to the book and what happened to the missing billionaires, the authors point to obvious mistakes such as overly aggressive risk taking and profligate spending.

Haghani and White believe that bad investments aren’t to blame, but the concentration of risk is. Being quantitative finance guys, they call this the sizing decision – the optimal share of wealth to allocate to risk assets, or the equivalent for assessing how much to spend at intervals through time. They suggest that estimating this share is “the most critical part of investing”.

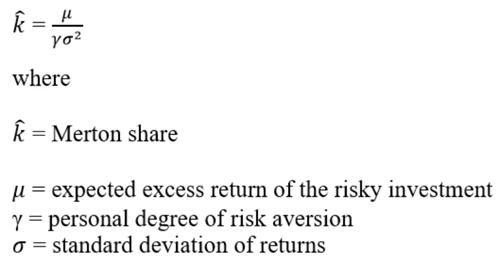

The book outlines various quantitative solutions to the investment sizing decision, starting with John von Neumann’s game theory research in the 1940s, to John Kelly’s in 1956 (the Kelly criterion) and later Robert Merton’s in 1969 (the Merton share) – the same Merton who was on LTCM’s board.

The book goes into detail on the Merton share, which has since become a cornerstone of modern portfolio design and management.

At its simplest, the Merton share formula is an elegant one:

Source: James Picerno

I won’t go into too much detail, but the authors advocate using a dynamic asset allocation to manage the risk and return of portfolios, with the Merton share as a basis.

How to preserve wealth

Unfortunately, the book devotes too much time on formulas and not enough on the practical ways that wealth is often squandered, such as:

- Taking too much risk on too few investments

- Investing in things not properly understood

- Trusting people with money that shouldn’t be trusted

- Having unrealistic expectations for returns

- Spending more than what’s earned on investments

- Divorce

What’s the answer to preserving wealth, then? A dynamic asset allocation, as the book proposes, is too complex for the average investor to implement. Luckier, there are easier, more commonsense methods that are just as useful to maintaining and growing assets. These include two things above all else:

- Diversify your investments

- Spend less than you earn on those investments

Do these things, and it’s highly unlikely that you’ll end up like the Vanderbilts and countless others.

Oh, and one other thing: if you’re lucky enough to build a substantial war chest and don’t want your children to squirrel it away, be sure to teach them how to handle money and the value of a dollar. They’ll thank you later.

James Gruber is editor of Firstlinks and Morningstar.