Unsustainably high house prices financed by extremely high levels of debt at unrealistically low interest rates presents a risk to the local banks, all of which are heavily exposed. The main problem is not in owner-occupier housing but in high-rise investment units which are over-supplied in central Brisbane, Melbourne and Perth.

Bankers will lend until their banks need to be bailed out when the music stops. With the Basel Committee slow to act globally for fear of stifling the early recovery in Europe, the local regulator, APRA, has also been reluctant to act. Banks are now required to limit investor loan growth to 10%, but this is a laughable ‘speed limit’ which is guaranteed to further inflate the bubble.

Shadow banking and the risks in low-ranking security

APRA has also requested the banks limit interest-only loans to 30% of housing lending, another ludicrously high cap. Banks have also reduced lending to high-rise developers and end investors meaning more borrowers are obtaining finance from ‘shadow banking’ sources (just as in China) via products offering high yields to unwary investors (including many thousands of SMSFs) who think they are investing in property. In reality, they are lending to property developers on unsecured or low-ranking unregistered second or third mortgages on holes in the ground.

The outcome is likely to be similar to past speculative property cycles. Oversupply will lead to rising vacancy rates, falling rents, defaults by purchasers who can’t get loans to settle, failure of over-geared property developers, bad debts for the lenders to purchasers and developers, failure of mortgage funds and consequent losses to retail investors.

When the music stops, tens of thousands of low ranking lenders to property developers will be left with nothing. The unit owners – even if they can find the money to settle the purchase – will be left with empty units or high vacancy rates and low rents for years until demand eventually catches up with supply. Unlike past booms, general price inflation will not magically lift prices and reduce the real size of the bad debts.

When developers finally get the message to stop developing new projects, rising unemployment from the collapse in construction activity will cause a wider slowdown in spending and demand. It has been 25 years since the last recession, which followed the same pattern. In the last recession, the main culprit was bad lending by banks and finance companies to commercial property developers and purchasers, but this time the focus will be on residential property developers and purchasers.

Bond spreads are not recognising the risks

Widespread negative impacts from the impending unwinding of the high-rise construction boom are probably a while away yet. Buyers are still eager to buy, with many projects selling off the plan in hours to novice ‘investors’ and speculators, and developers are still obtaining finance from non-bank sources. Many are financed directly with cash from China. The RBA is giving mixed messages about possible further rate cuts and is certainly not warning of rate hikes.

Because of the heavy reliance on housing and construction finance from local banks, and because local banks are highly reliant on foreign debt markets for funding, the local banking market (which makes up some 30% of the Australian stock market value) is extremely vulnerable to global debt markets and the global events that drive it. Credit ratings on the big local banks were downgraded in late 2011 when the RBA started cutting rates. As cracks appear in the local high rise market, global sentiment toward our local banks will sour, raising their cost of foreign debt and hitting share prices.

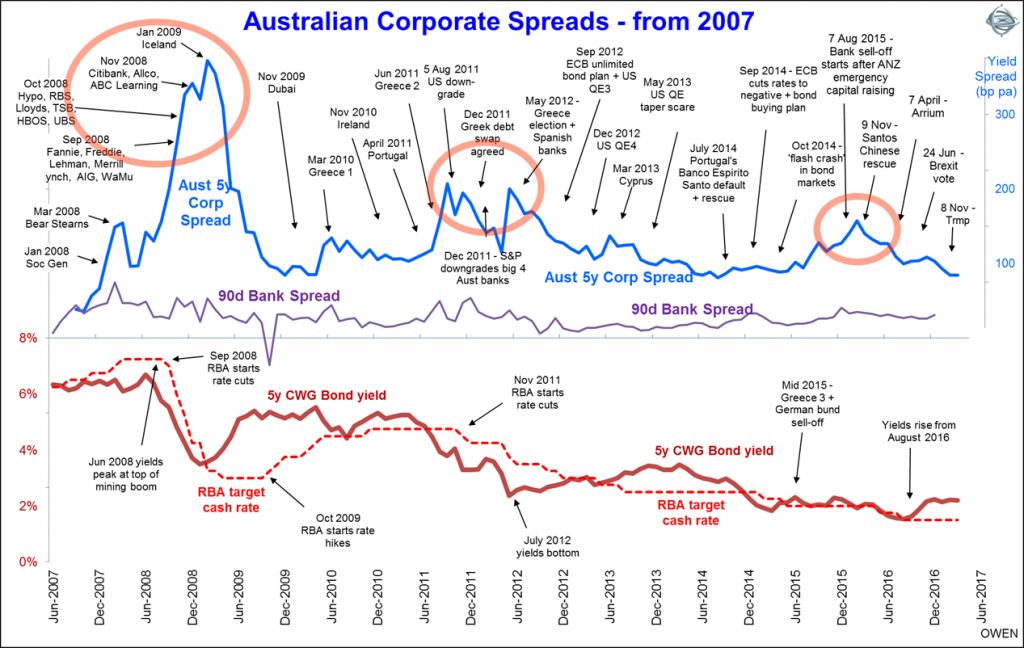

One useful barometer of market perceptions of local bank risk is credit spreads. Here's how spreads on Australian AA-rated bank senior debt have changed over the past 10 years.

(Click on image for improved viewing).

Perceived risk (and pricing for risk) for the local banks seems to have almost completely evaporated in the year since the February 2016 worries. Prices of bank shares and low ranked debt and hybrids have risen rapidly over the same period. Nobody can predict the exact timing of when sentiment will change, but eventually, complacency in portfolios will be punished.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at independent advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.