We are at a confluence of deflationary and inflationary forces. The deflationary forces of debt overhang and demography are considerable. The last 20 years in Japan illustrates that not even expansionary monetary policy can necessarily solve these problems. Yet, against that, we are in the midst of perhaps one of the greatest peacetime expansionary monetary policy experiments. This is applying significant inflationary forces to the economic environment.

When two such strong, opposing forces exist simultaneously, the net outcome is clearly uncertain but some observations can be made:

- Inflationary policies (the monetising of deficit) are popular and austerity is unpopular. In fact, monetised deficit spending is the ultimate politician’s free lunch with the largesse bestowed upon voters without the need for unpopular taxes or increases in debt.

- Deflation is not an acceptable outcome for monetary authorities. As the former US Fed Chair Ben Bernanke explained in his famous 2002 ‘helicopter’ speech, the Fed has the ability to prevent deflation, given that they have unlimited control over the money supply. Inflation is the only way indebted governments will be able to meet their obligations. This dynamic includes Australia, where government debt levels (albeit from relatively low levels) continue to rise and both major political parties have appeared to abandon serious fiscal discipline in the short-term.

These arguments imply that the final outcome of this global debt cycle should be inflationary, but it does not reveal the potential timing of this scenario. Inflation is not anticipated but prudent investors should prepare for a range of possible outcomes and interest rate scenarios.

Does inflation matter?

What would inflation mean for the Australian economy and the equity market? To answer, it helps to consider the starting point today:

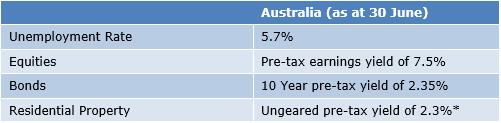

Source: UBS, Goldman Sachs, Lazard Asset Management Pacific Co. *as at 31 March 2017.

Most of the world, including Australia, has negative real policy interest rates (cash rate minus inflation) and even more negative policy rates if considered in light of central bank inflation targets. Thus, if economic conditions were to ‘normalise’, we would experience rate rises, even without any rise in inflation. The bias is clearly on the side of rates rising from current levels.

The second observation relates to the valuations of the major asset classes. Which assets are priced on negative real spot interest rates and which ones are not?

We view equities as being on the expensive side of fair value, but not dramatically so. The pre-tax earnings yield of approximately 7.5% for the S&P/ASX200 index, as at 30 June 2017 is in-line with the average over the last 20 years.

In contrast, bonds, by definition are priced on the current spot rates, with bonds yielding around 2.35%, based on the Australian Government 10-year bond yield as at 30 June 2017.

From on our assessment, Australian residential property, also priced on current spot, appears to be overvalued and has a pre-tax yield of around 2.3% according to Residex Data, as at 31 March 2017. It is clear that there are signs of speculation, including very high investor participation, and widespread interest-only borrowing in this market. The price-to-income multiple in Sydney now stands slightly above that of Tokyo in late 1989 just before the property bubble burst.

Four inflation scenarios possible

For Australia, the size of the residential property market ($7.5 trillion) and its dominance in household balance sheets make it a critical factor in assessing possible outcomes from a rise in inflation.

One would normally consider four possible growth and inflation scenarios:

- Stagflation – low growth, high inflation

- Japanese experience – low growth, low inflation

- It’s all OK – good growth, low inflation

- QE wins – good growth, high inflation.

A rise in inflation and an associated rise in interest rates would most likely result in a significant price correction within the Australian residential property market. At a cash rate of only 2.5% (up from the current level of 1.5%) for example, households would be devoting about as much to mortgage payments as they did in the late 1980s when variable mortgage rates reached the high teens. A rise of the cash rate to 5%, which is a number broadly consistent with a 2.5% inflation target and nominal growth of about 2.5%, could lead to potential wide-spread mortgage defaults.

It is likely that a rise in inflation may be followed by a recession and a return to very low inflation or deflation. Australia’s high household debt levels make the economy vulnerable to high inflation, which should be a serious concern for investors.

Potential impact on Australian equities

An inflationary environment would mean different things for different areas of the economy, especially when current starting prices for sectors are taken into account.

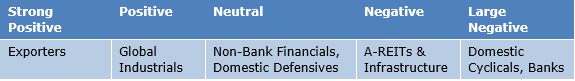

Assuming a local rise in inflation and potential recession, the biggest risk in the S&P/ASX Index appears to be in the banks and domestic cyclicals. Both industries are heavily exposed to high consumer debt levels. We believe that the biggest beneficiaries would be global exporters, who would theoretically become more competitive from a lower exchange rate and reduced wage pressures in a recession. It should be stressed that not every company in these broad groups would be affected to the same degree, as each company is different and importantly is trading on a different valuation. Security selection will remain critical, both in terms of sectors and the companies within these sectors.

High inflation: potential winners and losers

Of course, if the entire world experienced inflation, benefits to exporters would be eliminated. Yet given that Australia did not fully participate in the GFC and has much higher consumer debt levels, Australia would likely experience larger deflationary pressures. Thus, it is likely that the Australian dollar would be weak, partially offsetting the adverse impacts for global businesses and assisting exporters.

In an inflationary environment, we expect the Australian stock market to be negatively impacted, but given that it is a real asset class with a fairly reasonable starting valuation, at least in the medium term it may be a relatively better option compared with nominal bonds and residential property. While the bank and cyclical sectors together account for approximately 40% of the market, this is not a binding constraint on an active manager of equities.

Plan for inflation

“There are two kinds of forecasters: those who don’t know, and those who don’t know they don’t know.” John Kenneth Galbraith

Macroeconomic forecasts are notoriously unreliable, and what we have known about inflation has been upended in the last 20 years. So, we make no predictions about the timing of a return to inflation. Yet we still believe equity investors should consider inflation risk within an asset allocation framework. Our view is that inflation is a more a likely outcome than deflation over the long term.

Dr Phil Hofflin is Senior Analyst and Portfolio Manager at Lazard Asset Management. This content represents the views of the author. Lazard gives its investment professionals the autonomy to develop their own investment views, which may not be the same throughout the firm.