We live in tumultuous times. Economic dominance has moved from West to East, with the West in some ways still recovering from the GFC over a decade ago. We’re experiencing record low interest rates, rising world and national debt levels, trade wars, digital disruption, stagnation in wages and household incomes in developed economies, political populism overwhelming rationality and, for some major nations, the return of 1930s-style dictators.

The Ruthven Institute has looked at 10 main issues that are making headlines to find answers to their significance and impact. These are:

- The changing world order

- Debt, deficits, quantitative easing (QE) and living-beyond-our-means

- Record low interest rates, and fiscal vs monetary policy

- Overvalued share markets

- Populist politics and dictators

- Trade wars

- Digital disruption

- Enough future jobs or enough future workers

- Australia’s economy: structure and externalities

- Climate change

This article discusses the first three issues, and the full report can be obtained at the address at the end of the article.

A changing world order

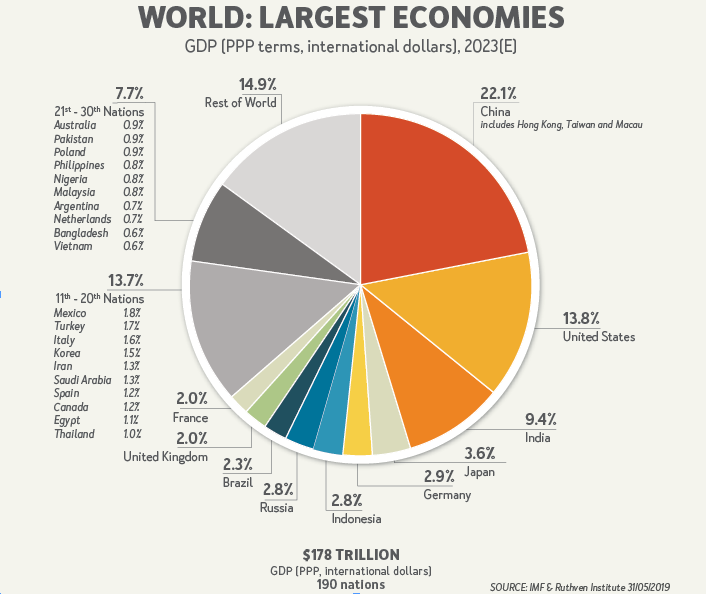

For over a century, spanning six or seven generations, the United States was the largest economy worldwide. China had previously held the position for millennia, but as a closed kingdom, few knew it was the largest. In 2016, and much to the West’s discomfort, China regained economic dominance.

The British Empire was regarded as the world leader into the 20th Century, and indeed it was if we factor in the GDP of Commonwealth countries such as India (long in the top four largest economies for centuries), Australia and others. With that hegemony came currency dominance, language dominance and a measure of stability.

But empires come and go, be they Roman, Ottoman, British or American-cum-the Western bloc. Their economies all slow due to their wealth, high standards of living, complacency and excessive regulation.

The re-emergence of China, and indeed the East at large, is pointing to a very different world order for the rest of this century and the next.

Eastern economies, especially China and India, have embraced the Industrial Age (with the advantage of advanced equipment and cheaper labour) but have equally embraced the West’s Infotronics Age of services and information and communications technology (ICT).

Australia, being a geographic, economic and social (via immigration and tourism) part of the Asian megaregion, has everything to gain from the East’s economic dominance. However, diplomacy must be carefully crafted and maintained as we morph into a larger, wealthier Eurasian society and economy. Is it possible to support both the fading West and the dominant East? We have to try.

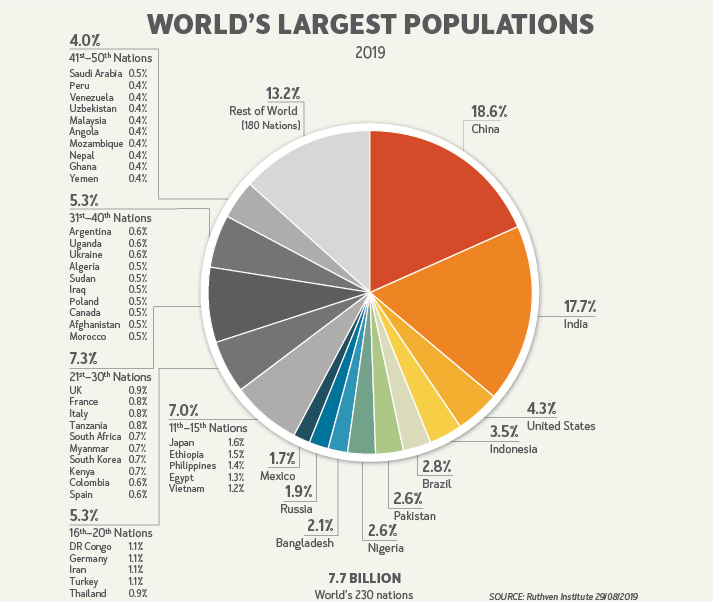

The two charts below provide perspective on current world populations and economies, as we enter the 2020s.

Tectonic changes of power are always unsettling, especially if accompanied by sabre-rattling, chest thumping and hegemony from both the old and new dominant powers – as we see happening today with territory creep in the South Seas and the world’s once-largest economy waging a trade war.

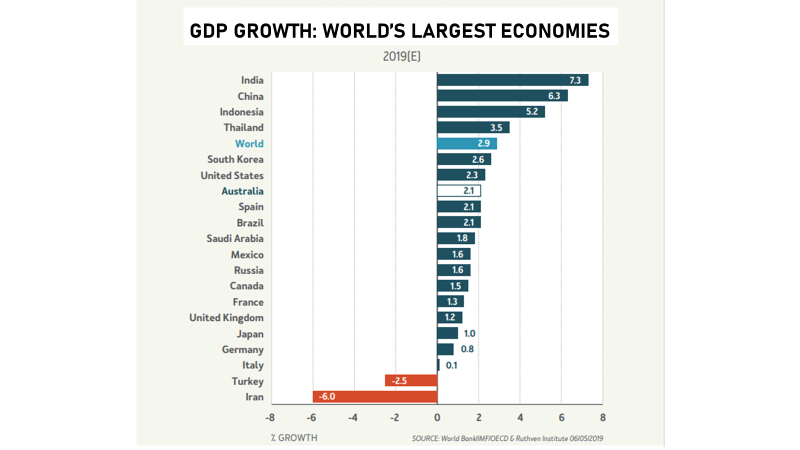

The transfer of power to China and the East at large is being expedited by slow economic growth in the West, as shown below.

Ironically, this polarisation seems not to be having an adverse effect on world growth so far. However, already the GDP (in ppp terms) of the East has overtaken that of the West in 2017, with the East growing at 5% pa compared with less than 2% for the Western nations.

Debt and deficit spending

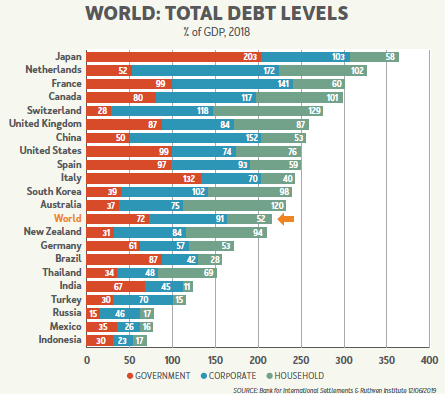

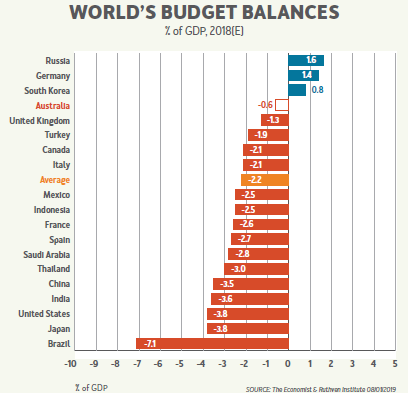

Debt levels can be worrying, as it is never wise to live beyond one’s means. The following two charts outline total debt levels and government budget balances among the world’s major economies.

More than a handful of nations have excessive debt or deficit spending risks. Interestingly, China and India are in this cohort, but Western economies are predominantly at risk. Australia is only at risk with its household debt component, but so far this has been manageable via record low interest rates … which brings us to our next topic.

Record low interest rates

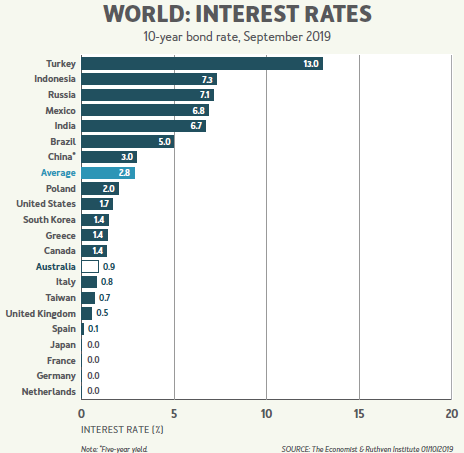

Using 10-year bond rates as the guide, the picture of interest rates is mixed across the world’s 21 largest economies, as we see below. While the average of 3% is low by historical standards, six nations are at or well above the historical average of around 5% to 6%.

The United States and 14 others are well below both the historical and current average. Turkey, Russia and Brazil have ailing economies, leading to high bond rates. However, nations with bond rates below 1% – including Australia, whose growth has dropped to half its long-term average in 2019 – are hardly vibrant, or even well, by contrast.

Continuing to lower or maintain near-zero interest rates and resorting to quantitative easing (sort of pump-priming) is, ultimately, defeatist. It frees up capital for the private sector, which may or may not invest it in growth, and increases the national debt, rather than allowing nation-building projects to proceed with government deficit spending. But again, debt servicing is easy with low interest rates, so there is no Sword of Damocles hanging over heavily indebted nations in the near future.

Australia faces this question and others as we enter the 2020s, having had no wake-up call in the form of a recession for almost three decades. Meanwhile, there have been no meaningful reforms to taxation, the labour market, energy, communications, and other aspects of the nation’s affairs since the Hawke-Keating and Howard-Costello governments ended in 2007. Monetary policy is being asked to do all the work when fiscal policy and reforms should be taking the wheel, so to speak.

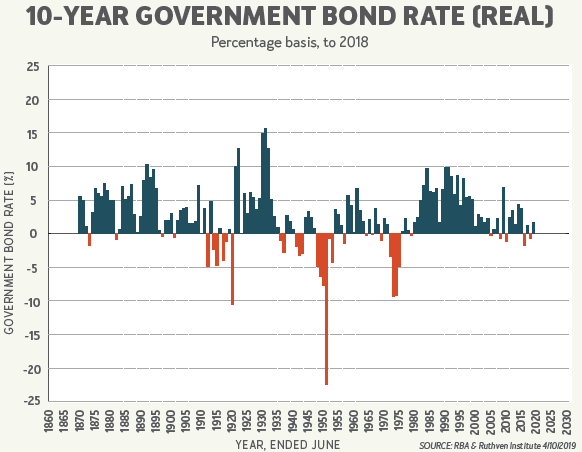

We must also ask: Do we really have record low interest rates in Australia? When we examine real interest rates after deducting inflation, we see that we do not.

It is interesting to note, over the past century and a half, the events that have triggered plunges in real interest rates. The five main periods have been:

- World War I

- The 1930s recovery from the Depression

- World War II and the subsequent years of recovery

- The Oil Crisis (and resultant inflation), and

- Now, in the years leading into the 2020s.

So, yes, low and low real interest rates are sometimes a harbinger of potentially serious problems, but they are not associated with depressions (only recovery from depressions). They seem to be more related to global traumas, such as world wars and world crises. All of which is unsettling, to say the least.

No 2020 vision to certainty

As we approach the 2020s, we are indeed sailing into uncertain waters at best, if not uncharted ones. However, we are fortunate that these times also have some historical precedents.

Australia is not over-exposed to external dangers in the years immediately ahead of us. That is not to suggest that downturns, or even a recession, are not going to happen – they could. While we certainly remain a ‘lucky’ country at large, we must not rely too heavily on our relatively good fortune to date in an increasingly volatile world. Rather, we have a serious and pressing need to tackle our internal issues, including the political hot potatoes of productivity and overdue reforms. Otherwise, the luck runs out.

Phil Ruthven is Founder of the Ruthven Institute, Founder of IBISWorld and widely-recognised as Australia’s leading futurist.

The full 30-page report, Uncharted Waters: 2020 and Beyond, is available by emailing [email protected] or see www.ruthven.institute.