Where does the US café chain Starbucks have the largest of its 28,200 company-owned and licensed outlets that are found in 76 countries? In Shanghai, China.

On 6 December 2017, as a long line of Chinese waited to be let in, Starbucks opened a 2,800-square-metre roastery in the coastal city’s retail hub that people describe as about half a football field in area. Opening the outlet proved a bonanza because the Shanghai Roastery became Starbucks’s biggest revenue earner on day one. “We shattered every sales record in the history of the company,” said Starbucks chairman Howard Schultz. Such a result explains the Starbucks ambition to nearly double the number of outlets in China from 3,200 now to 6,000 by 2022, which would entail opening more than a store a day.

Risks and opportunities for multinationals in China

Starbucks’ plans for China mimic the strategy of countless other multinationals since China modernised its economy from the late 1970s – namely, to seek a slice of the 1.4 billion strong consumer market that is growing in wealth every year. The World Economic Forum this year forecast Chinese consumption to grow 6% p.a. from 2016 to 2027, to nearly double in size to US$8.2 trillion.

China’s consumer market is expanding for two reasons. The first is that China’s economy is poised to grow at a 6% to 7% pace in coming years and will be, after India, the world’s fastest-growing major economy. The other reason is that Beijing is trying to change China’s economic model to one driven more by consumption. The results point to a surge in consumer spending power in coming years.

China’s strength comes with global political implications

China’s emergence as the world’s number two economy carries political implications that complicate the ambitions of foreign companies, especially retailers. China’s increased economic might is making the country more assertive in global politics at a time when other countries are fighting back against the loss of their global influence (in what is a zero-sum situation), especially against China’s ‘unfair’ trading practices.

Foreign businesses in China risk being stigmatised, if not targeted, amid such disputes. One of Beijing’s options is to stoke boycotts against products from a country, a frequent Chinese response to international tensions and one that predates the Communist takeover in 1949.

Boycotts are effective in China because once a country’s products are stigmatised, enduring damage is usually done to sales. Last year Beijing initiated a boycott of South Korean products after the country installed a US missile-defence system to protect itself against North Korea. The extent of product targeting included:

- Boycott of Hyundai and Kia cars

- Blocked streaming of Korean TV shows and K-pop music videos

- Near-halt of Chinese tourists to South Korea

- Forced closure of over 80 Lotte stores in China because the South Korean company handed over land for the missile shield.

The boycotts are estimated to have shaved 0.4% off South Korea’s economic growth in 2017. Foreign companies seeking to profit from China’s growing consumption must recognise that political events might harm their investments.

Political considerations have long governed foreign investment in China. Chinese consumers value global, and especially US, brands, which gives these goods some protection from Beijing-inspired boycotts. Perhaps China and other countries including the US will resolve their differences, which some days looks likelier than others. But heightened nationalism among Chinese, Beijing’s growing confidence in international affairs, and a backlash against China’s emergence as a world power, especially in the US, are global political shifts that are likely to endure. Foreign investors must allow for political risks.

The secret behind the export miracle

In 2007, China’s then Prime Minister Wen Jiabao said the country’s export- and investment-led economic model was causing “unsteady, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable” development. Beijing’s response was to shift more to personal consumption, but this new model came with challenges. The under-pricing of land and money (in the form of the exchange rate and interest rates) and cheap, labour-favoured investment over consumption had resulted in China spending about 50% of its GDP on new capital stock. At the same time, personal consumption only stood at about 35% of GDP compared with 50% to about 66% of output for most advanced economies. A cheap yuan made imports expensive for consumers while it helped exporters. Low interest rates cheated household savers of income while governments and enterprises enjoyed subsidised loans. Land grabbed for factories left peasant farmers impoverished while supressing production costs. Low wages gave people less money to spend while they reduced manufacturing costs. The result was a massive trade surplus, especially with the US.

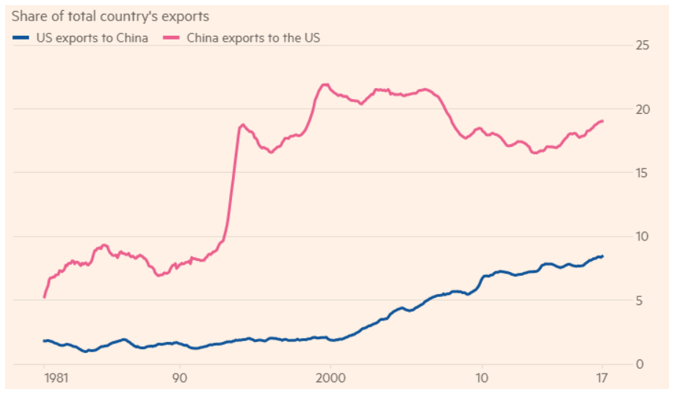

China-US goods trade relationship since 1981

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream/Financial Times

A paradigm shift by boosting wages

Untangling the under-pricing of land and money while boosting wages was a risky step for Beijing because it heightened the risk of an economic slump. Policymakers needed to set GDP growth at a slower pace than consumption growth to enable consumer spending to become a bigger part of output. By allowing the yuan to move closer to its market value, liberalising many interest rates, boosting wages and compensating farmers for lost land and livelihood, Beijing has met this challenge.

Household spending has now become a bigger driver of the economy while growth has been maintained at about 7% p.a., even if policymakers relied on an increase in debt the equivalent of China’s GDP to achieve this feat.

The World Bank readings of China’s economy show household consumption has risen to 39% of GDP in 2016 from a record low of 35.8% in 2007. Perhaps a better way to highlight consumption’s growing importance is that since the start of 2016, household spending, on average, has propelled 65% of China’s growth each quarter.

What may the future hold?

For China, boycotts hold advantages over the other options. They are easy to orchestrate via social media while Beijing can hide its meddling. Boycotts appeal to the growing nationalism among Chinese that Beijing is stoking. Victim companies can only respond by applying political pressure at home to resolve whatever issue is angering China.

But boycotts carry risks for Beijing too. The first is that other countries retaliate like they would with tariffs. Another is that foreign companies might freeze expansion plans and shut off a source of innovation for China. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese are estimated to work for the companies of any one foreign country and they might resent any loss of income. Far more numerous (and so a bigger political concern) are Chinese consumers who respect foreign brands. Chinese shoppers might resent being told to avoid foreign brands and could ignore government sanctions against Nike runners and Apple iPhones.

The full version of this article is available here.

Michael Collins is an Investment Specialist at Magellan Asset Management. This article is general information only, not investment advice.

Magellan is a sponsor of Cuffelinks. For more articles and papers from Magellan, please click here.