My father would be turning in his grave.

Jack grew up in Birdsville, served in WW2 and settled down in suburban Melbourne to raise a family, supporting us by his work as a carpenter. He was big on social equity, having a go, and the government’s responsibility to ensure everyone got a fair go.

So what would he make of the recent Intergenerational Report (IGR)? I suspect he’d see straight through the smoke and mirrors and call it for what it is. A portrait of a retrograde step for the vast majority of older Australians.

How we got here

How is it a retrograde step? First some background.

At this year’s National Press Club launch of the 2023 IGR, both ABC political journalist Laura Tingle and The Conversation’s Peter Martin made joking references to the fact that they had been around way back in 2002 when the first of the series of IGRs was released. I was reporting on retirement income way back then as well.

Let’s face it, regardless of your politics, the establishment of the first IGR was a visionary initiative by the then Treasurer Peter Costello. Such long-term thinking was unusual in Australia and badly needed, but few understood that before the first report was released. Since then, subsequent IGRs have succeeded in informing us of the key indicators we need to make a judgement whether the Australian economy is future fit across the next 40 years.

Most of the IGRs have been sincere attempts to project those future trends which will have the highest impact on the Australian economy. Despite a couple of more overtly political versions, including an at times seemingly willful refusal to even countenance the effect of climate change, the IGRs provide analysis based on statistics which allow us to future gaze and make useful policy changes to meet that future. They often also spark useful debate.

And that has happened at high volume this year. I don’t recall any previous IGR being so selectively leaked in advance, nor receiving such ongoing coverage in mainstream media. That’s a good thing as the major changes needed to shore up our budgets will need popular buy-in.

But this article is not about the five key aspects in the 2023 IGR – namely population ageing, digital and data technology, climate change, increased demand for care and support services and an increased geopolitical risk and fragmentation.

My interest is in exploring the predictions of the sustainability of our retirement income system.

The super sleight of hand

And here’s where I believe we are victims of a certain sleight of hand. If we listen to the words of Treasurer Jim Chalmers and read the summary both in the IGR and media commentary, we can all relax: retirement income is AOK.

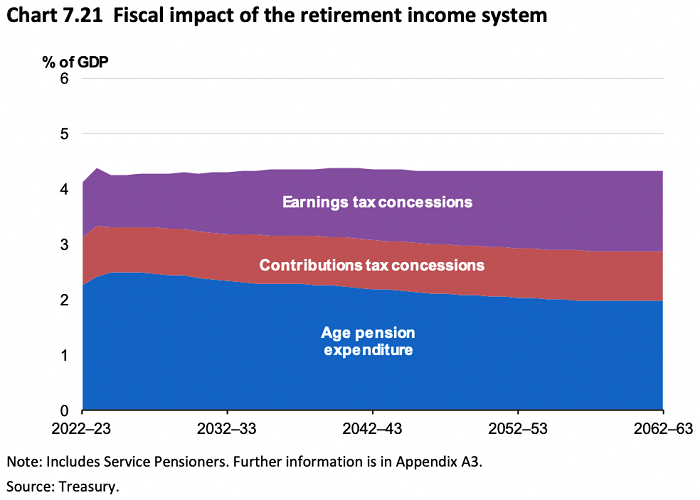

That view is based upon a graph which shows the percentage of GDP needed to fund the Age Pension gradually decreasing (from 2.3% of GDP 2022-23 to 2.0% 2062-63). This will happen while total super balances rise over the same 40 year period, from 116% of GDP to a whopping 218%.

And that, of course, leads to statements by the Treasurer that ‘super is delivering on its promise, providing a better retirement for more Australians …’

And headlines such as that in The Australian Financial Review, where super is portrayed as a ‘saviour’ by Phillip Coorey when he declares: ‘Super to ease Age Pension budget burden over next 40 years.’.

But hang on a minute.

The concessions on super (contributions and earnings) are set to increase from 1.9% of GDP 2022-23 to 2.4% in 2062-63. These concessions, as has been predicted by the Australian Institute, will overtake the cost of the Age Pension in the 2040s.

Let’s think about this. Australia already has one of the lowest outlays on its Age Pension (as a proportion of GDP) in the OECD. This is set to reduce even more as super will ‘pick up the slack’. But what will actually happen is that we will spend more on supporting super than on the Age Pension.

Favouring those with more super

Super has worked well but it is far from equitable. The mandated contribution (currently 11%) is calculated as a proportion of wages or salaries. If you earn $50,000 per annum, the contribution is $5,500 per annum. If you earn $200,000 per annum, the yearly contribution will be a minimum of $22,000. Why a minimum? Because unlike your neighbour on $50,000, you will probably have enough discretionary income to consider salary sacrifice contributions.

And you’ll thereby enjoy further benefits from concessions along the way. In the world of super concessions, the more you have, the more you get. Yes, there has been an attempt to cap some of this largesse with the March 2023 ‘Better Targeted Superannuation Concessions’ increase with an additional 15% tax on balances over $3 million, but this is nibbling at the edges.

Meanwhile the base rate of the Age Pension has not been adjusted since the Rudd Government legislated a $30 increase in 2009, some 15 years ago (it's still gone up via indexation). Those on a full Age Pension who rent have been living well below the poverty line for years. Given the current 10% year-on-year increase in rents, their situation is worsening. The rapid increase in homelessness for women aged 55 or over is uncomfortable evidence of this lack of basic shelter.

Yet the Australia Institute reports that the top 20% of earners receive 50% of the benefits of super concessions, with men receiving 71.6% of these benefits.

Put simply, the gap between rich and poor in Australia continues to widen. This is then exacerbated by a fundamentally skewed system of reward for higher super balances in retirement.

I doubt Jack would have seen this as fair go at all.

Kaye Fallick is Founder of STAYINGconnected website and SuperConnected enews. She has been a commentator on retirement income and ageing demographics since 1999. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any person.