Ok, I am pretty sure today’s post will be controversial, so I have already put on my Kevlar suit to protect me against the inevitable comments I will get from readers about this one. Because I am going to talk about taxes.

Look, I work in finance, and you can only get a job in finance if you commit yourself to being a low-tax advocate always and everywhere. And I get it. I don’t like to pay taxes and a government that taxes its businesses and citizens too much will inevitably ruin the economy and the country.

But in my view, the fetish of low taxes has gone too far, in particular in the Anglo-Saxon world (he says and immediately ducks behind a wall…).

Ever since the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions in the 1980 the standard answer of business leaders and investors to any problem has been: we need to cut taxes to get people to invest and boost growth.

For 40 years, the beast that is the government has been starved in the name of fighting bureaucracy and regulation and what has been the result: Governments continued to regulate and create more bureaucracy but cut back on investments in infrastructure, healthcare, and education so that today, productivity is declining, and the very foundations of economic activity are cracking. Maybe it is time to admit that cutting taxes is not always the best idea and that sometimes we have to increase taxes to invest in infrastructure or teach workers the necessary skills for today’s economy.

Also, in their dogmatic belief in lower taxes, most business leaders and investors seem to be impervious to the empirical evidence about the link between taxes and profits or economic growth.

Some time ago, I showed why cutting taxes for businesses does not increase corporate profits. Indeed, there is no correlation between changes in corporate tax rates and changes in corporate profits. I encourage all my readers to read this analysis here, where I explain why this is the case and why changing corporate tax rates amounts to nothing more than a redistribution of corporate profits from one set of companies to another.

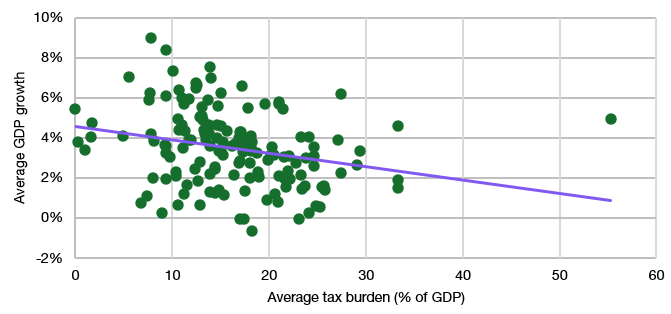

But taxes aren’t just applied to corporations. They are everywhere. Advocates for lower taxes tend to show a chart like the one below.

The chart shows the average tax burden (tax/GDP) over the last 20 years vs. the average annual real GDP growth at the same time for 150 countries. As you can see, countries with a lower tax burden on average have a higher GDP growth. A 10-percentage point increase in the tax burden typically reduces annual GDP growth by 0.7% per year.

The correlation between tax burden and GDP growth 2003 to 2022

Source: World Bank

Not so fast. The chart above is an exercise in comparing apples with oranges. Because if you create a chart with 150 countries, the sample contains very different countries indeed.

I am concerned with highly developed countries like the US or the UK, not emerging economies that naturally have higher growth rates than more developed ones.

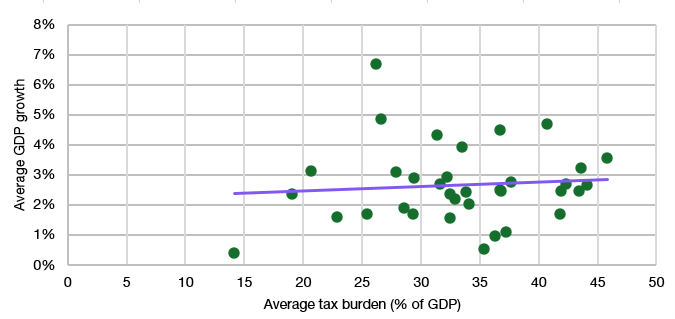

So, let’s look at the same chart and restrict our sample to developed countries that are members of the OECD. Here is what the chart looks like when we constrain our sample to a more homogeneous list of countries that are representative of what is going on in the US or the UK.

The correlation between tax burden and GDP growth in OECD countries

Source: OECD

Oops. All of a sudden there is no correlation between tax burden and GDP growth.

In developed countries in Europe, North America, and the Pacific region, the tax burden does not influence GDP growth. For every country with a low tax burden and high growth like the US or Ireland, we can find another country like Sweden or Austria with a high tax burden and a similar growth rate.

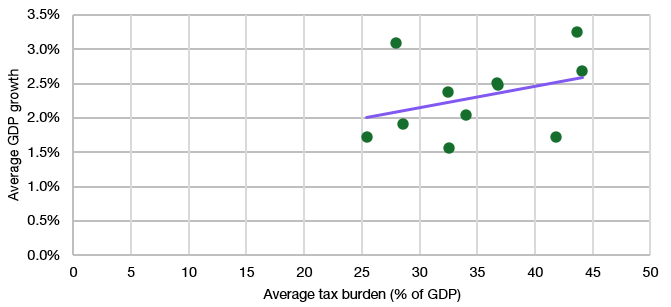

Even better, if I remove small countries like Austria or Ireland and only look at the 10 largest developed economies in the world, I get the following relationship.

The correlation between tax burden and GDP growth in the 10 largest developed countries

Source: OECD

So, in the largest, most developed countries, a 10-percentage point increase in the tax burden on average leads to a boost of annual real GDP growth of 0.3%. Huh?

In short, there is no simple or reliable relationship between the tax burden in a country and its economic growth. As always, it is far more complicated than just lower taxes = higher growth.

It essentially depends on what is taxed and how the money that is raised from taxes is spent. Which brings me to fiscal multipliers.

Fiscal multipliers measure how much output changes for every Dollar/Euro/Sterling of taxes raised. The table below shows the fiscal multipliers the CBO uses in the US to score proposed laws.

For example, if the US government increases personal income tax, then for every Dollar raised in additional taxes the GDP shrinks by 0.1 to 1.5 Dollars with a mid-point estimate of 0.8 Dollars. How much output will suffer from higher taxes depends on the state of the economy. In a recession or a weak growth environment, tax hikes hurt much more than in a strong economy.

So, hiking taxes is bad for growth. But what does the government do with the money? If they just spend it on wasteful activities like increasing the bureaucracy it is unlikely to generate more growth and the net effect of tax hikes is a loss of output.

But if the government invests in infrastructure, it tends to generate 0.7 to 2.2 dollars for every Dollar spent. If the government increases aid for the unemployed, every Dollar spent increases economic output by 0.7 to 1.9 Dollars. If you net it out, an increase in income taxes to spend on infrastructure gives a net boost to GDP of 0.5 Dollars for every Dollar raised in additional taxes.

This is the flaw with the argument that a small government is a better government with less wasteful spending. Every government, no matter how large or small, is subject to lobbying and has certain spending needs it cannot cut. The result is that if a government is starved from its tax revenues it will typically not cut the waste, but the stuff that is easiest to cut. And that often is spending on infrastructure (that road will do another year), or education (what’s the difference between the average class size of 20 pupils vs. 25 pupils?), etc.

So, instead of being so incredibly fixated on cutting taxes, business leaders and investors alike should focus more on how tax revenues are used.

PS: One country where this link between taxes revenues and government spending is made very explicit is Switzerland where tax increases tend to end up before the people in a referendum. And Swiss people will vote for higher taxes if you can explain to them what you need the money for. I know, crazy.

Note: This article was part of a series. Please see the explainer to this series at the start of the first instalment.

Joachim Klement is an investment strategist based in London. This article contains the opinion of the author. As such, it should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of the author’s employer. Republished with permission from Klement on Investing.