"For a premium, a title may be insured with a title insurance company, the very existence of which is surely no compliment to our present system" - Charles Alfred Patterson, 1938

“Since the distribution and protection of land is generally held to be a natural function of the State, why can not the guarantee of title also be included as a natural function in the protection of land? - Charles Alfred Patterson, 1938

I’ve recently arrived home from a two-week holiday in Japan. During the flight home I stumbled across Tokyo Swindlers. It’s a show about scammers who pose as land sellers and trick buyers into paying large sums of money for land in Tokyo that buyers can never register as their own with official land registers.

I also recently listened to the Planet Money podcast explaining a case of identify fraud and the role of titles insurance in such matters. These events led me to ponder the world outside of Australia’s Torrens title property system.

Although we talk a lot about property investment and homeownership, Australians don’t think much about the system of property titles itself — how claims of ownership operate, how much the system costs, and how this matters for risks involved in buying and selling property.

That’s because Torrens title makes things easy.

I was initially astonished that such cumbersome property dealings exist in modern economies like Japan and the United States in 2025. Property buyers in Japan can be swindled out of billions of yen, while Americans spend over US$20 billion annually on title insurance. This is unnecessary in Australia because of Torrens title.

In this article, I indulge my curiosity triggered by these events and contemplate some big economic questions around the issue of title security, transaction risk and cost between Australia’s system and the alternatives abroad. I then muse about why the revolutionary Torrens title system, an Australian invention from the 1850s, has not caught on more widely.

Before we dig in, here’s a quick overview of what I have learnt about property titles in Japan and the United States compared to Australia:

- In Japan, there isn’t a title insurance market, and buyers often risk billions of yen paying a seller BEFORE they are guaranteed ownership. Buyers reduce their risks by doing extensive identity checks, but this still leaves open the gate for identity-thieving swindlers.

- In the US, the deed system provides no guarantee of ownership after a property purchase. All dealings with a property (inheritance claims, mortgages, etc.) happen independently of any central authority. Risks from previous parties making a claim against a purchased property have fostered a title insurance market that resolves losses for buyers in the case of disputed ownership claims or other errors.

- In Australia, the Torrens title system keeps an indefeasible record of all property and dealings with the property, and the Titles Office is hence a party to all transactions. As the final record keeper, it resolves almost all risks hence there is no need for a title insurance market, nor extensive identity checks by buyers (identity checks happen on the seller side of its relationship with the titles office).

Torrens titles versus deed-based property

Torrens title is named after South Australian governor Sir Robert Torrens, who first implemented this system of property record keeping and public guarantees in South Australia in 1858.

Source: Wikipedia

The basic idea is that since the government is in the business of protecting property rights, it should at least be the final record keeper of who has those property rights.

Under previous deed-based systems, a transfer of property ownership happens independently of any public authority by way of a deed, which is just a type of contract specific to property transfers.

Mortgagees would also make claims over property with another type of contract, a mortgage deed. Historically, there was no requirement to collect and store those deeds anywhere, but generally, there are registrars who collect local deeds and try to build up records of property dealings.

The problem in colonial Australia was this: people could buy property from a seller with no verification that the lot, the street, or anything else was actually real. Many frauds and swindles happened and relatively few risk-takers entered into property trades.

Robert Torrens’ experience in trading ships led him to realise there was a better way.

At the time, registration of all ships over 15 tons at their home port was compulsory, and the port/customs authority was required to record all ownership records and transactions of those registered ships. Doing so created a verifiable record of ownership for any parties involved in the trade of merchant vessels.

Torrens campaigned for the South Australian parliament on the idea that States should do the same for land, creating a database to collate all current claims and be the indisputable record of all transactions, encumbrances (mortgages and easements) and dealing. The state should itself guarantee this record, making it indefeasible.

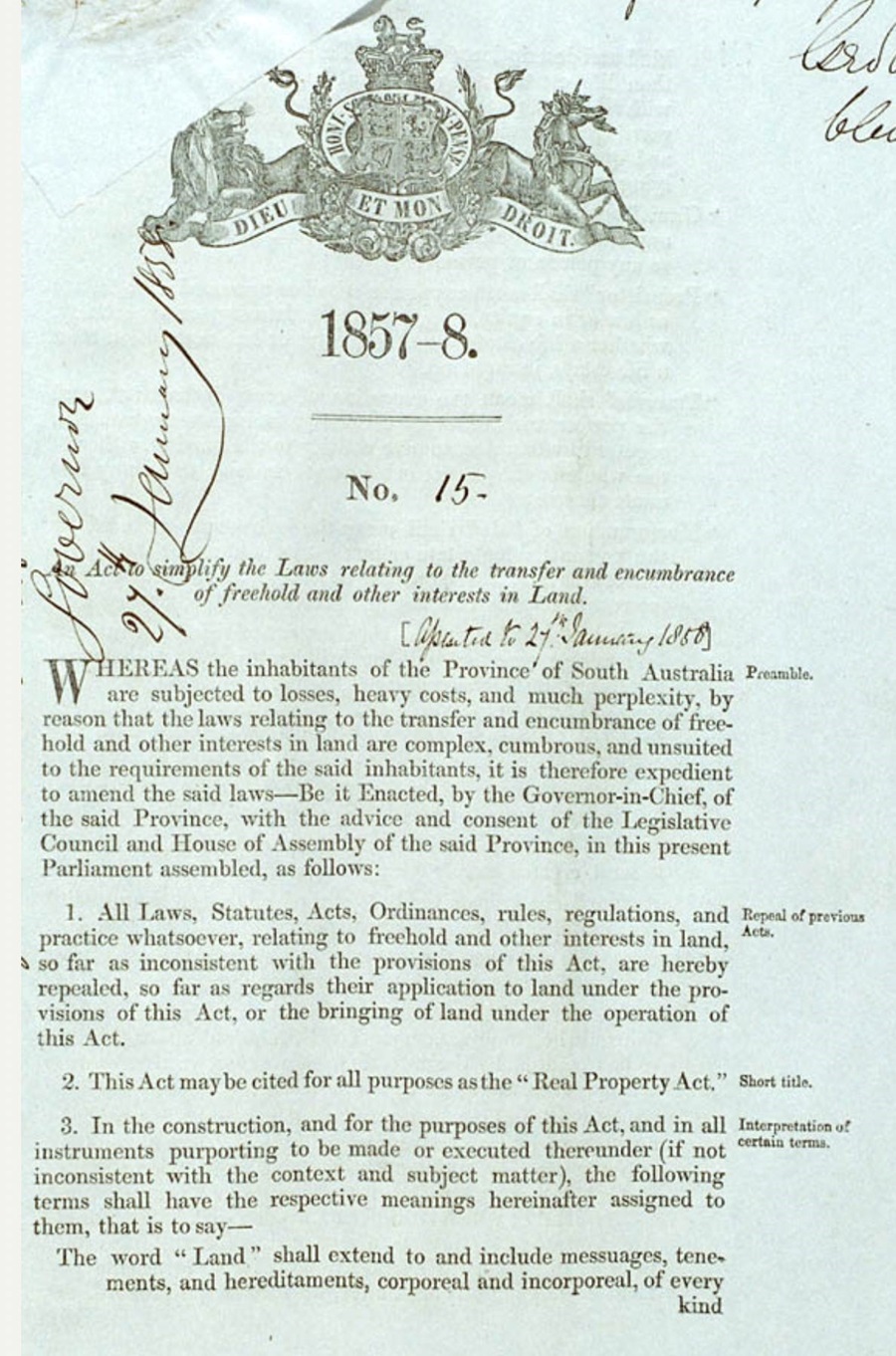

Torrens was elected to the South Australian Parliament in 1857 and the Real Property Act 1858 was passed to “simplify the laws relating to the transfer and encumbrance of freehold and other interests in Land”. Other states soon adopted Torrens title systems: Queensland in 1861, Victoria in 1862, and New South Wales in 1863.

The original Real Property Act 1958 that Torrens created for South Australia

Comparison of risks and costs of titles versus deeds

A major risk that a deed-based system could not overcome were claims against a new owner of a property of which they were unaware. For example, consider the diagram below that tracks interests in property over time as a property is transferred from Owner A to B, to C and finally to Owner D.

Owner A sells to Owner B. But Owner B takes a mortgage. When they die, the property is transferred to one of their heirs, Owner C. But there is a competing potential claim on the property from an alternative heir.

Regardless, the first heir (Owner C) then sells the property to Owner D. The competing heir may go looking for their rightful inheritance, and Owner D will be the one who loses out if that claim is successful.

New property owners take on risks of historical claims to the property, such as unknown mortgages, liens of debt secured against the property, easements, claims by heirs and more. Exactly the problems Torrens was trying to solve.

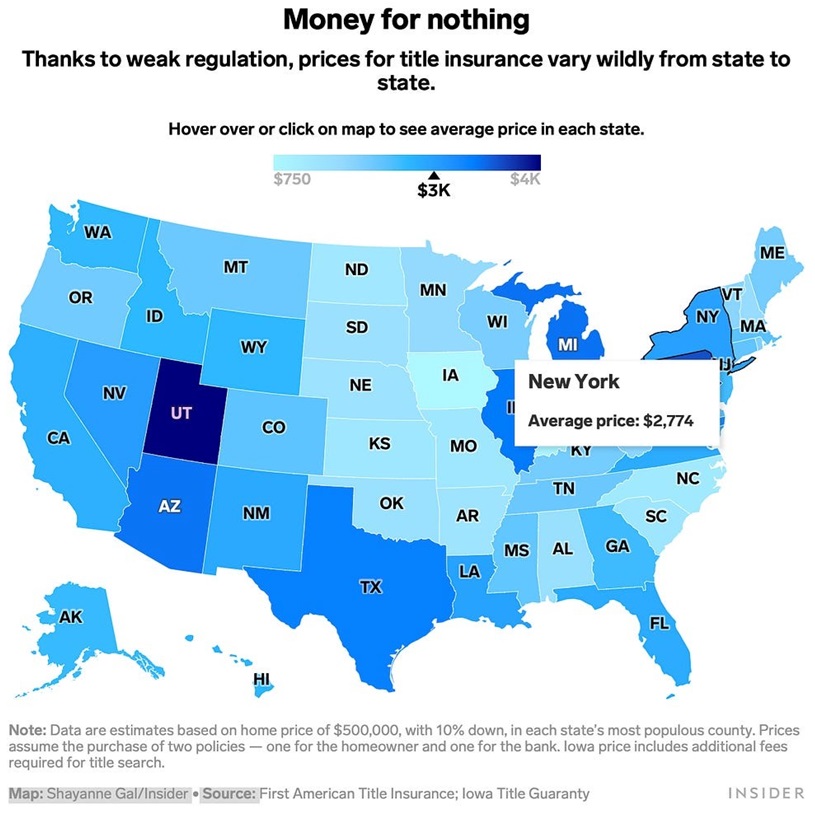

In the United States, title insurance is bought by the buyer during real estate transactions to cover any loss if they later discover that they haven’t bought the free and clear property they intended. Title insurance usually costs about 0.5% of the purchase price of a house (see below image), which adds up to over US$20 billion per year.

The substantial costs of title insurance across the United States

Not only do I think that the whole title insurance industry should not exist at all, it seems that in the United States, it is plagued by undisclosed kickbacks and commissions that end up costing buyers thousands more than is necessary.

You can tell there are some dodgy things happening because these firms work hard to market their credibility and do this by adopting names and logos that just ooze trustworthiness like First American and Old Republic.

I’m not alone in thinking there is something dodgy about this industry:

I find it even more strange that Kurt Pfotenhauer, the vice chairman of First American Title Insurance Company, suggests that the only real benefit of the United States system of deeds that generates the need for title insurance is the speed of transactions.

Yet exactly the opposite was the reason behind the introduction of Torrens title – the indefeasible nature of state title records makes it easy for various parties in each transaction to get the information they need quickly and proceed.

This multi-party settlement process is now done electronically in all states via an app called PEXA, which was created as a public-private company to compensate states for contributing their intellectual property.

Simple property deals in Australia today can settle in as little as two weeks, with the process being so simple that with relatively small fees for property transactions, each state’s Titles Office makes a huge profit.

If Australians paid as much title insurance as the United States, we would be forking out about AUD$2 billion per year, while the operation of the Torrens title system costs about 10% of that amount.

With all these clear benefits of derisking and streamlining property transfers, one might ask why, in the 167 years since Torrens, the system is not the global norm.

Why did Torrens title systems fail elsewhere?

There are clear efficiency gains from a Torrens title system when every property in a state uses it. It is therefore puzzling that many states in the United States attempted to adopt a Torrens title system but later repealed it.

Some might have philosophical issues with the fact that the state is directly a party to all property transactions, but this is all semantics. The state is a party indirectly in every situation, so why not make it explicit and derisk the process at the same time?

An interesting 1938 analysis (here) explains some reasons for why Torrens title was not more widely adopted at that time. All objections to Torrens law stem from either: (1) ignorance of its merits, or (2) self-interest (p78).

One influential and self-interested group is the title insurance companies themselves, who could see billions in profits disappear. Hence, they argue that modern title insurance is a more efficient way to deal with the problems of the deeds-based system, even though it costs an order of magnitude more than the alternative.

However, most U.S. states failed in their Torrens title adoption because of a lack of compulsion—an owner could nominate their property into the Torrens title system or choose to stay outside of the system.

Since for any one transaction the costs are higher to get into the Torrens title system than transfer a deed, every party to each transaction has an individual incentive to avoid these initial costs. The only savings are for future parties, not them.

The trouble with weaning property off older deeds-based systems is also why England and Wales took so long to adjust to a Torrens title system. It took until the 1990s to require registration of all lands, completing a 130-year process.

So what?

Far from an outdated relic, Torrens title appears to be the revolutionary, cheap, low-risk way to handle property dealings. Sure, there are still occasional identity fraud cases. But no system is perfect, even if it can save billions per year and reduce risks.

The costs of change, which include creating politically influential losers, suggests that if a place has not yet adopted the Torrens title system, it is unlikely to do so now. Unless, that is, the costs of maintaining the old system become obvious enough to stimulate political pressure.

Dr Cameron K. Murray is Chief Economist at Fresh Economic Thinking. The original article can be found here. Subscribe to his written work at Fresheconomicthinking.substack.com. This article is general information.