In late September 2022, CEO and Co-CIO of Platinum, Andrew Clifford, sat down with Investment Specialist Julian McCormack to discuss interest rates, inflation, China and Europe. This is an edited transcript.

JM: There is a lot going on in the markets. Let’s start with interest rates, how far will they go?

AC: The typical approach to answering this is to examine the underlying components of inflation and where they're heading. There is a lot of evidence indicating that inflation is starting to peak, although one thing that is holding up is the employment market. But at some point, inflation will roll over. I think the bigger issue here is how much interest rates have moved already. We've just been through one of the most extraordinary increases in interest rates. Coming off near-zero rates, yields on two-year US Treasuries are now around 4% and 10-year yields aren’t far behind. These are levels we haven't seen since 2008.

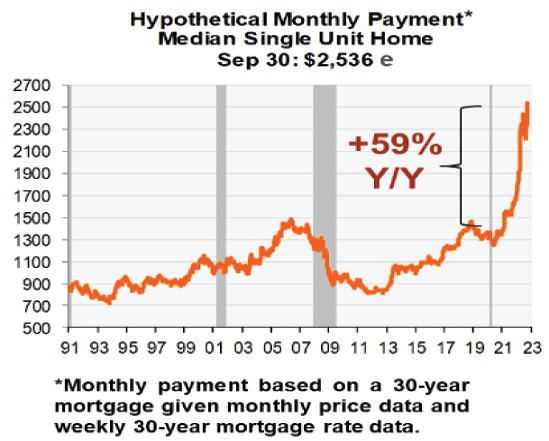

When that degree of change in funding costs occurs in the economy, we must expect some fall-out. In the US, average monthly payments on a new mortgage for a median-priced house are up around 60% from a year ago, they have almost doubled from the pre-COVID period, and are up threefold from the lows of 2013/2014 (see below). US households predominantly have fixed-rate 30-year mortgages, so they obviously aren’t actually paying the higher payments, but provides a real sense of just how much funding costs have changed, and it's not surprising to see activity in the US housing market in free fall. We need to turn our minds to the damage in the economy. I think what we have ahead of us is a very difficult period for company earnings across the board.

US Monthly Mortgage Payments

Source: Piper Sandler.

JM: If you're the US Federal Reserve, do you pause, keep raising, or cut?

AC:. It’s not really a question for us as investors of what they should do, it’s simply just a question of what they will do. Two or three years ago, when central banks were saying rates would be zero until 2024, I said, “Well, you shouldn't believe that”. They tell us that because they need to build expectations in. They want you to believe it, so whether you're a consumer or a business, you will act as if rates are going to stay very low.

Similarly, today they have to say rates are going up and build that same expectation. While they might slow the frequency and size of the rate increases, which will, of course, come to an end at some point, I think we're a long way away from seeing dramatic cuts in rates. There is a real risk that if the Fed cuts rates too quickly, with those strong employment numbers and inflation still well ahead of interest rates, that they will reignite those inflationary forces.

JM: What could come out of left field in terms of monetary policy or its reformulation that could really change things?

AC: What I'd say, which is not answering your question directly, is that we've acted for a long time as if there are no limitations on the actions of governments. But the real economy, which is labour, people going to work, and the capital they use, is the real limitation on the economy. All governments are doing is redistributing funds and resources around the economy, and there are limitations on what they can do.

We had a great example recently in the UK where the market didn’t respond well to the UK Government’s proposed £45 billion mini-budget, comprising unfunded tax cuts and temporary measures to help with energy bills. The market said there is no way they are doing that, because simply, it requires the rest of the economy and the world to fund that decision and the government subsequently backtracked. Inflation is telling us that we've come up against the limitations of how governments can spend.

JM: Let's go to the opposite extreme. How would you characterise China’s situation and outlook given its last 40 years of economic history?

AC: There are a few questions we need to address around China, but I'll start with the simple economic one; the country is in a recession. Whatever the numbers say, this is the most serious downturn in growth since the economy opened up. At the centre of that downturn is a collapse in sales of new properties that is flowing through to construction and activity. This is a very important part of the Chinese economy and the collapse in volumes has come about as a result of policies designed to cap property prices. It's been a severe policy error that has destroyed households’ confidence in the property market and property developers.

The idea, though, that some great property bubble has popped is not really on the mark. They have not delivered nearly the amount of modern housing stock that the Chinese population needs. They have a problem. It's like a liquidity trap. Nobody wants to buy a property because they don't know if the developer is going to honour their commitment to develop the property. Confidence needs to be restored. Rescue funds are being provided to the developers, not to get those developers back on their feet, but to ensure that these half-finished developments go ahead and are completed. I believe they're heading in the right direction on this front, and if they fix that problem, I think that will solve the economic slowdown there. Property sales may not get back to the huge levels they were at, but they will most likely recover.

Of course, China has also had a resurgence in COVID, but we know that countries exposed to COVID get through it, one way or another. I'd be surprised if we weren't moving on shortly from that in China. We are also seeing lots of stimulatory actions. Monetary growth in China, for instance, is now accelerating and at the highest levels for quite a few years.

In sum, we are optimistic that China will come out of this recession, just as we would be for any normal functioning economy coming back from a downturn.

The bigger issue with China is the political tensions with the West. My first response to this is always the same: our systems are so intertwined that for either side to ignore that would have significant implications economically, not just for China, but for the world. We can't predict the outcome; however, we would hope that good judgement prevails on both sides. When it comes to questions like an invasion of Taiwan, I think there is a lot of focus on the unlikely possibility of that occurring rather than the things that might really happen.

The US security agencies that said Russia would invade Ukraine are saying right now that an invasion of Taiwan is highly unlikely and that there are no such preparations. It's more the middle ground where things can really hurt individual companies and portfolios, such as sanctions, for example. Recently, the US imposed sanctions preventing NVIDIA from selling some of its high-end graphic processing units (GPUs) to Chinese customers, which is damaging to its business. As investors, we need to be aware of the risks and ensure that we're not overly exposed.

JM: Moving onto Europe, the outlook there is gloomy. How are you framing the extremely weak consumer confidence, the industrial slowdown, and the vulnerability around energy, versus what is generally a pretty good jurisdiction?

AC: Obviously, the war has had huge humanitarian costs not just in Ukraine but across Africa in terms of food supplies. However, if we just focus on the economic and investment implications, one of the biggest impacts is on the cost of energy. Companies across the board have seen a substantial loss in their competitive positions due to the higher energy prices, and we've certainly seen closures in capacity of fertiliser and chemical plants and the like.

On the other hand, this has also been reflected in a weaker euro. We've obviously seen very dramatic strength in the US dollar versus all currencies, not just the euro, including the Australian dollar and the yen. There's a slightly different story for each, but it's mainly a US dollar story, which benefits the rest of the world in terms of their competitive positions. For Europe, the fall in the euro has helped to level out the impact of the higher energy costs on industrial companies and restore profitability.

The unknown question is how long energy prices will stay at this level. I would expect that over a two-to-three-year period, the intense pain Europe is feeling now will ultimately dissipate as new sources of energy are secured. We have already seen Europe manage to secure a significant increase in LNG imports and the like.

JM: American corporations, which have enjoyed some measure of global dominance, have the reverse problem with respect to the currency impact on revenues. How are you thinking about these headwinds?

AC: You would expect a lot of concern about earnings for US companies, based just on the strength of the US dollar. There's some talk about that, but not a lot. So, the market reaction has been different to what we would have seen in earlier times. I think this reaction partly reflects an aversion to business and geopolitical risk, but there's also recency bias at play here, where we remember what worked well before. It’s also worth noting that the US market was the most pumped up by monetary expansion, and while that's certainly faded, it's still benefiting from the tail-end of that, which is holding up US asset prices.

It's been a really interesting market this year. In one way, there has been a stealth bear market for a number of years now for anything that’s not in the ‘growth’ or ‘defensive’ camp. Their valuations have been continually marked down. When we entered this year, the world was looking like a pretty good place, so you would have expected economically exposed or cyclical companies to do well.

However, we then had the extension of the recession in China due to a resurgence in COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As a result, companies that didn’t meet those pure safety criteria have taken big hits, falling to crisis-level valuations - to levels that we saw at the bottom of 2009 - whereas the fade in glory of the great tech stocks is slow. We also saw this happen in 2001. It took a very long time for the likes of Oracle, Cisco, Dell, EMC, and Microsoft to reach their lows in both share prices and valuations, but they all ultimately fell to price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples of 10, having been at 50, 60, or 70.

It will all depend on the earnings that companies deliver, because expectations are very high. The stock that has most severely disappointed investors to date is Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook), followed by Netflix in that group. Meanwhile, Google is an advertising business, and interest rates are rising a lot. I would be thinking seriously about how earnings are going to unfold for that business in the next couple of years.

JM: People are quite obsessed with picking the bottom of markets. Going back to your initial point on interest rates, how much lower can US markets go? Or where are we in the market cycle?

AC: I think the best we can do is to look to history for a guide. We had an extraordinarily speculative bull market, particularly for companies with questionable business models with no earnings, or at the extreme, meme stocks like GameStop and so forth. This was driven by a huge torrent of money thrown at it by various policies that were put in place. Your natural inclination, given that the ‘liquidity tap’ has now been effectively turned off, is that this is going to be a pretty bad bear market.

In the bear markets of 2000-2003 and 2007-2009, indices fell around 50%. I'm not sure why people are thinking it's going to be a lot different this time. Having said that, though, there are opportunities out there now as many stocks are already down 50-60% or more. Some of those are stable businesses sitting on nice earnings multiples, such as semiconductors and auto companies.

There are some pretty interesting assets out there, but growth and tech stocks have yet to adjust. People have also been hiding in a whole range of other more boring things lately, such as consumer staples (food, household products), utilities, and the like, where their businesses actually aren't performing particularly well, but have managed to hold onto valuations that are well ahead of where they were two or three years ago.

People ask us how we are going to try and pick the bottom. Our response is that we don't try to pick the bottom but just respond to the value in stocks, both in terms of what we want to buy and what we want to sell. We are buying stocks that we think have extraordinary valuations, and we'll wait for the recovery of their businesses to come. On the other side of that, where we see companies that we think are in problematic environments and have high valuations, we're shorting them.

JM: Am I right in asserting that, say three years out, it looks like a somewhat higher nominal growth world than the last cycle that allowed this amazing ebullience for things that could either grow or behave like a bond?

AC: I think we will most likely return to an environment which looks more like what it did a couple of decades ago, where we had reasonable valuations and investors could make money in companies that delivered on earnings. As we've already spoken about, China has an opportunity to recover, and Europe, under a different set of circumstances of dealing with their energy crisis, will also recover. The US economy will need to experience a slowdown first. Economic systems are incredibly robust and it will come back down to the real assets in the economy and what drives growth. In three-to-five years’ time, we will come out of these downturns, and companies that are trading on single-digit P/Es with earnings in line with expectations or better, should perform well and reward investors.

The full interview is available in audio format on The Journal page of the Platinum website.

Andrew Clifford is Chief Executive Officer and Co-Chief Investment Officer and Julian McCormack is an Investment Specialist (Retail) at Platinum Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. For more articles and papers by Platinum click here.

View Disclaimer: This information has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006, AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management (“Platinum”). While the information in this article has been prepared in good faith and with reasonable care, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, adequacy or reliability of any statements, estimates, opinions or other information contained in the articles, and to the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by any company of the Platinum Group or their directors, officers or employees for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Commentary reflects Platinum’s views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. Commentary may also contain forward looking statements. These forward-looking statements have been made based upon Platinum’s expectations and beliefs. No assurance is given that future developments will be in accordance with Platinum’s expectations. Actual outcomes could differ materially from those expected by Platinum. The information presented in this article is general information only and not intended to be financial product advice. It has not been prepared taking into account any particular investor’s or class of investors’ investment objectives, financial situation or needs, and should not be used as the basis for making investment, financial or other decisions. You should obtain professional advice prior to making any investment decision. You should also read the relevant product disclosure statement and target market determination before making any decision to invest, copies of which are available at www.platinum.com.au/Investing-with-Us/New-Investors.