If you were to look only at headline indices, you’d be forgiven for believing that we have been living through one of the longest bull-runs in history. In Australian dollar terms, the S&P/ASX200 price index is up 41% over the past 10 years, while the MSCI World and the S&P 500 have jumped 153% and 268% respectively.

But, if the world’s stock markets are doing so well, why do so many investors seem so anxious?

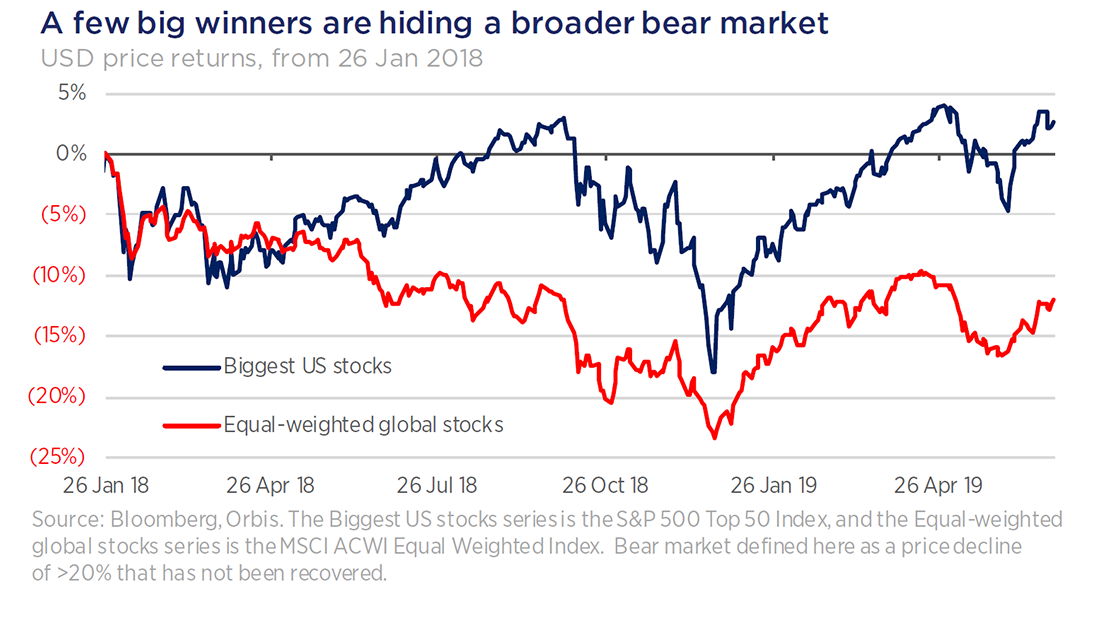

A few big stocks have driven returns

It turns out they have good reason. While the headline indices look good, it is only because of a few US mega stocks that have done exceptionally well over the period. If you look at an equal-weighted version of the index, instead of the more common market capitalisation-weighted index, the average stock globally has been mired in bear territory for over 18 months, while the top 50 US companies have done significantly better.

In order to understand this unhappy bull market and where it might be headed, we need to go back to 2009.

Gun shy in the wake of the GFC, many investors took a safety-first approach. They filled their portfolios with assets they could trust and, more importantly, understand. As a result, government bonds and bond proxies, blue chip shares with recognisable names and stable share prices did well.

As interest rates fell closer to zero, quantitative easing continued and growth remained elusive, so the fears engendered by the subprime explosion that started everything were replaced by new worries. What if growth never returns? What happens when central banks turn off the liquidity taps? What has happened to productivity? These worries helped to push bond prices even higher and the price of stocks that were perceived to be safe or that demonstrated any kind of fundamental growth higher still.

From 2016 came added uncertainty

And that was before 2016. Before Britain was divided by Brexit. Before the rise of populism in Europe and before Donald Trump began his mercurial presidency and led the US into a trade war with China.

Since then, the steady flow of money into what have traditionally been considered safe assets has turned into a flood. As the world has felt more uncertain, so the value of near-term certainty has skyrocketed. What had begun as a reaction to the recklessness of 2008 now borders on the ridiculous. And, there is no better example of this than the bond market.

Investors are now buying bonds at prices so high that they are guaranteed to make a loss if they hold the bond to maturity. More than US$17 trillion of bonds are trading at negative yields. Some of the buyers of these bonds are central banks, whose goal is to push down yields, and some are banks and life insurance companies who are compelled by regulatory or timing issues to do so.

But other buyers are just anxious, so uncertain about the future that they would rather make a small, guaranteed loss than put their money into something perceived to be more risky. Of course, for many the hope is that they will be able to sell the bond to an even more anxious buyer before it matures. That kind of thinking defeats the purpose of buying a bond in the first place – which is, the theory goes, the certainty that even in the worst case at least you get all of your money back.

Safety rather than fundamentals

This anxiety also permeates stock markets and has resulted in the unhappy bull market this story started with. The shares that have driven the index have been a mix of bond proxies with well-behaved share prices and those that have performed unusually well over the past four years.

In a world characterised by uncertainty these stocks have been comfortable to own and, as such, highly prized. Low volatility and momentum stocks trade at a 24% and a 47% premium to the broader market respectively.

Put another way, stable, established firms like Coca Cola trade at a Price to Earnings (P/E) ratio of 33 times, a level usually associated with fast-growing newcomers, while Netflix, for example, one of the stocks that has set the market alight in recent years now trades around a P/E ratio of over 100. Investors are willing to pay more than 100 times its current year’s earnings to own its shares.

And that is where the problem comes in. The criteria by which many investors are choosing stocks at the moment has everything to do with how comfortable it feels to own them and very little to do with the fundamentals of the businesses involved.

A P/E of 33 would be justified if Coke’s business was booming, for example, but it isn’t. While the drinks maker is still selling a huge number of soft drinks, its revenue line is stagnant and it is paying out all of its profits and piling on debt to meet its dividends. Likewise, while Netflix’s latest quarterly earnings report showed that it had grown revenue 26% year-on-year, justifiable questions can be asked about how likely it is that growth will continue at such a pace, especially with new players including Apple and Disney moving in on the streaming video action.

This is not the first time that markets have been driven by factors other than fundamentals, nor will it be the last. But it is important to acknowledge that it is happening. Currently, the market seems to be asking investors one question: How much are you willing to pay to feel safe? And the answer they appear to be giving is: a lot. Perhaps a better question to ask is: How much are you risking in your quest to feel comfortable?

Charles Dalziell is Investment Director at Orbis Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This report constitutes general advice only and not personal financial or investment advice. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or individual needs of any particular person.

For more articles and papers from Orbis, please click here.