Editor's Note: This article was first published by Franklin Templeton on 17 March 2023.

The commentariat until recently had shifted from hard to soft landing to no landing at all. Suddenly, those lags in monetary policy don’t look so long and variable after all. But it’s highly unlikely that we are about to face another banking crisis, GFC style. The tremors reverberating across the banking world from Silicon Valley to Zurich expose idiosyncratic weaknesses, but the risk is that markets focus on the headlines and miss the bigger issue building beneath the surface. Banks can be rescued in a heartbeat with unlimited liquidity from central banks…

*BANKS BORROW $164.8B FROM FED FACILITIES IN WEEK TO MARCH 15

The franchise and confidence in the institution might be irreparably damaged but liquidity crises can be solved with the flick of a switch per the headline above.

Credit constriction is the key issue

The real issue that lies behind the banking turmoil is the constriction of credit supply that central banks are inducing amidst their assault on inflation. The constriction of credit, and withdrawal of liquidity, ultimately finds out the weaknesses in the system. The supply of credit supports growth and drives inflation. Just as the excess creation of money through the pandemic caused inflation to surge, its rapid destruction as central banks shrink the money supply is highly disinflationary.

In a highly financialised world fuelled by liquidity and availability of credit, sooner or later things start to break when central banks withdraw that credit and liquidity as rapidly as they have. The only question has been what and when. The warning signs have been brewing for several months that monetary policy has been choking off the supply of money. This is the pointy end of the hiking process.

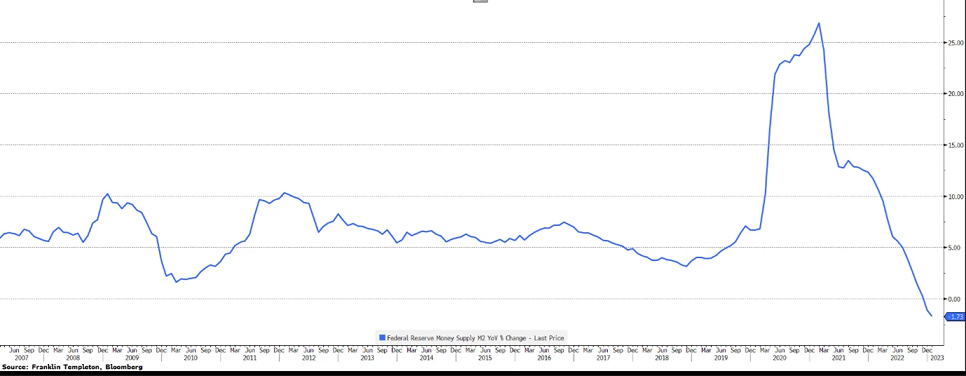

Consider the rate of growth of US money as measured by the M2 definition. It boomed in the pandemic of course and started shrinking toward the end of 2022.

Many may not have realised that the number of banks in the US insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp is nearly 5,000. These figures do not include credit unions which fall under separate regulation. There are around 6,500 of those. In Texas alone there are 375 banks. The rapid demise of smaller banks in the US and at Credit Suisse is a timely reminder that when the liquidity pool gets drained there is always going to be people standing naked.

But the tight credit conditions being inflicted on economies is the ultimate culprit. Arguably, the demise of Silicon Valley Bank owes its genesis to the dramatic shrinkage of capital being made available to the private equity, start-up and tech sectors which made up the bulk of SVB’s customer base. As credit has been drained from the system and liquidity become scarce, funding markets for start-up ventures has dried up. What do you do then? You draw on your liquid bank deposits. So, whilst we might finger point at idiosyncratic blow-ups, the fact is central banks have squeezed funding markets like the proverbial lemon making the cost and availability of credit that much more challenging.

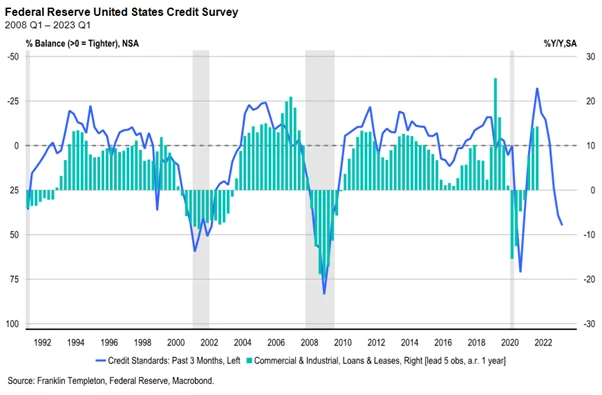

The fallout from credit tightening

Nowhere is the tightness of bank credit more closely scrutinised than in the benchmark New York Fed Senior Loan Officer Survey. Whenever it has signalled conditions as tight as currently indicated the US has been in or soon entered recession. The below chart highlights that commercial loan growth follows the survey with a lag. Note the survey is now a couple of months old and predates the bank mayhem of recent days. If there is one memo that regional bank treasurers are likely sending to their loan officers this week, it’s ‘don’t lend any money unless the credit is pristine and well-priced’. The provision of commercial loans dries up when the survey points to conditions this tight. No doubt the next survey will be a doozy.

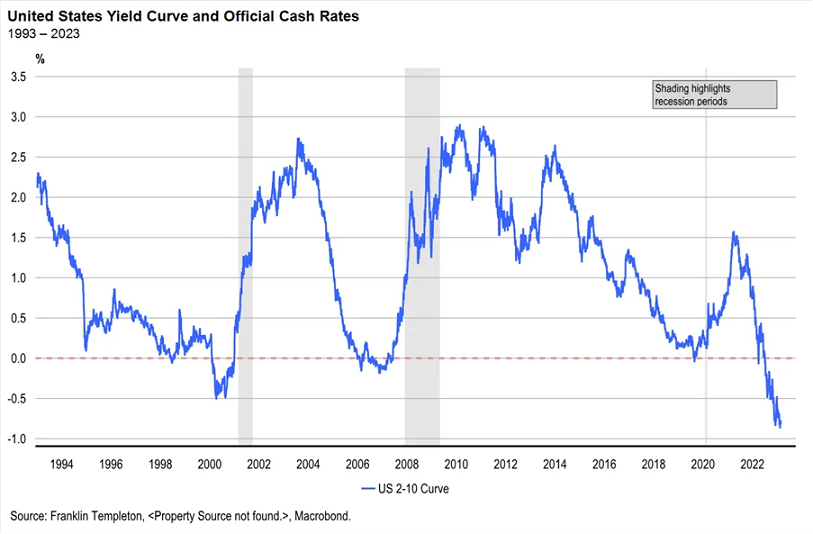

One reason why monetary policy is destroying the flow of credit is the extreme level of inversion of the yield curve in the US. It has until recently been at acute and record levels of inversion. For banks that borrow short and lend long this has been a recipe to stop creating credit or go broke. It’s not coincidental that the curve shape maps closely to the loan officers survey above.

None of this shows up in official CPI stats for a while, of course, despite this being largely the only thing central banks are focussed on. That’s because it leads, and points to a significant contraction in credit creation and GDP and inflation in the coming period, rather than the past.

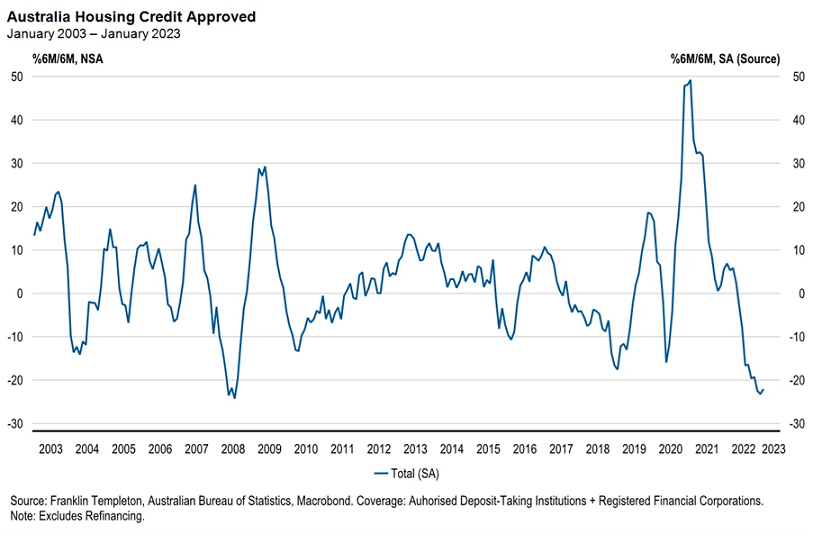

In Australia, the impact of tighter credit conditions at the hand of the RBA is centred on construction and building. More than 1200 firms in that sector have entered receivership, liquidation or administration this financial year so far. The chart below shows the 6 monthly change in new credit for housing. It’s never been weaker outside the GFC. This isn’t surprising, as no-one can afford to buy overpriced houses at current interest rates.

But tremors have been showing up for a while as the credit pool has been drained. The UK Pension system crashing the gilt market, FTX imploding or some banks looking shaky are in some ways distractions that are too easily dismissed as isolated events. Monetary policy is a blunt tool and it’s finding out the interest rate and liquidity sensitive areas in the market quickly.

Banking and capital markets run on confidence. If that confidence goes, it’s over.

Bond markets are ahead of the game

Central banks are singularly focussed on lagging CPI data whilst largely ignoring the forward-looking data on credit measures. The latter continue to signpost a significant slowdown underway. For the history buffs, it is Interesting that in June 2008 the Fed Meeting notes said:

“The Committee expects inflation to moderate later this year and next year. However, in light of the continued increases in the prices of energy and some other commodities and the elevated state of some indicators of inflation expectations, uncertainty about the inflation outlook remains high.” - FOMC June 2008.

Such a statement could easily be included in next weeks scheduled meeting. Of course, Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy in September 2008, Bear Stearns had already fallen over, and the housing market went up in flames. It’s likely that central bankers are a little more attuned to the financial stability risks these days.

This is unlikely another GFC. But it’s always something and flow of credit matters in a highly financialised world. In 2018, the Fed broke the High Yield bond market and was forced to back away when not a single company was able to raise money in that market in December of 2018. Many have said central banks can’t stop raising rates even amidst these ructions because of inflation. If credit and liquidity tighten as they have, inflation’s grave is dug. It may not have been filled in, but it’s over and just a matter of time. Central banks will be highly sensitive to signs that the financial system is quaking, and the flow of credit is stalling.

The bond market has decided that hikes are largely over, and cuts are coming. That is consistent with our view, and we have been positioned accordingly but it has been startling how quickly things shift. This isn’t a linear path and it’s likely we see heightened volatility in coming days and weeks reinforcing the importance of being nimble.

Andrew Canobi is a Director, Fixed Income; Joshua Rout, CFA, is a Portfolio Manager and Research Analyst, Fixed Income; and Chris Siniakov is Managing Director, Fixed Income at Franklin Templeton, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment or financial product advice. It does not consider the individual circumstances, objectives, financial situation, or needs of any individual.

For more articles and papers from Franklin Templeton and specialist investment managers, please click here.