Australia hasn’t had a recession for almost a quarter of a century, so are they a thing of the past? The word ‘recession’ connotes fear for those that have been through one, being less than half today’s workforce. The word ‘depression’ suggests terror for those that went through the last one in the 1930’s as a worker, being 31,000 Australians, or just 0.13% of the population.

A recession occurs when we have two or more quarters of negative economic growth, usually converting to a negative year overall. A depression occurs when we have two or more negative years, usually four in a row for Australia.

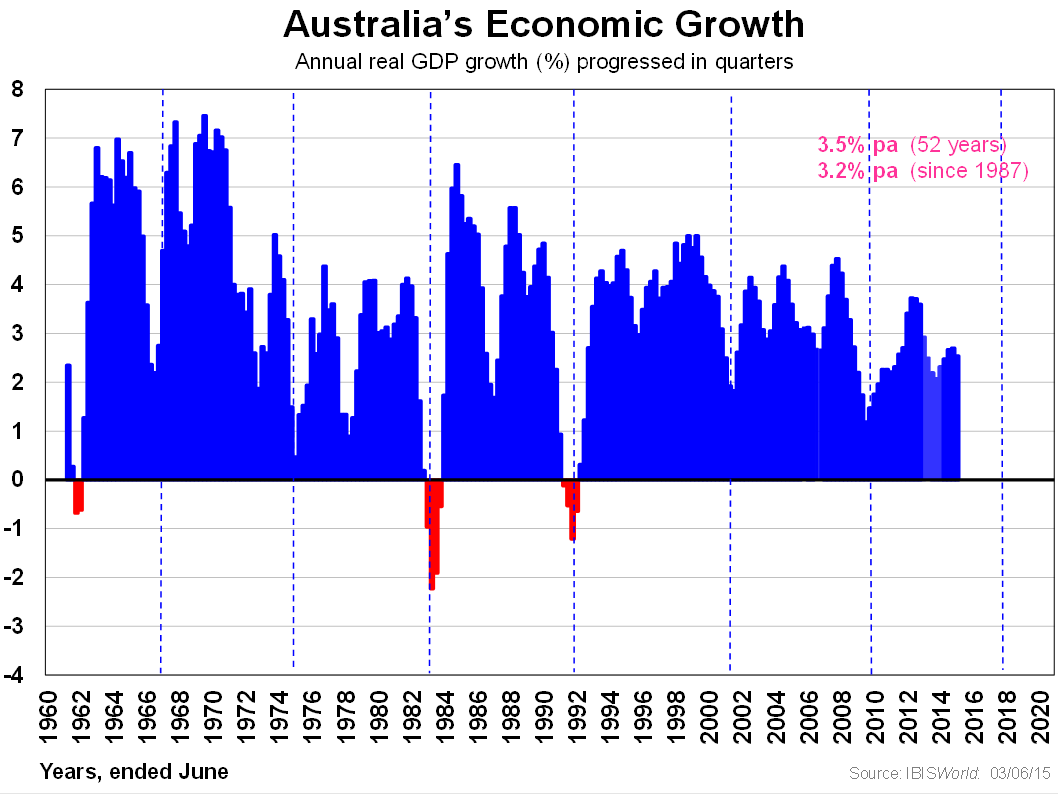

Fortunately, we have had only four depressions in 227 years, the last one ending over 80 years ago in the 1930s. And we have fewer recessions than in the Industrial Age - when we had 20 of them over a 100 year period or one every five years on average - but only two over the past 50 years since the new Infotronics Age began in 1965. The last one was 23 years ago, ending in 1992 as shown in the exhibit. We return to the prospects of another one shortly.

Avoiding complacency setting in

Half today’s workforce of 11.8 million has never experienced a recession in their working lifetime. It carries the risk of the boiling-frog syndrome whereby complacency sets in, productivity growth slows, deficit spending becomes a habit, workplace reforms are put off, and unemployment rises. This is Australia today, and Greece is an extreme example over a much longer period: two generations at least, and now a classic basket-case, as they say.

Strangely, we may be better to have another one sooner rather than later to correct the above drift, notwithstanding we have a very low national debt and a relatively modern economy.

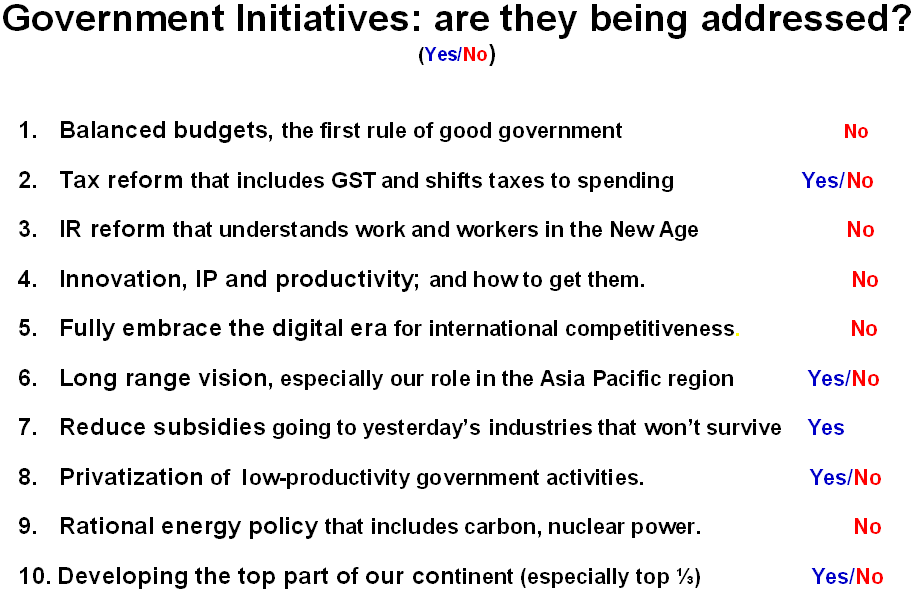

A lot of things need to be done, as the list below suggests. There are not enough ‘yesses’.

The nation has had reform paralysis for much too long, and that is dangerous given our new economic and social homeland of Asia: the biggest, most dynamic and fastest growing region of the world, where we will be trading and competing for a century or more.

We need workplace reform, involving penalty rates, contractualism (to reward on outputs not inputs), more worker freedom and flexibility.

We need reform: in our parliament (Senate election protocols); in our Federal budgeting (the deficit habit); in our taxes (GST in particular); in our negative productivity in government-owned activities (22% of the nation’s GDP); in our society (more fairness, but also more self-reliance); in our energy policy area, and more.

However, while all these issues are important to our rising standard of living - indeed critical over the longer term - the cause of recessions lies elsewhere.

Potential causes of recession

Markets pull the economy (GDP) along, not production. There are three major sectors in the marketplace:

- overseas expenditure (our exports)

- consumption expenditure (households and government on our behalf)

- capital expenditure.

Exports do go negative in growth but rarely, and even those occasions have not been severe enough to trigger a recession over the past 50 years.

Consumption expenditure has not gone negative since World War II, so has never caused a recession in the lifetime of most Australians unless they are well over 75 years of age. One of the factors that has helped keep consumer spending in the positive zone is the dominance of services in household spending. Goods once consumed over two-thirds of household budgets a century ago. Now, only a fifth is due to manufacturing productivity and - more recently - cheaper imports.

Indeed, in 2013, household spending on outsourced chores and services exceeded retail goods spending for the first time in history. Consumers are less likely to stop or curtail spending on services than goods, especially durables. They will still pay for electricity, insurance, health, education and even entertainment of one form or another. The facts show this to be true over the past six or more decades.

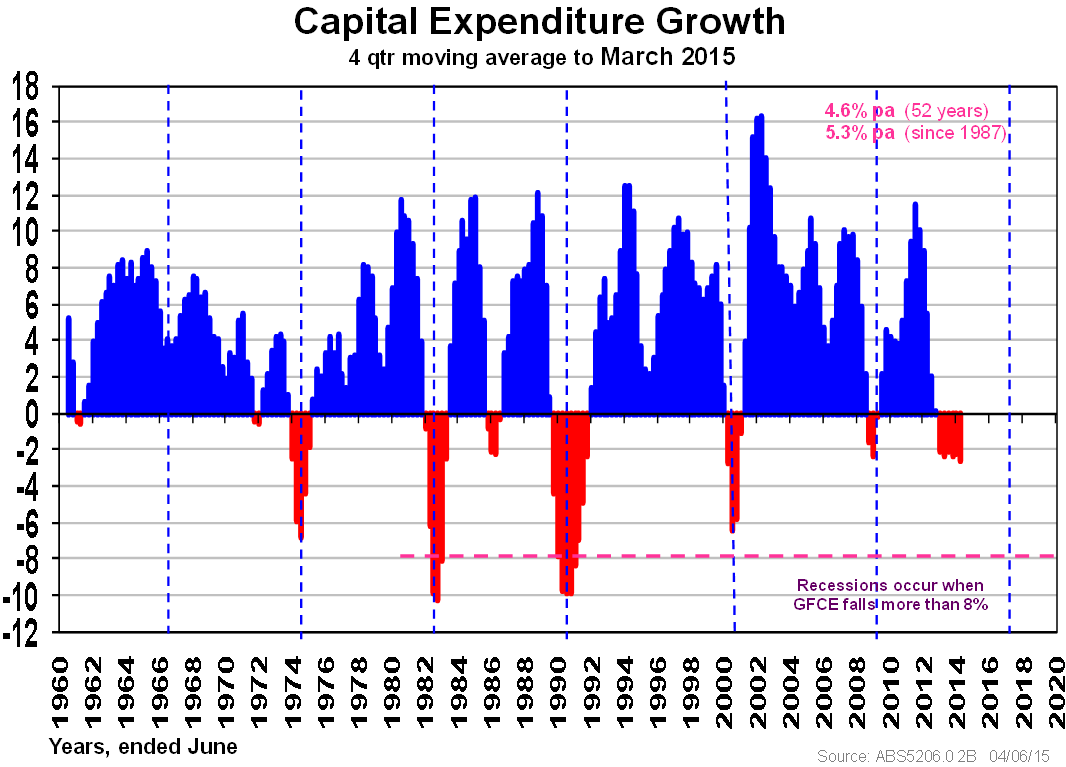

That leaves the only market sector that can cause recessions: capital expenditure. The two recessions we have had in this new age were caused by a collapse of more than 8% in a given year. This happened in the 1982-83 and 1991-92 recessions, as seen in the following exhibit.

Dotted lines are shown around every 8½ years on average. This is what economists term the long business cycle. It is at the end of each of these periods when our economy is susceptible or vulnerable to a collapse in capital expenditure. It was in 2000-01, but averted by the Howard/Costello initiative in housing construction with the First Home Buyers Grant, doubled in the following year to make sure a recession was averted! We missed a recession in 2008-09 too, due to the massive backlog of mining capital expenditure.

The Rudd initiative of pink batts and give-away money in two tranches to households was not necessary, and a panic reaction. We didn’t need any bolstering of consumer spending. Mortgage rates had collapsed from 9.25% to 5.25% from 2008 and petrol price rises had fallen sharply, enough to free up over $10,000 in after-tax money for the majority of households! Better to suggest they spend some of it rather than give them more, and at the same time let the public know we were not going to experience a GFC as we had no national debt.

But the looming risk of a recession in 2017-18 at the end of the current long business cycle is very real this time. Over 25% of our capital expenditure (itself 28% of GDP) was going to the mining boom until recently. At least half of this or more will have gone by 2018, so filling that hole is the challenge in avoiding a recession. Governments are largely aware of this risk, hence the drive into more infrastructure spending.

We have a couple of years to fill this hole, otherwise a probable recession is in train. But in the absence of serious reform vision, initiatives and courage, it may not be a bad thing if we had one to shake us out of lethargy. Another one ‘we had to have’, so to speak.

Phil Ruthven is Chairman, IBISWorld and Australia’s leading futurist.